Pensions shouldn’t be complicated, but they are, sadly. There’s no one-size-fits-all approach, but the key is to think long-term and keep costs down. And think through how much is ‘enough’. In this piece, special contributor and financial journalist David Stevenson explores how investors can approach pension planning with clarity and confidence, even in an uncertain environment.

If there’s one single idea I want to focus your mind on as a reader when it comes to pensions, it’s this: don’t overthink the tax wrapper you need, rather focus on thinking through how much you need for your later years, keep costs low, and then use whatever structure(s) make sense to you on a very regular basis.

What follows from this statement should be obvious to any informed reader. Once you commit to a pension, continue to pay in what you can afford safely. And keep those costs low because a pension is just a long-term, tax-efficient savings vehicle, and it shouldn’t cost you too much: remember that there’s nothing guaranteed in the world of investment except that excessive costs will destroy your wealth.

With these general truths out of the way, let’s confront another awkward ‘challenge’. I’m not sure if we designed a system to encourage long-term saving, we’d start with the current pensions system. It’s complicated, multi-layered, and for too many investors, way too expensive. The rules are deliberately confusing, and it’s easy to make mistakes or just throw your hands up in the air and say “heck, I’ll use an ISA!”.

In my ideal world, I’d redesign the ISA to make it slightly more user-friendly, eliminate all the variants, increase the amount you can pay in, and then overhaul the entire pensions system and start again. But as I am about as likely to get near the hands of power as President Macron is to find another prime minister to last through to the end of his term, that’s not going to happen.

We have to start with what we have, which is complicated: there’s no one-size-fits-all pension structure or product. You need to think through all the working parts of the pensions ‘maze’ and understand how much you need.

The foundational building block – at least for now, until a future government takes out a metaphorical axe and bashes in the triple lock on state pensions – is the state pension. For those reaching State Pension age after April 2016, the full new State Pension is £230.25 per week (£11,973 annually) for 2025/26. To qualify for the full amount, you need 35 qualifying years of National Insurance contributions, though you can receive a partial pension with as few as 10 qualifying years. The State Pension increases annually through the “triple lock” guarantee, rising by the highest of earnings growth, price inflation, or 2.5%. However, I wouldn’t rely on that triple lock for the long term. Think tanks on the right and the left are busy crunching the numbers on eliminating that triple look.

The next building block for most people is workplace pensions. Remember that auto-enrolment is mandatory for all UK employers: if you’re aged 22 to State Pension age and earn over £10,000 annually, your employer must automatically enrol you into a workplace pension scheme. The current minimum contribution rates are a minimum contribution of 8% of qualifying earnings, with the employer contribution set at at least 3% and the typical employee contribution (unless you opt out) at 5%. Again, I would wager a small fortune that those percentages will increase over the long term.

For the UK auto-enrolment scheme, contributions are calculated on qualifying earnings between £5,772 and £41,865 annually. You receive automatic tax relief on your contributions, and you can opt out if desired; however, employers are required to re-enrol you every three years.

Many old-fashioned workplace pension schemes were once called Defined Benefit (DB) schemes, where employees contributed and then received a fixed benefit, typically based on their final salary. Most private sector DB schemes are now closed to new members, although the vast majority of public sector employees still belong to DB schemes.

The last layer, which I consider the icing on the cake, is personal pensions, particularly self-invested personal pension plans (SIPPs). These are known as defined contribution (DC) schemes, which invest your money in various assets, with your eventual pension payout dependent on the contributions made and the subsequent investment performance.

As you can see, it’s all a bit of a regulatory maze, with numerous rules governing each structure and endless confusing acronyms floating around. Regardless of which pension you have – you could have multiple ones – there are some overarching rules. For the current 2025/26 tax year, you can contribute up to £60,000 annually (or 100% of earnings if lower) and receive tax relief. The tax relief works as follows:

- Basic rate taxpayers (20%): Get automatic 20% tax relief.

- Higher rate taxpayers (40%): Can claim additional 20% relief. Higher-rate taxpayers gain the most from pension contributions due to enhanced tax relief.

- Additional rate taxpayers (45%): Can claim additional 25% relief. However, be mindful of the tapered annual allowance if your income exceeds £260,000.

Non-earners can still contribute up to £3,600 annually and receive basic rate tax relief, effectively paying in £2,880 to achieve a £3,600 contribution. Crucially, if you exceed the annual allowance for contributions, you may use unused allowances from the previous three years through “carry forward” rules.

You can typically access private pensions from age 55 (rising to 57 from April 2028), and currently, though I would wager it will change, you can draw down 25% as cash straight away tax-free. With the remaining 75% of your pension at retirement age, you have several choices: you can, for instance, buy an annuity, which will provide a guaranteed income for life. The other main alternative is what’s called income drawdown, which keeps your money invested while you take regular or ad-hoc withdrawals. This offers flexibility but carries investment risk and requires active supervision.

Managing your own pension pot

An increasingly popular choice for self-driven, motivated investors is the Self-Invested Personal Pension (SIPP), which offers the highest level of control by allowing you to select specific investments, including shares, bonds, funds, and commercial property. SIPPs cannot invest in taxable property, which includes any property used or suitable for use as a dwelling, as well as tangible moveable assets such as art, antiques, collectables, fine wines, and precious metals.

