The global shortage of semiconductors has come as the result of a perfect storm in global economics and logistics. The scarcity of the components – and, by extension, consumer tech products – can be largely attributed to the pandemic, but there is more to the story than just lockdown.

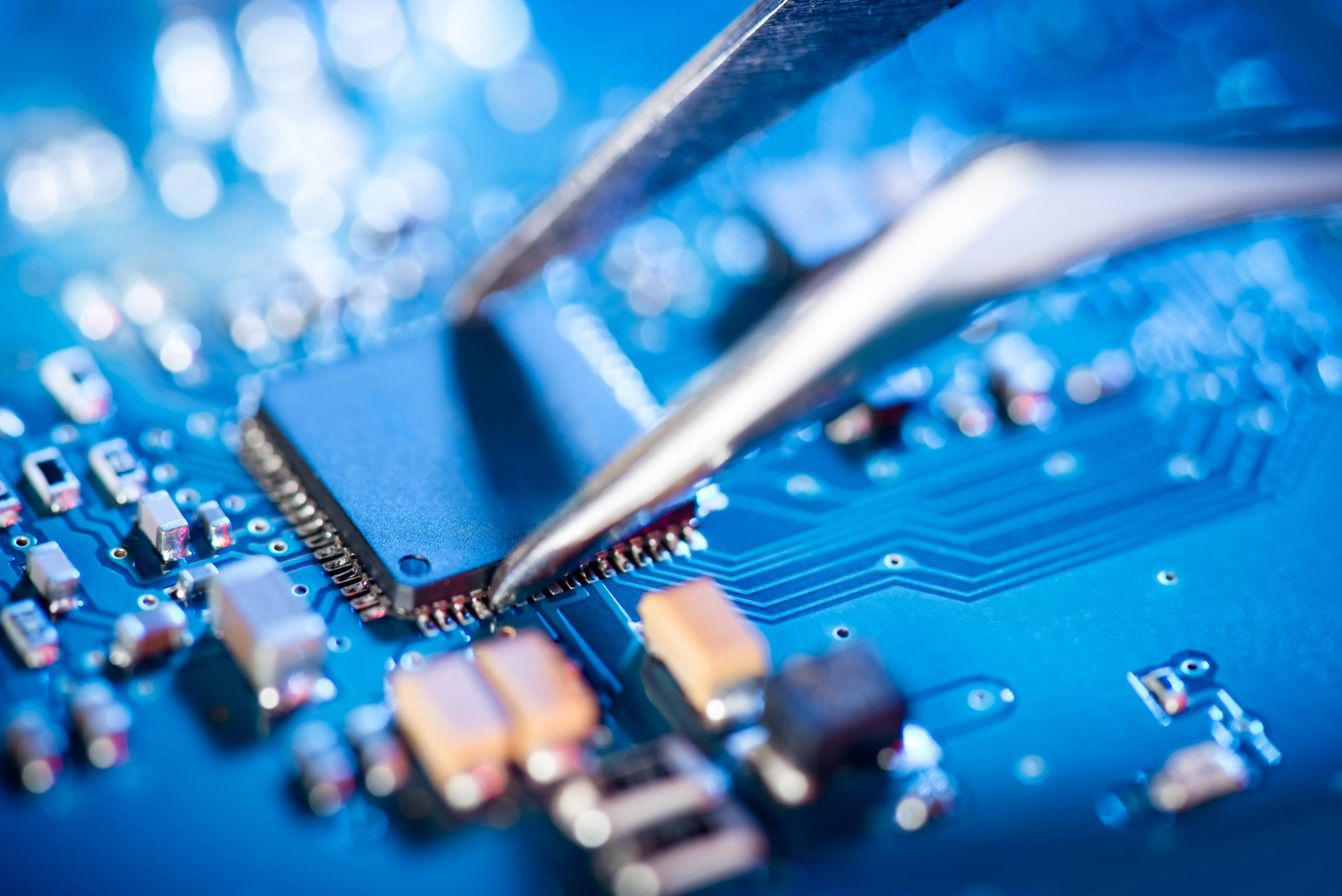

Before we go on, let’s quickly establish what semiconductors actually are. Semiconductors are a common feature in electronic circuits. As the name implies, they act as conductors in some instances but can also act as insulators, depending on the circumstances. In short, they appear in just about every popular piece of consumer tech there is and are, as a result, a pillar of the modern technology business.

