This week we’ve seen contrasting moves from the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England. In the US, the central bank cut interest rates by 0.25%, while in the UK the Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee voted to leave its policy rate unchanged.

Both these decisions were largely expected by investors. While both the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England are notionally independent, the administration in the US has forcefully argued that policy rates should come down. And the most recent nominee to the US central bank, confirmed this week, voted for a 0.5% cut to the policy rate.

We’ll dig into the data in a bit more detail, but in each country, we think central bankers face some nuanced choices. Inflation is above target in both countries, particularly in the UK. Underlying demand in the US remains pretty solid, even if the labour market is softening. Growth in the UK remains pretty muted, and unemployment is drifting higher, but headline inflation seems pretty stubborn for now.

All that said, we think that the Federal Reserve will cut rates again, probably twice, before the end of the year – even with inflation approaching 3%. After that, however, we think that many of the current voting members will find it tough to vote for further cuts, barring a notable shift in the underlying macro and inflation backdrop. UK central bankers probably have the trickier hand to play – with higher inflation and slower growth. We think we’ll need to see signs of slower inflation in the coming months for the UK central bankers to feel comfortable cutting rates further.

What data tell us

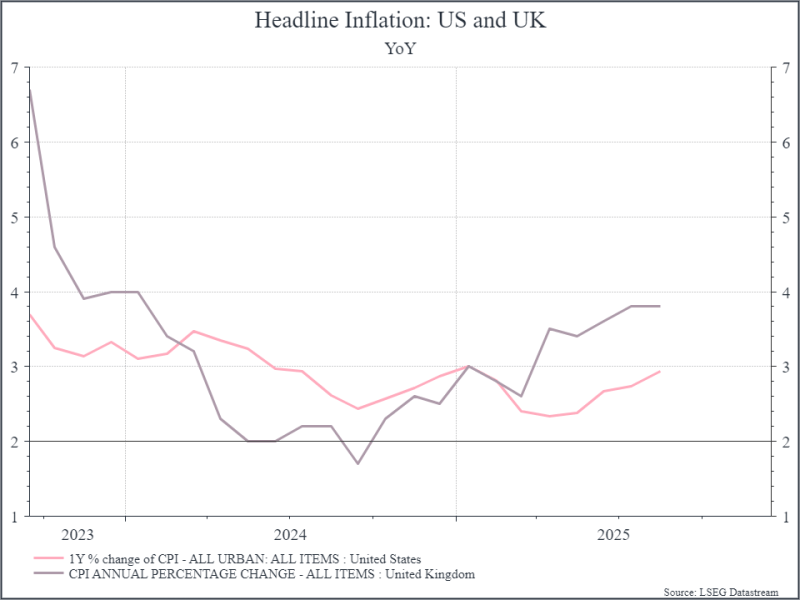

Let’s dig into the data a bit more. The chart below shows annual inflation in the US and the UK. Consumer prices are rising faster than central bankers would probably like, but the situation is more challenging in the UK than the US. Some of the faster inflation in the UK may reflect utility price increases, but the underlying picture isn’t great. It helps to explain why the Bank of England has left rates unchanged this week and why the prospects for future rate cuts are quite limited.

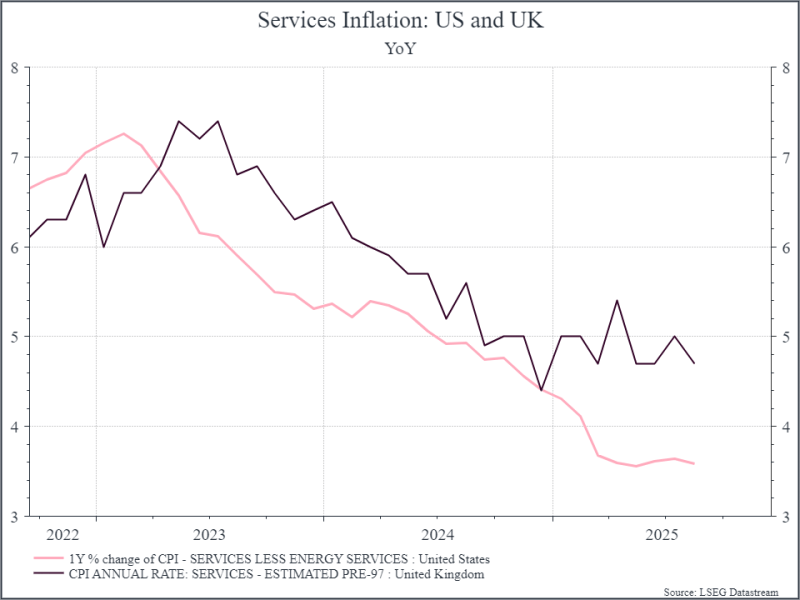

The second point is around tariffs. There’s been a lot of debate about the impact of tariffs on consumer prices. In general, we’d argue that the impact of tariffs on inflation, particularly in the US, has been more muted than we might have feared back in April. It might be a question of time, and we could see inflation pick up in the coming months. The chart above would suggest that annual inflation in both the UK and the US has been picking up in recent months. Even there, a number of central bankers argue that any such inflation will be a one-off and shouldn’t be considered when it comes to interest rate policies. But the other point is that tariffs really impact goods inflation. In theory, price increases in services shouldn’t be affected. And we can see that services inflation continues to run well above headline inflation, as the chart below shows.

