On 10 February, the Lunar New Year officially begins, marking the start of the new year in many Asian countries, including China. We enter the year of the dragon, to be precise, the ‘green wooden dragon’ (not to be confused with the fire dragon that will dominate in 2036). We are not experts on the Chinese zodiac (and generally don’t rely on it to manage portfolios), but from what we understand, the dragon symbolises not only freedom but also prosperity and awakening. Could this be a good omen for the Chinese economy, which for over two years has been facing a slowdown that is undermining the perception of Beijing’s health?

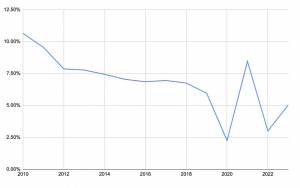

China’s GDP grew by 5.3% last year, a level unattainable for most Western countries, but it denotes a significant decline compared to pre-Covid levels and continues a trend of economic slowdown. Beneath the surface, numerous crises have erupted, such as those affecting the real estate and banking sectors, a local government crisis, a slowdown in domestic demand and deflationary pressures. Economic performance has translated into extremely disappointing performance in financial markets as well, with the CSI 300 index losing over 11% in 2023.

Annual GDP Growth in China. Data illustrated by Moneyfarm based on World Bank data.

Although a slowdown in growth levels is considered natural, economic issues are taken very seriously by Beijing, as there is fear that the emerging problems may undermine China’s medium-term growth path. Until recently, Beijing was considered the hub of the global economy and today risks becoming seriously ill. It’s a crisis of perception for a country trying to extend its geopolitical influence over half the globe.

The narrative is changing rapidly. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and others define China as a “brake” on global growth. And the government’s official growth targets for next year, around 5%, are met with scepticism. Recently, Moody’s changed the outlook for Chinese debt (A1 rating) from stable to negative. The result immediately sparked a media campaign in China aimed at discrediting the agency’s credibility. In short, it seems that a growing gap is forming between the government’s attempts to maintain a successful narrative and the evaluation of the country by markets and international organisations. At the centre is an objective framework in which increasingly evident systemic problems emerge for a $19 trillion economy called upon by its size and vocations to complete the path towards the status of an advanced economic superpower.

What is frightening is the possibility that the decline may be structural. In the decade leading up to 2021, China experienced one of the fastest global economic growth rates, averaging 6.7% annually. Now the IMF forecasts a gradual decline in China’s growth rate, down to 3.5% by 2028, citing challenges such as productivity weakness and an ageing population.

But what are the reasons for this slowdown? What we are witnessing today is likely a structural response to the end of an unprecedented expansion of credit and investments in the last decade. In response to the global crisis of 2008 and 2009, President Hu Jintao’s government injected liquidity and investments into the economy. The subsequent administration led by Xi Jinping did not curb borrowing, which, while fostering the growth of national champions in innovative sectors such as advanced industry and technology, ended up disproportionately inflating less productive sectors like real estate.

The Chinese financial system now finds itself unable to maintain the same levels of credit growth as in previous years, undermining Beijing’s control over the economy. Moreover, the government’s attempt to limit borrowing to protect financial stability has eroded confidence at a time when the economy was already not doing too well.

In addition to this, there is the issue of suboptimal pandemic management. The rigorous zero-Covid policy, with severe restrictions and impact on private enterprise, has hit the most vital parts of the economy. This has resulted in weak domestic demand, fuelling fears of a deflationary spiral. China faces increasing downward pressure on prices, a problem opposite to that faced by Western governments. The risk of a deflationary spiral could lead to reduced production, wage decreases and increased unemployment. Stagnation in productivity, politicisation of regulation, an ageing demographic, youth unemployment and economic disparities complete the full set of challenges.

Looking ahead, the challenges that the Beijing government must address to revive growth are numerous. The real estate crisis is perhaps the largest obstacle. The collapse in home sales has disrupted the business models of some of the major developers, who have faced liquidity crises and often outright insolvencies. The crisis has spread to the banking sector, causing further insolvencies and widespread protests. As a result, local governments, burdened by Covid-related expenses and declining land sales, are struggling to finance themselves.

The response to weak demand and declining confidence will necessarily have to come from the government. We believe that the approach to fiscal and monetary policy in 2024 will be the decisive factor. The Central Economic Conference has outlined a roadmap of priorities, focusing on scientific innovation, robust domestic demand, stability, rural development and ecological investments.

On one hand, the fact that the solution is in the hands of the government conveys a certain reassurance, given the material capabilities and the Communist Party’s willingness to change course. On the other hand, the scenario still reflects an economy characterised by a private sector not entirely capable of standing on its own two feet. Moreover, Chinese industrial policies, loaded with industrial funds, state subsidies and privileged access to foreign technologies, have created problems of overcapacity in key sectors. An example of this is the growth of ‘green’ sectors that are attracting a lot of public and private resources, raising eyebrows in Washington and Brussels. Throughout China, new factories are emerging that produce electric vehicles (EVs), batteries and other essential products for energy transition. However, with a saturated manufacturing sector and domestic consumption nearing historic lows, Beijing will necessarily have to turn to foreign markets to absorb this production, risking further strained trade relations with other economies that are also promoting domestic industries and the jobs that produce many of those same products.

In short, on one hand, the government’s arbitrary intervention will have the difficult task of avoiding creating a more inefficient economy; on the other hand, today it seems to be the only viable solution to revitalise domestic demand. Excessive focus on growth rather than structural reforms, however, could exacerbate existing imbalances: reducing the government’s role in economic affairs is necessary to restore private sector confidence and stimulate investments, but currently, it is also the main lever that China can use to emerge from the crisis.

Moreover, in this uncertain economic situation, compounded by international crises, foreign investments in China are plummeting, down by 19.5% in December. Although a minority portion of all investments, this data shows lingering doubts about the attractiveness of the Chinese business environment, the same doubts that have also undermined the value of investments in recent years. We believe there is a risk that this trend will continue, despite the Chinese government’s direct interventions to support the markets, a recent development indicating the government’s concern that negative performances could undermine financial stability through structured products.

China now needs to demonstrate that it has built an economy capable of standing on its own two feet. The game is on, but political choices will determine whether China can overcome these challenges and regain its status as the engine of the global economy, striving to balance centralised growth support with forward-looking structural reforms capable of creating an economic environment that can thrive beyond public support. Only then will the dragon continue to soar.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.