The first lesson of economics is scarcity

So, how did semiconductors go from commonplace to scarce? A large part of the answer can be found in pandemic-related lockdowns. As governments have attempted to grapple with the spread of Covid-19, the most effective way to limit the spread has been to keep people at home.

This, unsurprisingly, has led to a surge in demand for consumer technology. Not only have people been looking for ways to pass the time, they also (in many cases) have significantly more disposable income than normal. Personal computer sales, for example, have surged amid lockdowns as people do their working, socialising and shopping from within the confines of the home.

Another major contribution to semiconductor demand has been the server sector. Server sales saw a year-on-year spike of 21%, with the explosion in online activity and remote working increasing the need for server capacity exponentially. What all this ultimately means is a sharp spike in demand for semiconductors globally.

According to Cisco boss Chuck Robbins, the scale of the demand for semiconductors has taken entire industries by surprise. “Everyone thought that the demand side was going to decline significantly and, in fact, we saw the opposite,” he told the BBC. “We saw the demand side increase.” The result of this mass miscalculation was lower demand signals being sent to manufacturers of semiconductors, who even reduced their capacity in some cases.

The effects of the semiconductor shortage haven’t been limited to technology companies. In reality, you’ll find them in industries ranging from storage to automotive. In terms of global sales by usage, traditional PCs and tablets (13.1%) are second only to mobile phones (27.2%), but other areas like industrial electronics (8.4%) and servers (9.6%) also make up sizable chunks.

A symbol of the US-China rivalry

If there’s one component that best encapsulates the economic power struggle between the US and China, it’s the semiconductor. After all, the first and second largest economies in the world are locked in a confrontation specifically centred around technological dominance.

To get a flavour of the competition, you only have to look at the sanctions placed on some Asian businesses by the US over the last couple of years. Since May 2019, for example, the US has laid restrictive sanctions on telecommunications giant Huawei, including a ban on all US and foreign semiconductor companies selling chips using US technology to Huawei. Similar bans have been threatened towards apps like TikTok and WeChat, Chinese giants that the US fears could grow to dominate.

Semiconductors, along with the sector that produces them, sit at the heart of the rivalry. Among semiconductor companies, the global sales exposure to China averages 27%, with some as high as 50% – these are businesses that, if the economic tensions were to escalate, could find themselves subject to sanctions and limitations on where and how they trade.

How the shortage has impacted the markets

In the short term, a shortage of semiconductors is likely to be taken negatively by the market. The shortage of semiconductors is symptomatic of broader supply chain challenges around the world, as the global economy tries to restart itself. Those bottlenecks can potentially manifest themselves as higher prices and longer delivery times. That’s particularly relevant at a time when financial markets are very focused on the risk of accelerating inflation.

Delivery times for some types of semiconductors are at historical highs and that is likely to prompt slower deliveries, and possibly missed sales, for a range of products, from electric cars to computer tablets. If the impact is broad enough, we could see that reflected in possibly weaker earnings growth for a range of consumer businesses.

In the medium term, we’d expect supply chains generally to normalise, but we’ll still probably need to see an increase in semiconductor capacity globally. That sort of investment is costly and takes time – which could mean less cash flow for those companies today, but better growth in the future. There’s also likely to be increased focus on where those plants are located – as governments act to ensure security of supply for what is an increasingly critical product. Ironically, in the long-term, that might even mean an excess of global capacity. But we’ll cross that bridge when we come to it!

The shortage will end, but demand won’t

Ultimately, the semiconductor shortage will end. The bottom line is that, thanks to pandemic-related lockdowns and changes to working life, recent months have seen a boom in demand. This boom in demand was, unfortunately, met by a reduction in supply. Both of these factors will be resolved as we move further into 2021.

This isn’t to say that semiconductor usage will decline. You only have to consider China’s commitment to smart cities to get a picture of how important the technology will continue to be going forward. Based on IDC data, China’s investment in smart cities will rise at a CAGR of 13.5% over 2020-2023. Globally, the smart cities market is expected to grow at a CAGR of 24.7% from 2020 to 2027, according to a new study by Grand View Research.

Similarly impressive growth is expected in the automotive industry. BCA Research expects the global automotive chip market to grow at a CAGR of 9% from now until 2024, as it did between 2014 and 2019. This is largely due to the digitisation of the industry – the average value of semiconductor content in a standard vehicle is $330, while hybrid electric vehicles can contain anywhere between $1,000 and $3,500 worth of semiconductors.