Whether AI is becoming a ‘bubble’ has been a central topic for investors in recent months. We don’t believe we’re at that stage, but there are some warning signs we’ll continue to monitor.

What is a bubble?

The standard answer is that it’s a period where asset prices (for stocks, houses etc) rises far above some idea of intrinsic value. That’s fine as far as it goes, but it’s not always practically useful. After all, what is intrinsic value – particularly for assets like stocks that typically embed some expectations about the future?

If we look back at past periods which have been described as bubbles, we may see some common characteristics. A new technology emerges that has the potential for significant change. Investors and businesses get very excited. They try to predict who are the likely winners – both companies and sectors – and allocate capital to those sectors. Hopes for the impact of the new technology continue to rise and more capital floods into the sector. Valuations and expectations continue to rise. Eventually, some sense of disappointment – or reality – kicks in, often because too much money is chasing too little opportunity. Expectations deflate, asset prices fall, some businesses and investments disappear and the “bubble” has deflated.

Periods typically considered bubbles include: 19th century US railroads, where excitement around a transformative new infrastructure led to overbuilding and financial failures; the telecom and fibre boom of the 1990s, driven by expectations of an immediate surge in data usage, which prompted companies to invest too much, too quickly; and the late-1990s internet boom, when “dot-com” companies were valued on future promises rather than current profits.

Looking at these examples, it’s important to note that a “bubble” doesn’t mean the underlying technology failed or was irrelevant. Rather, expectations – especially about the scale and, crucially, the timing of adoption – proved too optimistic.

AI expectations and equity markets

There’s certainly a lot of hype around Artificial Intelligence: it dominates investment debate and news articles. Investors and policy makers hope that AI will help raise productivity and drive prosperity and economic growth. The amount of capital being allocated sounds enormous, raising questions about how those investments will be paid for.

One estimate sees capital spending on AI data centres reaching $3 trillion between 2025 and 2029. Spending on new datacentres to support Artificial Intelligence even shows up in the macroeconomic data, clearly supporting US economic growth. ChatGPT, an AI chatbot, currently has 800 million weekly users, according to its CEO Sam Altman, and that figure has been doubling every eight months. AI strategies are being defined and implemented in boardrooms around the world. Shares in companies that benefit from the AI boom – notably chip designer Nvidia – have rallied sharply over the past few years.

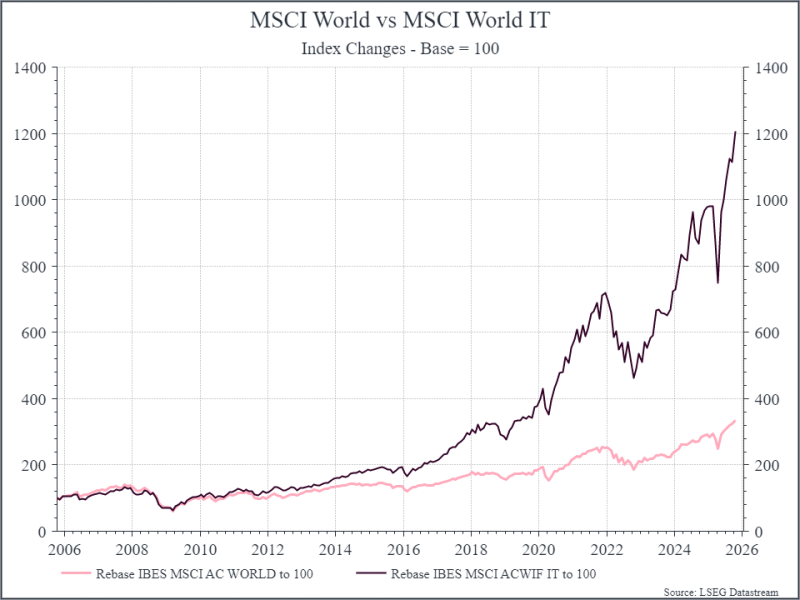

All those expectations are being reflected in equity markets. The chart below shows the sharp outperformance of global tech (the dark line) compared with global equities over the past decade.

A separate way to look at investor expectations is through valuations.

