What are we talking about? The Chancellor announced details of a so-called “mini budget” on Friday. The policy signals were quite significant and the market reaction was abrupt.

What was notable? There are a number of pieces of news that caught our attention.

1. Tax cuts and Growth: The new government is focused on economic growth – with a target of 2.5% annual growth. They believe that tax cuts are an important tool to accelerate it. To that end, the Chancellor announced the removal of the 45% top income tax bracket, that he would cancel the planned increase in the corporate tax rate from 19% to 25% and planned increase in National Insurance, remove the cap on “bankers bonuses”, repeal IR35 (off-payroll reform) among other things.

2. Improving the supply side: The Chancellor announced plans to make it easier to start infrastructure investment and promised a list of projects that would begin.

3. Silence from the OBR: There was no comment from the independent Office of Budget Responsibility on the economic impact of these announcements, but the Chancellor did promise that the OBR would be able to review the plans before the end of the year. The absence of any OBR forecasts has been criticised by the chair Treasury Select Committee.

4. Independence: The Chancellor commented that the independence of the Bank of England was “sacrosanct”.

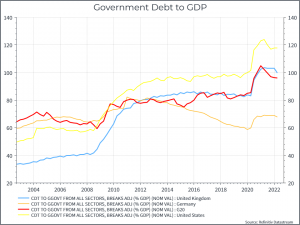

5. Debt to GDP: The Chancellor commented that UK government debt to GDP is low by G7 standards and that he expected debt to GDP to fall in the medium term

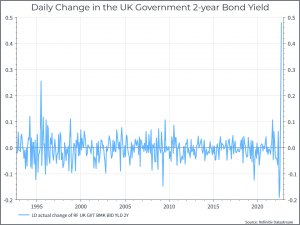

6. Market Reaction: UK financial assets sold off on the news of the budget. Sterling weakened over 3% against the dollar, UK government bond yields rose, with a core UK government bond ETF dropping 2.6%. To put the day in context, the chart below shows the daily change in the UK 2-year government bond yield over the past thirty years.

How should we think about all this? There are a few points worth making.

1. The government is making a pretty big bet that tax cuts will translate into growth. We don’t think the argument for this is particularly compelling – at least at these tax rates, even if it’s fair to say that the tax burden in the UK is high versus history.

2. The silence from the OBR is notable. These tax cuts are unfunded, in the sense that there was no cost-cutting announced on the other side. The implicit argument is that faster growth will produce higher tax revenues and pay for itself in the end. You’d guess that that is why the Chancellor believes UK debt to GDP will fall in the medium term. If you don’t subscribe to that view (and you’d guess that the OBR doesn’t), then debt to GDP would continue to rise.

3. On the topic of debt to GDP, the chart below shows debt / GDP data from the Bank for International Settlements. It shows the UK roughly in line with the G20, better than the US, and some way higher than Germany. The Chancellor’s point is fair as far as it goes, but he doesn’t mention a) that debt to GDP has risen globally post-pandemic and b) that the growth in UK debt to GDP over the past twenty years has outstripped the G20 by some margin.

4. This brings us to the market reaction – which was distinctly unimpressed by the proposal. A cynic might ask – why aren’t these bankers happier if they’re going to pay less tax? The answer is that they’re not bankers (at least for these purposes), they’re the people who’ll be asked to pay for this plan – by buying government bonds. And if you’re asking them to buy much more of them, then the price is going to come down.

5. And that brings us to Central Bank independence. During the leadership campaign, the Prime Minister floated the idea that maybe central bank independence wasn’t such a good idea. For now, at least, the government seems ready to leave that particular dog asleep. But if bond yields keep rising, maybe the government will think more closely about the value of an independent monetary policy and that, we think, financial markets will not take well.

6. The final point is around inflation. The plan calls for an expansionary fiscal policy in a period of high inflation. Traditional macro theory suggests monetary policy, i.e. interest rates should tighten to offset that.

Where does this get us? The government has made a bet on faster growth through, in the first instance, tax cuts. The people who are being asked to pay for it (broadly speaking, financial markets) don’t like the idea. We can see why – there’s a decent possibility that the outcome will just be higher debt for not much more growth. The less they like it, the more difficult the plan becomes.

We’d expect the government to stay the course for now – it’s only been a day, after all! UK assets look cheaper than they did, but the risks have risen too. As you’d guess, in this environment we think that having a globally-diversified portfolio makes even more sense.