So, if we were just looking at inflation data today, we’d argue that the case for cutting policy rates doesn’t look particularly strong. But inflation isn’t the only variable. The labour market is a key variable when central bankers think about policy rates, particularly in the US where the Federal Reserve has a specific mandate to focus on employment.

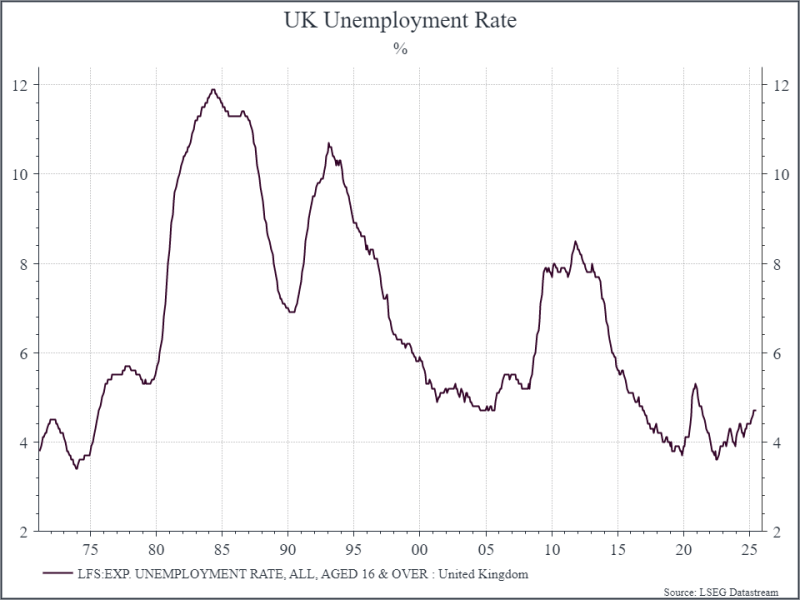

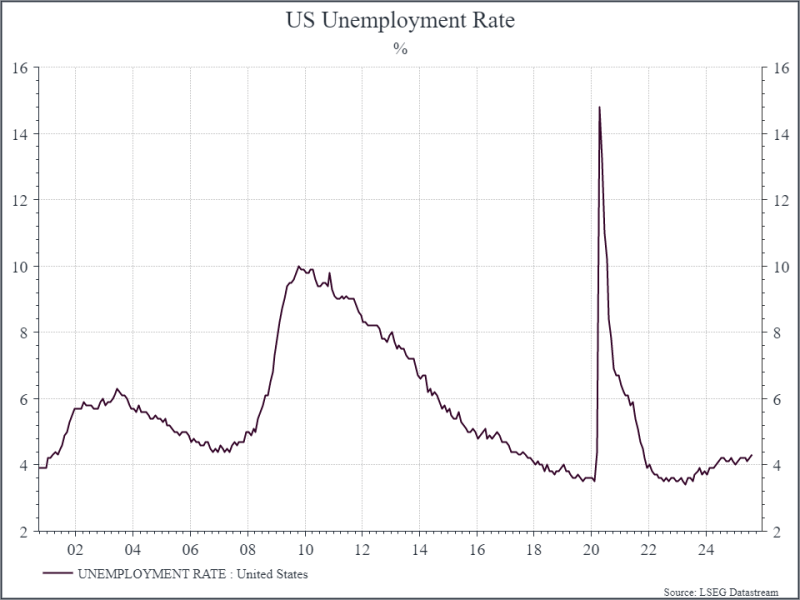

Looking at headline unemployment, we can see that in both the US and the UK, the unemployment rate is fairly low compared to history, but is drifting higher. If anything, the UK unemployment rate is moving faster than is the case in the US.