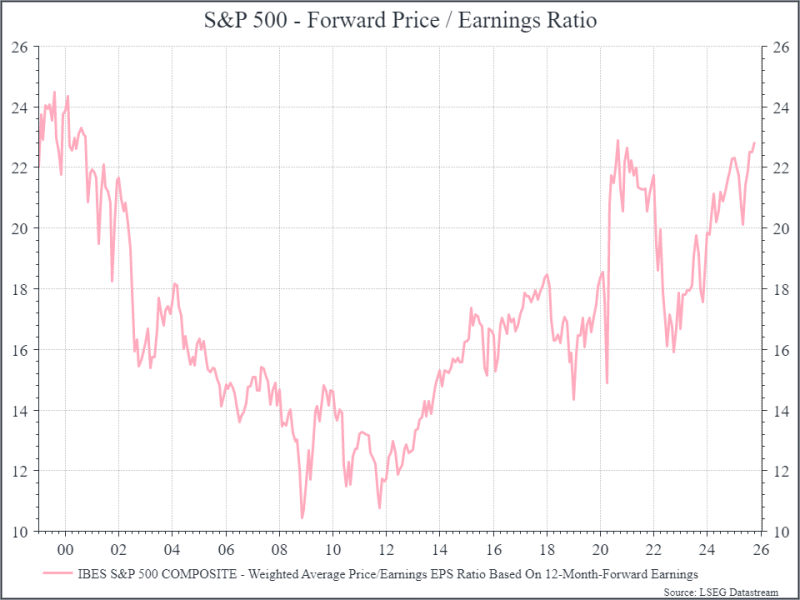

The chart below shows the forward Price/Earnings (P/E) ratio for the S&P 500 over the past thirty years. This metric compares today’s share prices with the profits analysts expect companies to generate over the next 12 months. A higher forward P/E suggests that investors are willing to pay more now for future earnings, implying strong confidence in growth.

On this basis, the US equity market is approaching the valuation levels seen in 2021 and in the 1999–2000 period. At the very least, it suggests that equity investors are optimistic about the future.

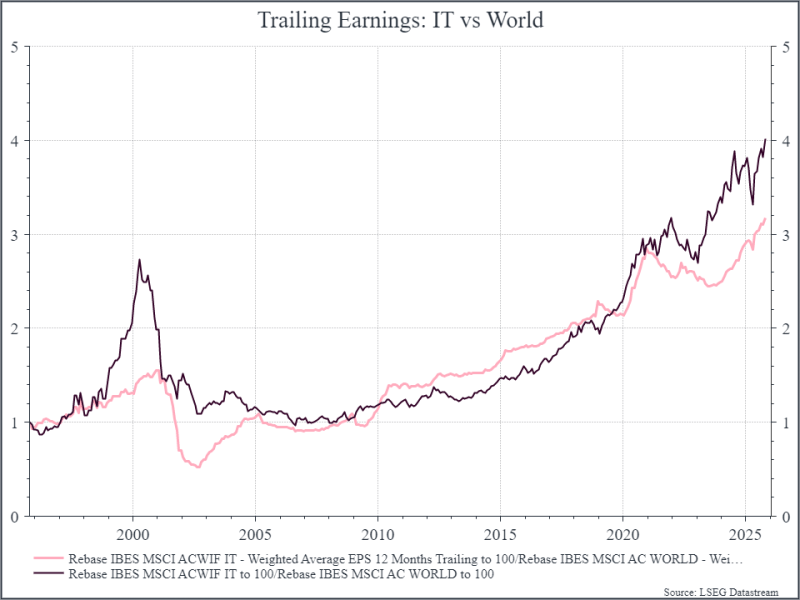

But does that qualify as a bubble? Let’s look at the chart below. It compares the global tech sector and global equities. Global tech is more than just AI, but the large listed US technology companies are well represented. The dark line shows the relative valuation of global tech, dominated by US tech companies, and global equities. The light line compares the trailing earnings for global tech and global equities.

We can see that over time, the relative valuation of global tech – that is, how expensive the sector is compared with the wider equity market – has risen as the tech earnings have grown faster than the rest of the world.

