Richard Flax, Chief Investment Officer

Prime Minister Boris Johnson failed to deliver on the promise that landed him the top job; the UK’s exit from the European Union on 31 October. Instead, we’re headed to the polls once again, but will his General Election gamble pay off?

Importantly, this is the fifth ‘moment’ of political uncertainty in just three years. Since the 2016 referendum, there have been two Prime Minister changes and this will be the second snap election. This era of uncertainty is taking its toll, with indicators of UK economic activity volatile in recent quarters.

So, the UK is going to have a general election on 12 December. It might matter. It might not. We might all prefer to stay home and hide under the covers in a vain attempt to make it all go away. But, we should probably think about what the outcomes could be and why they might matter for financial markets.

Ostensibly (as far as I can tell), we’re having an election because Boris Johnson actually got a Brexit deal passed by parliament. He then insisted that parliament spend no more than three days analysing it.

A majority of MPs decided that wasn’t a very good idea – since it was quite an important piece of legislation and they had spent longer picking a sofa. Boris then basically threw his toys out of the pram and, faced with another tantrum, MPs did what exasperated parents so often do – they gave in.

Why are we really having an election?

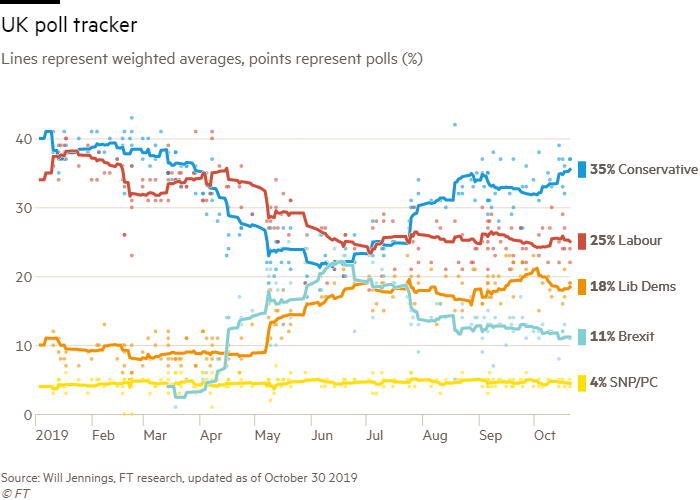

The chart below shows why we’re really having an election. First, the juicy 10% gap between the Tories and Labour is simply too appealing for a minority government.

If voting follows the polls (and that’s a mighty big “if”), then the Tories could end up with a fifty-seat majority. Enough to deliver their Brexit deal (or even perhaps no deal in two years’ time) and actually then govern the country (which would be novel).

Second, an election might allow the Liberal Democrats to re-emerge as a credible electoral force. They might not be able to stop Brexit, but they could establish themselves as a true centrist party in a world where Labour and the Tories have drifted increasingly to the extremes.

Third, the SNP see Brexit as a path to Scottish Independence. So the sooner we can get there, the better (for them).

And, finally, Labour have run out of excuses. No-deal is theoretically off the table and even if no one is quite sure what their Brexit policy actually is, they’ll work very hard to make this election about something else.

What about some probabilities:

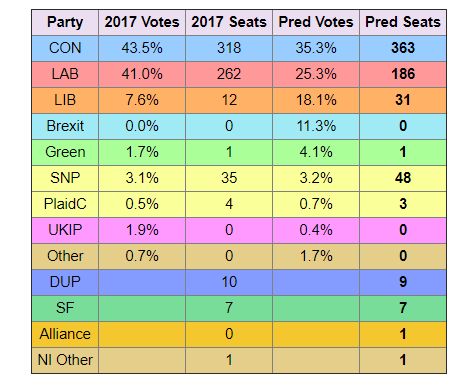

The data below is shamelessly lifted from the Electoral Calculus website. It tries to answer an important question – how could opinion polls actually translate into seats in parliament?

The table below reiterates the points made above. They’re predicting a Tory majority and gains for the Lib Dems and SNP, at the expense of Labour.

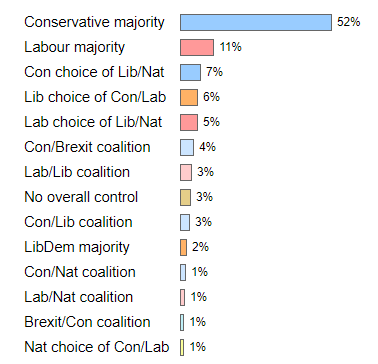

The table below tries to apply some probabilities – the headline is a >50% likelihood of a Tory majority, but there’s still a long tail of messy randomness that might occur.

What does it all mean for financial markets?

Crudely, we think it’s something like this:

- A Tory majority and a deal (of almost any sort) should be positive for UK risk assets.

- A Labour majority would probably be taken negatively – largely for reasons unrelated to Brexit.

- A hung parliament would probably be a short-term negative, given the uncertainty it would create, but it’s unclear where that would leave Brexit.

One more point worth reiterating. Even if we have a Brexit deal and a government with a working majority – a deal would likely be just the end of the beginning of the Brexit saga.

How we have positioned portfolios

The outcome of Brexit is no more certain. Some adjustments were made to Moneyfarm portfolios in September, and we’re still not keen to aggressively bet on any one political outcome.

Against a backdrop of Brexit, the US-China trade spat and slowing growth, we adjusted our fixed income exposure, without impacting the expected returns of the Moneyfarm portfolios.

As our positions in global fixed income helped limit the impact of volatility over the last few months, the Investment Team looked to shift some of the UK exposure to take advantage of global opportunities.

In portfolios with a low to balanced risk exposure, the Investment Team reduced our positions in UK inflation-linked bonds in favour of currency hedged global sovereign bonds.

In higher risk portfolios, we increased the yield by swapping UK sovereign bonds short-maturities for global sovereign bonds sterling hedged, and global investment grade credit denominated in US dollars.

Since, the additional US dollar exposure has been hedged to maintain what the Investment Team views as an appropriate level of sterling exposure, we were able to pick up some yield without adding currency risk.

Moneyfarm Portfolios are more globally diversified. By increasing exposure to the US, the Moneyfarm Portfolios are in a better position to take advantage of the Fed’s more cautious approach to monetary policy, which should support financial markets over the short-medium term.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.