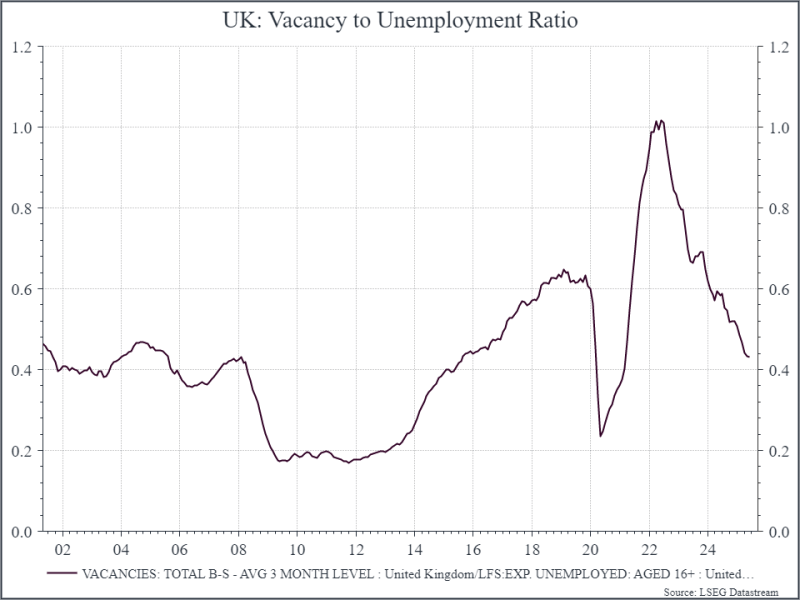

Other metrics paint a similar picture. The chart below shows a steady decline in the ratio of total in the UK relative to the number of unemployed. The US shows a similar trend, albeit the absolute figure is some way higher.

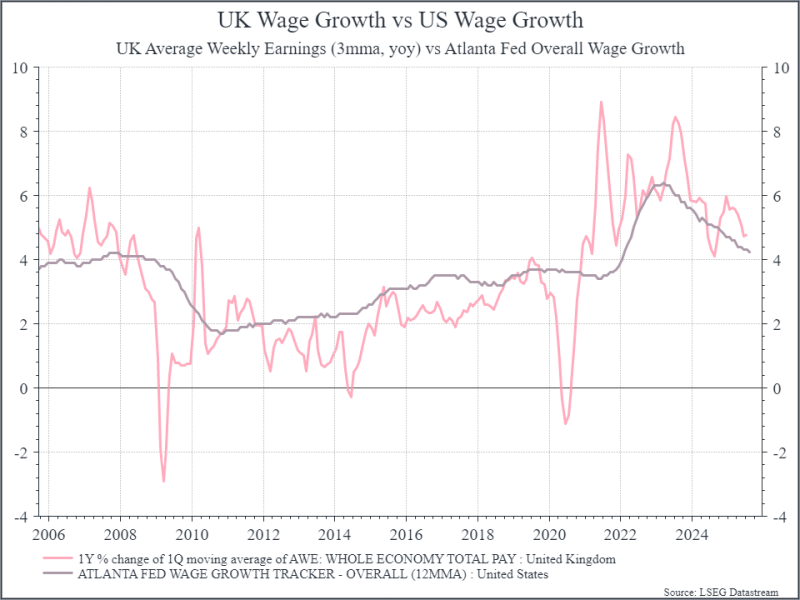

Looking at wages across the two countries, we can see that wage growth remains pretty robust – still above 4% year on year. Workers continue to regain some of the purchasing power they lost following the inflation spike in 2022. That’s good news for households, but a more mixed message for central bankers trying to get annual inflation back towards 2%.

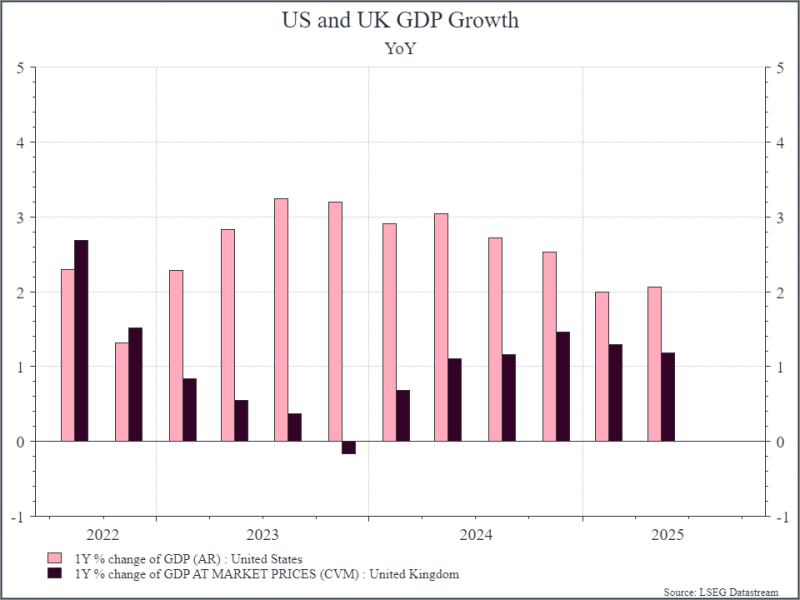

Finally, there’s other macro data to consider. The chart below shows annual GDP growth by quarter for the US and the UK. We can see that the growth in the US has outperformed the UK since the end of 2022. More recently, strong retail sales growth in the US, in data released this week, highlights that underlying consumer demand remains decent, even if the labour market has slowed.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.