That wasn’t the case during the internet boom in 1999 and 2000. As the chart above shows, investor optimism in global tech wasn’t reflected in rising earnings – it was largely built on the hopes and dreams that only came to fruition in the following two decades. We should note that on this chart at least, the two lines have begun to diverge, maybe reflecting greater optimism about future earnings for global tech.

Tech: high and rising

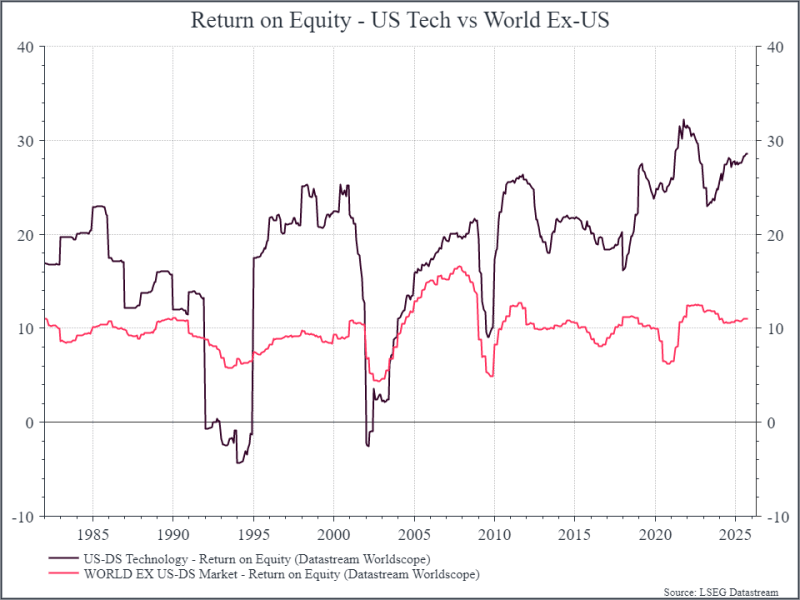

Looking at return on equity (ROE) – a broad measure of corporate returns – we can see that US tech has performed well. The chart below shows the ROE for the US technology sector and the world excluding the US. The gap between the two has widened steadily over the past fifteen years – a pattern that mirrors what we briefly saw during the internet boom, highlighting a similar buildup in expectations.

The rising ROE in US tech highlights again that investors haven’t just been buying future hopes and dreams: technology earnings have grown quickly and the returns that these businesses generate are high and rising. But one key question is whether that will still be the case in the wake of all the investment that we’re currently seeing.

The fundamentals look pretty robust, even if valuations are above their long-term averages. That might mean muted long-term returns, but it doesn’t necessarily shout “bubble”.

Why demand is the real test

Looking forward, the question is whether all the capital investment that large tech companies are making will earn a decent return. As mentioned before, the absolute numbers are very large.

The good news is that many of the businesses making those investments typically generate a lot of cash, and they’ll be able to fund some part of that investment themselves. And we expect that there’ll be partners available to help fund the remainder.

But just because you have the cash to invest, doesn’t mean it’ll be positive for the business. We think the real question is on the demand side. Weaker-than-expected demand will leave these businesses with assets (data centres) that aren’t generating much of a profit. We would see that reflected in disappointing earnings growth and a lower return on equity.

It would be consistent with what we’ve seen in the past: too much capital chasing too few opportunities. So far, we believe demand remains solid. Second-quarter earnings growth for US tech companies was strong, and recent signals from the technology supply chain – particularly from TSMC, the world’s largest contract manufacturer of semiconductors – indicate that demand has stayed strong into the third quarter as well.

We’ll get a better sense of that in the coming weeks. There are some warning signs, notably some complicated deals that are effectively vendor financing, where tech companies effectively provide the resources for customers to purchase their products.

Where does this get us? The current environment has similarities with past bubbles – notably, a potentially transformative technology, huge amounts of investment and high expectations. But it’s worth noting that underlying demand looks robust, profitability remains high and most of the listed businesses investing in the new technology are highly cash generative. Based on their current plans, they’ll need to be.

For now, we think that the case for an AI bubble hasn’t been proven, but expectations are undoubtedly high. We’ll need to keep a close eye on demand to see whether AI adoption continues to grow, and whether the major tech hyperscalers – large digital platforms capable of operating at massive scale – are able to translate that adoption into earnings growth.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.