The tense and tragic geopolitical situation caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is ongoing and there is no clear end in sight. Over the past few weeks, the West imposed yet more economic sanctions to discourage the continuation of the unprovoked aggression.

These are highly damaging to the Russian economy and are perhaps contributing to peace negotiations that are reportedly underway. The impact is such that several rating agencies have downgraded Moscow’s debt to “junk”. Russia, along with Belarus, is in a difficult economic and financial situation as a result, with both just one step away from default.

In this article, we will discuss the various economic and financial ramifications of these sanctions, to try and build a comprehensive picture of the situation.

The sanctions imposed on Russia

On February 24, Russia began its invasion of Ukraine. Western countries responded quickly by imposing their first tranche of sanctions, which targeted:

- The financial sector

- The energy and transport sectors

- Dual-use goods

- Export control and financing

- Visa policy

This first round of sanctions, it seems, barely made Putin flinch. So, after a few days, additional countermeasures were rolled out. These included a ban on interaction with the Russian Central Bank, a €500 million support package to finance the shipment of equipment and supplies to the Ukrainian armed forces, a ban on flying in EU airspace and access to Union airports by Russian carriers, as well as fresh sanctions for 26 other Russian individuals.

Then came the exclusion of Russian banks from Swift. Seven leading Russian banks from the international financial network, thus compromising the ability of the banks to operate worldwide. The sanctions didn’t end there, either. New investment in the Russian energy sector has been banned and extensive restrictions have been introduced on the exporting of equipment, technology and services in the energy industry.

Beyond the economic consequences, are sanctions a useful deterrent? Could they bring Putin to the table for peace talks? These are important questions. When these decisions are made, the potential costs and benefits are carefully weighed up. After all, sanctions also come with a price for the states that impose them.

In theory, sanctions are an effective tool. They allow countries to exert pressure while avoiding military conflict. In some cases, sanctions have led to positive results. In others, they’ve failed to have any discernible impact on their stated aims. When they fail, the reason tends to be inaccuracy and frequency. Often, the US (and, more generally, the West), uses sanctions in a broad, sweeping manner, without due consideration for what they’re targeting.

The current sanctions imposed on Russia are certainly strong and are sending the country’s economy into crisis. Suffice to say that, by April, the country could risk defaulting on its government debt if it fails to pay foreign investors. However, whether they manage to bring Putin to the negotiating table is still to be seen.

Is Russia in danger of default?

Before we answer this question we should say that, until a few weeks ago, Russian government bonds were generally not considered a particularly risky investment. The country has relatively low debt and large reserves of liquidity.

With more than $640 billion in gold and foreign exchange reserves, the debt was virtually guaranteed. However, the situation has changed radically. Following the sanctions, the risk of default for Russia is becoming increasingly real.

Fitch, Moody’s and S&P have all slashed Russia’s debt rating. The World Bank described Russia and Belarus as being squarely in ‘default territory’. Russia’s economic downturn could take a few more days yet, and the full extent of its issues are yet to be seen.

If Russia fails to meet the deadlines set for April then the country may financially run out of road. So, what would happen next? Usually, when a country defaults, the worst consequence it can suffer is exclusion from international markets.

If you are unable to pay your debts, it becomes difficult to find creditors; therefore, you risk a complete financial meltdown. The problem here is that Russia has already lost access to international markets. It cannot ask for money from eight of the world’s 10 largest economies and investors are unwilling to invest in the country. To put it lightly, these are worrying signs for the Russian economy.

As for the consequences of a Russian default, it seems unlikely that it would have any significant financial ramifications. There may be some European financial firms affected but any ripple effect is likely to be limited. It’s also possible that governments could intervene to support any companies or sectors particularly affected by the Russian economic meltdown.

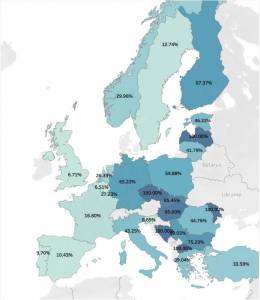

European dependence on Russian gas and the road to energy independence

European dependence on Russian gas varies wildly from country to country. Sweden, for example, has minimal dependence on Moscow, while Hungary is completely dependent on Russian gas. All EU member states have at least some link to Russian gas. In fact, about 30% of the gas imported by the EU currently comes from Moscow.

Although the EU has attempted to diversify its energy sources over the years, the link with Russia has remained strong. The key factor is geography. Structurally, it is much easier and cheaper to transport gas from Russia by pipe than it is to get it from elsewhere.

Russia’s attack on Ukraine represents a watershed moment for the EU, which is working to make itself as independent as possible from Moscow in the future. Green energy projects are about more than environmental protection – they also have the express purpose of freeing the West from dependence on Russian energy.

The EU has set out an ambitious strategy that follows two paths, one short term and the other long term. In the immediate future, the goal is to diversify the gas supply as much as possible and exploit the full potential of green and low-carbon energy sources. In the short term, greater diversification will be achieved through a wider supply of LNG, shipped from countries like the US and Qatar.

In the long term, the EU aims to increase the amount of alternative gas used, such as biogas and hydrogen – the production of some 35 billion cubic meters of biogas by 2030 has been targeted. Then there’s the whole question of clean energy. If the EU were to fully implement its climate projects for 2030, it would be able to reduce dependence on Russian gas by 23% by the end of the decade.

How we’ve responded

To improve the resilience of our investments and to keep volatility within our targets, we recently decided to rebalance our portfolios. The focus was on risk management and was achieved through two channels. Firstly, we increased our exposure to diversifiers (like commodities or the US Dollar). Secondly, we reduced our exposure to risky assets.

It is important to underline the fact that, when we modify portfolios, in addition to considering risk management needs, we also analyse the long-term prospects of the various asset classes. In this sense, this rebalancing aimed to better position portfolios for a broad range of different scenarios.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.