Since the start of summer, one of the most pressing questions for investors and politicians alike has been whether or not the US is actually in a recession.

Part of the question is semantic, but it’s of great importance to investors. The US is, after all, where the greatest concentration of our equity investments is held. There are a few different definitions of a recession – the textbook one is that it begins after “two consecutive quarters in which the economy contracts.”

By this definition, the US would have entered a recession in the summer of 2022. According to a number of economists, however, this isn’t an appropriate measure, with them instead focusing on GDP growth data. A recession, then, would trigger in the event of a significant and lasting deterioration of the economy. In this instance, it’s difficult to argue that the US economy is contracting.

Despite widespread concerns, there are positive signs coming from the labour market, for example, which continues to see full employment and nominal wage growth. Nominal GDP is also growing, though the reality is that it’s slightly decreasing in the face of high inflation.

Over the last quarter, listed companies continued to record growing profits. World trade is also growing – even in Europe, despite the energy crisis, markets expect earnings to continue to grow. Household consumption has held up so far and some sentiment indicators (like the ISM manufacturing index) are showing positive signs.

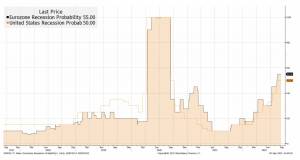

On the other hand, the issues caused by high inflation cannot be ignored, with many families and businesses likely to face difficulty over the winter. The prospect of a large rate hike by the Fed is also a concern, as we can see from economists’ estimates of the likelihood of a recession by 2023, which has grown considerably in both the US and Europe.

In short, the economic context is inconsistent. The takeaway is that the imbalances caused by the pandemic, and the subsequent government interventions that Covid necessitated, have led to an explosion in prices and a peculiar situation that’s difficult to properly define. Is this the calm before the storm? Or will the economy continue to be resilient, gradually returning to something resembling normal without too many dramatic corrections.

Hard data vs soft data

One way to try and answer this question is to analyse the discrepancies between the so-called ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ data. Or, data that measures the sentiment of economic operators (soft – generally these are surveys and are therefore more subjective), compared to consolidated statistics on the performance of the economy (hard, and completely objective).

As we’ve already said, the perception is that the soft data points to a situation that is far worse than what we see in the ‘hard’ macro data, which has been fairly positive. It’s possible to read this two ways: is the soft data that predicts a worsening economy valid or, on the contrary, is the current economic situation a victim of unjustified pessimism?

In the past, sentiment indicators have often come before actual macro data, deteriorating a couple of months before the crisis is reflected in the real economy. However, we’ve also seen the opposite effect. For example, in the pre-pandemic period, there was more optimism than the data warranted, perhaps a result of the combination of low inflation and low unemployment.

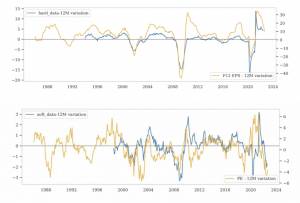

We also looked to link these variables to equity valuations. The first chart shows the relationship between the macro data and the changes in earnings, or the actual performance of the companies. The second chart shows the relationship between the soft data and the changes in the price/earnings ratio. We can see a clear relationship between earnings and the real economic data, while valuations tend to follow sentiment indicators.

This is best explained by the fact that, in the short term, valuations are more inclined to follow the sentiment rather than the fundamental data, even if it’s the data that dictates the actual performance of the companies, and in turn their share price.

Even taking into account the limitations of this analysis, the relationship between hard and soft data and equities suggests that, while we’ve seen a downgrade, we probably haven’t seen the end of earnings downgrades. This supports maintaining a cautious stance.

Is a soft landing possible?

It’s not all doom and gloom, though. Sifting through the data, you’ll find indicators that remind us that it’s still possible for the US to avoid a recession.

Central banks will play a crucial role if the soft landing is to be achieved. Interest rates have already begun to rise (and are likely to increase further), and it’s reasonable to argue that the economy is yet to be fully affected.

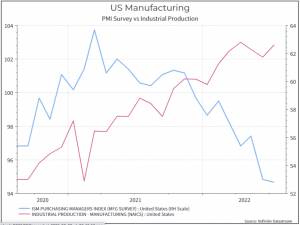

As we’ve already touched on, the macro data coming out of the US continues to be decent. The chart below shows the ISM surveys for the manufacturing and services sectors. The data is clearly weakening but it remains above 50 points, which suggests that the economy is still growing.

The next chart shows the manufacturing PMI and the manufacturing output (soft survey data against hard macro data). Industrial production data looks more resilient than survey respondents’ sentiment, at least for now.

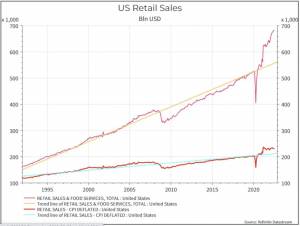

In terms of consumption, the graph below of retail sales (both nominal and real) suggests that the economy is still growing.

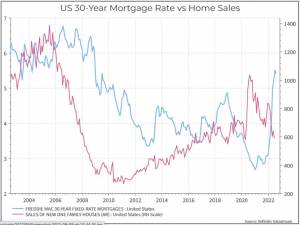

On the other hand, we can’t ignore the warning signs. The chart below shows house sales and mortgage rates. The rise in rates has had a negative impact on new house sales and this will almost certainly have an impact on the wider economy.

It might be reasonable to argue that the economy is simply beginning to react to more restrictive monetary policy. It usually takes a number of quarters before the impact of higher rates makes its way into the real economy. We are, however, already beginning to see the impact on inflation expectations.

In the graph below, the blue line shows the inflation expectations for this year, which have fallen sharply over the past couple of months. The other two lines take a longer-term view, with the expectations for the next couple of years dropping slightly, reflecting improvements on the supply side (lower transport costs, shorter delivery times) as well as a probable slowdown in demand.

Resilient macro data and improving inflation expectations are positive signs, suggesting that the US may be in a better position for a soft landing than other economies in the developed world. More so than in Europe/the UK, we see strong underlying data and slowing inflation, with the central bank well on its way to raising rates. All of these signals mean that it is too early to announce a recession (indeed, experts put the chances of a recession at about 50%).

So, we’ll see. For now, though, despite the tempting valuations, we remain confident in our conservative positioning.