Finally, the Chancellor announced the latest government Budget. The process had gone on for so long that any announcement might have come as a bit of a relief, regardless of what it contained. It’s a good moment to take a step back and consider the Budget and what it could mean for portfolios.

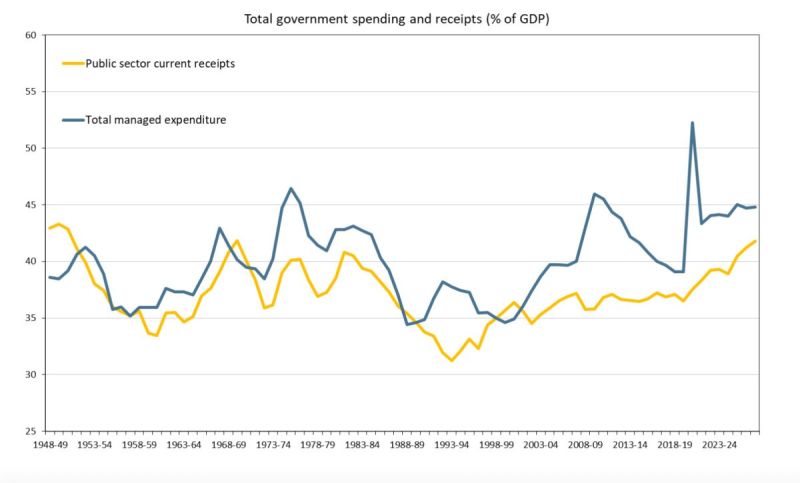

The UK, in common with much of the developed world, faces a bunch of fiscal challenges. The government’s role in the economy is quite large: the chart shows how UK government spending and revenues have evolved as a share of GDP since the 1940s. Expenditure (blue) has almost always run ahead of revenues (yellow), widening sharply during major crises. Both lines are now at levels that are high compared with most of the past forty years, and the recent trend suggests they are likely to move higher rather than lower in the years ahead.

At the same time, we also know that the tax base is pretty narrow. According to a House of Commons report from August 2025, the top 1% of taxpayers earn 13% of total income and pay close to 29% of income tax.

Across the developed world, demographics represent a challenge. Aging populations and an increasingly hostile stance on immigration raise questions about how governments will afford to provide services to their citizens.

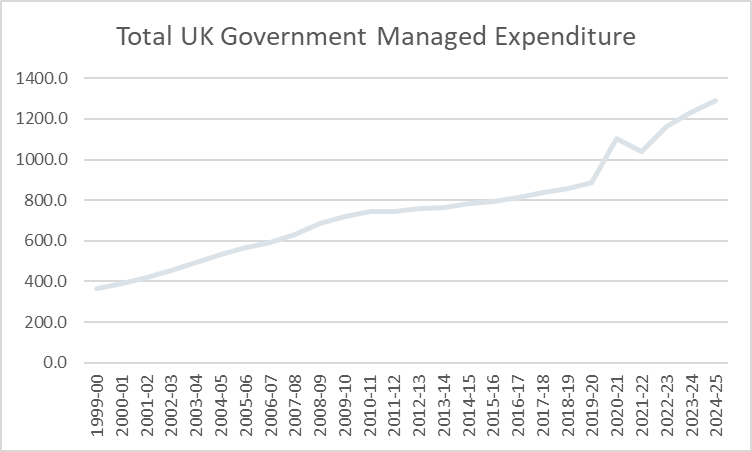

Cutting government spending is no easy task. The chart below shows total managed spending for the UK government from 1999 to 2025 (in billions of pounds), essentially the government’s overall annual spending across all departments. It shows a pretty steady increase in nominal terms during the period.

Even during the period of “austerity” between 2010 and 2019, total government spending continued to grow in nominal terms, albeit at a slower pace. It also rose slightly during that period when adjusted for inflation.

If David Cameron and George Osborne – the Conservative Prime Minister and Chancellor who pursued the UK’s post-financial-crisis austerity programme – couldn’t bring total government spending down after the Global Financial Crisis, it’s hard to imagine that Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves will be willing or able to do so before the next election.

That brings us to economic growth. The Chancellor has rightly highlighted that growth is the best, maybe the only, way to square this circle and generate enough tax revenues to finance the governments long-term spending plans. Unfortunately, accelerating economic growth through policy choices isn’t easy – or everyone would do it.

Enough of all that – what about the Budget? Without rehashing the details, the Chancellor probably did enough in the short term – raising spending sufficiently to reassure Labour MPs, and taxes enough to placate bond investors, at least for now. The timing is mismatched: spending appears immediately, while most of the tax increases only begin to take effect in 2027 and 2028. This limits the immediate outrage of taxpayers but still keeps the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) onside, since it is more focused on 2030/31. Overall debt to GDP is forecast to stay more or less flat during the period.

None of this really addresses the long-term challenges outlined above. There wasn’t much here to encourage economic growth. Tinkering with Venture Capital Trusts (VCTs) and the Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS), both tax-relief schemes for investing in small businesses, likely won’t move the needle.

The choice of tax increases was really driven by the need to not renege on manifesto promises rather than any rigorous analysis of the most effective way to improve the fiscal accounts. So, the Chancellor has firmly kicked the can down the road, but without causing any immediate wobbles in government bond yields. Given all of the noise over the past few months, that probably constitutes a win. But the UK, along with many of its peers, faces long-term fiscal challenges and we didn’t hear too much about that this week. Maybe next year.

In terms of portfolio positioning, we continue to think that UK yields look attractive for domestic investors. We remain biased towards shorter-dated bonds, given the long-term challenges that we’ve highlighted.

But in this case, stronger economic growth would likely be a benefit for investors in bonds as well as equities – and that’s still proving elusive.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.