“We will have an economic and financial catastrophe.” These are the words of US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen on the US debt situation, recalling how it’s the explicit task of Congress to ensure this doesn’t happen by raising the debt ceiling, to provide longer term certainty and ensure the US government is able to make payments. Yellen’s remarks were clearly designed to draw attention to the gravity of the situation and urge lawmakers to act responsibly in their decision making when deciding on any potential debt ceiling and its deadline.

The debt ceiling is essentially a public finance control tool created in 1917. Before then, every debt issuance had to be passed by Congress. However, to meet the costs associated with entering the first World War, the American government needed more flexibility, so the legislative process was modified to be able to utilise debt more easily but still remain within pre-established limits. Since then, the debt ceiling has been the main tool with which Congress can control any public spending that the government implements.

The situation in the US is currently critical given that, according to Yellen’s forecasts, should a solution not be found (i.e. if Congress does not decide to raise the debt ceiling), the US could risk default as early as the beginning of June – a deadline on which not all politicians in Congress agree. The problem is in fact political , as Republicans believe there is still time, assuming a July or August deadline instead, and therefore believe there is no need for a compromise at the moment. Negotiations, though, are still ongoing, and there is hope that an agreement can be reached between lawmakers on both sides of the aisle.

This stubbornness was not conceived by the Treasury, which started to talk to members of the Bank Policy Institute (a pressure group whose board is led by JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon and which includes Citigroup CEO Jane Fraser) to discuss the impasse on raising the government’s debt limit. However, it is worth remembering that this is far from the first time things have gone down to the wire – there are often last-minute agreements that have been reached, and this may be the case once again.

Why are we here?

Over the past 30 years, the debt ceiling has been raised numerous times, with greater frequency and intensity during crises such as those seen in 2008 and 2020.

What makes the current situation controversial and potentially dangerous is the considerable polarisation of the electorate and, consequently, the political structure of Congress. This is a situation that makes mediation and finding a meeting point to resolve the debt situation more difficult.

From a financial markets perspective, we are seeing an interesting divergence between what the money and bond markets are pricing in on this event and the moves in equities.

Investors have started to price in the possibility that the government may not be able to repay bonds due in June through various means.

Firstly, the odds of a Fed rate cut. Independent though the central bank is, it is hard to imagine that there would not be a shift in monetary policy towards easing in the event of a fiscal unrest. This has already been reflected in the rather aggressive path of cuts priced in by the markets recently.

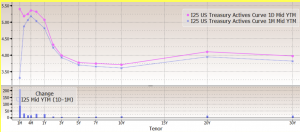

Secondly, the interest rate curve. The chart below clearly shows how in the last month, the rate of return required by investors for US government bonds maturing in one month is abnormally high compared to the rest of the curve. This increase occurred mainly over the last month.

Stock markets, on the other hand, are proceeding undaunted for now, without giving too much weight to the chances of a possible default. This is partly rational, as investing in stocks usually implies a multi-year time horizon, but on the other hand, it sounds an alarm about investors’ ability to consider this type of risk.

At the moment there is no consensus on any potential ‘expiration date’ for US solvency. The fact is that the speed with which the US government has depleted its reserves at the Fed – essentially the state current account – in recent months is concerning.

Since May 2022, the balance has fallen by $810bn, exhausting any excess liquidity created by covid. The level in itself is not abnormal compared to pre-pandemic levels, but if put into context alongside public spending and higher levels of debt, it is clear that the situation is more precarious than it has been in the past. In fact, it is estimated that, for this year alone, debt servicing costs will be around $900bn.

Some analysts see the first half of June as the key period. In fact, an important fiscal deadline falls in mid-June that could fill the state coffers, but it could already be too late. Conversely, other analysts have pushed the expiration date further into the summer.

What is certain is that the consequences of a potential default, even a purely technical one, are almost unimaginable. That being said, it is in the interest of all parties concerned to find a path forward, and it is likely that an agreement – albeit later than many would perhaps like – is on the horizon. The situation is constantly evolving and we will continue to monitor these developments closely.

As talks over raising the $31.4 trillion debt ceiling go down to the wire, markets and investors remain jittery. Discussions, which stalled on Friday after a Republican walkout, seem back on track for the moment as President Biden and Speaker McCarthy had a phone call on Sunday night, with good progress reported by both sides and a further meeting scheduled for Monday.

It has to be reiterated that the US is heading to an extraordinary territory, with global consequences. Failure to raise the debt limit will push the US to default on its bills, which would see Federal workers furloughed, global markets crash and plunge the US economy into a recession.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.