By Richard Flax, Chief Investment Officer

The strength of the US economy in 2023 caught many investors by surprise. Faced an inflation shock, the Federal Reserve had hiked policy rates aggressively and the odds of a recession looked pretty good.

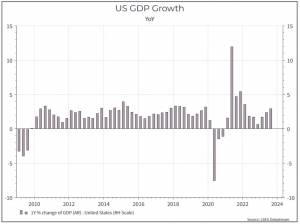

Instead, the labour market and the US consumer in particular held up pretty well, and the US economy continued to expand. The chart below shows year-on-year GDP growth. We did see a slowdown in the 4th quarter of 2022, but beyond that, the impact of higher policy rates is still to be seen.

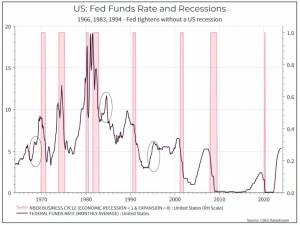

It’s unusual to see a significant tightening cycle that doesn’t prompt a recession, but it’s not unheard of. The chart below illustrates the point. It shows the Fed Funds rate and “official” US recessions. We can see that tighter monetary policy has often preceded recessions, as you might expect, but that on at least three occasions (1966, 1983 and 1994) higher rates didn’t prompt a recession.

So, how should we think about 2024? First, inflation has come down. The chart below shows headline and core inflation gradually moving towards the 2% target.

There’s still a way to go, but the improvement has been clearly visible. That should allow the Federal Reserve to reduce rates at some point in 2024, even if the precise timing is unclear.

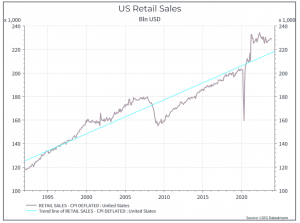

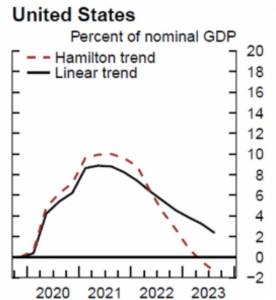

Second, we should acknowledge the resilience of consumer demand. The chart below shows retail sales adjusted for inflation. After the post-COVID recovery, retail sales have remained some way above their long-term trend. You might expect that to move back towards the long-term trend.

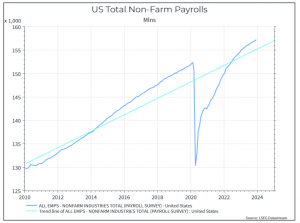

A robust labour market explains part of that consumer demand. As the chart below shows, non-farm payrolls have continued to grow after the economy re-opened.

But we have seen some signs that the labour market is slowing. The number of job openings has come down, as has the number of companies struggling to fill positions (see chart below).

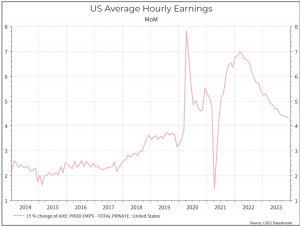

At the same, wage growth has begun to slow, even if it’s still at a pretty healthy level.

Another argument that is often put forward is about “excess savings” – that households saved a lot of the government support they received during COVID and have been spending that over the past few quarters. According to Federal Reserve estimates, those excess savings in the US are almost spent.

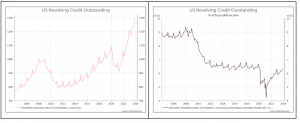

But the signals from consumer credit are still a bit mixed. If we look at the absolute level of consumer credit, it seems high. But if we see credit as a percentage of disposable income (right-hand chart), it seems much more manageable.

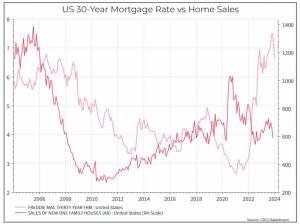

And higher rates have clearly had an impact on the housing market. The chart below shows how new home sales have dropped in the face of higher mortgage rates.

Overall, we think the US economy looks pretty robust and much stronger than many would have expected a year ago. We are seeing some signs of slowdown, and we’d expect that to continue. But the base case for now is that the economy is likely to avoid a recession in 2024 and that should be enough for the “soft landing” contingent to declare victory.

How could that view be wrong? There are a few scenarios to consider. The first is that the economy is actually weaker than we think – it just hasn’t shown up in the numbers. We know that monetary policy operates with a lag and we suspect that excess savings have supported consumption. Maybe that will come to an end. We think it’s a fair concern, even if we’ve heard it for some time.

The second scenario is around inflation. Either inflation proves stickier than expected one more time, and the Fed keeps rates higher for even longer. Or, inflation re-accelerates in the face of lower rates (say because the labour market picks up steam again) and the easing cycle of lower rates proves short-lived. That might not be enough to cause a recession in 2024, but it might raise some questions about 2025.

Finally, we should acknowledge the role of outside shocks. The Fed is not as omnipotent as you might imagine. There’s an argument that the Fed hasn’t really had much to do with lower inflation and that it’s really about things like improvements in the global supply chain. If that’s true, then another supply shock – conflict in the Middle East or Asia for instance – could hit inflation and consumer confidence again.

But when we put all those risks to one side, the outlook for the US economy in 2024 remains fairly benign and the Fed, which would have certainly taken the blame for a recession in 2023, can breathe just a little easier.

The views expressed here should not be taken as a recommendation, advice or forecast. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

With investing, your capital is at risk. The value of your investment can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invested. You should seek financial advice if you are unsure about investing. The views expressed here should not be taken as a recommendation, advice or forecast.

Richard Flax: Richard is the Chief Investment Officer at Moneyfarm. He joined the company in 2016. He is responsible for all aspects of portfolio management and portfolio construction. Prior to joining Moneyfarm, Richard worked in London as an equity analyst and portfolio manager at PIMCO and Goldman Sachs Asset Management, and as a fixed-income analyst at Fleming Asset Management. Richard began his career in finance in the mid-1990s in the global economics team at Morgan Stanley in New York. He has a BA from Cambridge University in History, an MA from Johns Hopkins University in International Relations and Economics, and an MBA from Columbia University Graduate School of Business. He is a CFA charterholder.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.