Crucially, you can hold an unlimited number of SIPPs, but all contributions count towards your total annual allowance. And here’s another critical point to remember – you can transfer existing pensions into SIPPs without triggering contribution limits, although transfers from defined benefit schemes require specialist advice, as I mentioned earlier!

Let’s quickly swing through some common questions that get asked about pensions, especially SIPPs.

- Can you invest in both ISAs and pensions (including SIPPs)? Absolutely, and it often makes sense to do so. I recommend investing as much as possible in both. Remember, you can only invest up to £20,000 in an ISA, but you could invest as much as £60,000 per annum in a pension.

- Are pensions better than ISAs or vice versa? There is no definitive answer to this question. Both have their pros and cons. With pensions, you get tax relief on the way in (adds to your capital), but you pay tax on the income you take out of a pension. With ISAs, there is no tax subsidy on contributions as they are made, but once the funds are inside the ISA, there are no taxes (income tax or Capital gains tax) on the profits or income. ISAs are also quite flexible in that you don’t have to wait until retirement to access the investments. Everyone is different, but as a rule, assuming you are already enrolled on a workplace pension and young (under say 35), I’d probably be tempted to max out the ISA first, as it will offer you more flexibility, especially if you are saving to buy a property. Once you’ve passed that point, your priorities might change, and maxing out your pension might make more sense. However, if you are even the slightest bit unsure, seek qualified financial advice.

- Can I have multiple pensions? Again, the short answer is yes. Nearly everyone has the state pension, then there’s (hopefully) your workplace pension, and lastly, there are personal pensions like SIPPs, where you contribute individually and have more control. That said, in my humble opinion unless you have the time to keep track of numerous, varying pensions, it might make more sense to consolidate all your (private) pensions in one account and keep it simple.

- Do I have to do all the complicated asset allocation in a personal pension or SIPP or can I get someone to do it for me? Just because there are the words self-directed in the SIPP title, doesn’t mean that you have to do all the hard work of picking funds. You can opt for a managed plan, where a portfolio manager makes key decisions, and you simply provide them with your target retirement date or share some information about your risk tolerance. And what’s even better is that you can have a core managed fund solution and then run your own satellite portfolio where you get to make the key decisions.

What to watch out for

Now that we’ve worked through the complicated nature of pensions, let’s address some key issues investors need to be aware of. The first issue is one I have alluded to already – costs. Compound growth in capital is a wonderful thing over time – all those annualised gains slowly building on top of each other – but its nemesis (compound cost inflation) is also a threat. In my experience, many investors are somewhat naïve when they accept fees that add, say, 0.25% or 25 basis points (or more) to their total cost burden.

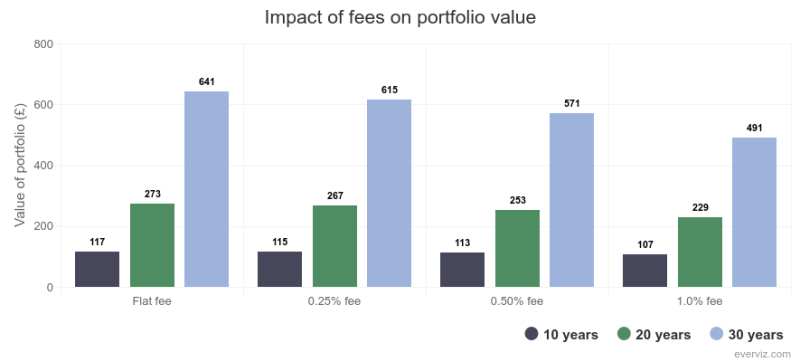

According to research by the reputable firm Kepler, pension (SIPP) fees can make a striking difference over time. As shown in the chart below, they found that the gap between a flat fee and a 1% platform fee could amount to around £150,000 over 30 years. Even a seemingly small difference — between a 0.25% and 0.45% platform fee — can add up to £45,000. And this gap could widen further if you achieve a 10%-plus annual return on your investments.

Fees can make a serious dent in the value of your pension

Source: Kepler calculations

Basis of calculations: initial investment of £50,000 with an annual growth rate of 9%. Flat platform fee of £100 in year one, growing by 5% thereafter

Remember that a pension boasts costs in numerous dimensions. There are the costs of the funds you invest, and then there are the costs of the platform that provides the pension. If all that weren’t bad enough, there may also be additional costs, such as drawing down a pension in retirement or setting up an annuity. All these costs add up and destroy your wealth. My rough and ready reckoner is that the total cost of all things related to your pension savings should never exceed 1.5% per annum and preferably be below 1%.

The next issue to watch out for is market volatility and risk tolerance. We’re all unique in our approach to risk and there’s no general rule that applies to everyone. Take the risk of market volatility, for example. One long-established principle is that young people – in their twenties, for example – can take more risks because they have a long time to ride out market volatility; thus, 100% exposure to equities makes sense.

However, studies have shown that many twenty-somethings are unfamiliar with the markets, and when they encounter a market sell-off for the first time, they become frightened. This impacts their long-term investing behaviour, and they become more skittish. As a result some pension plans allocate some cash to bonds for younger investors even though that defies some investment logic.

By contrast, another general principle is that once an investor reaches their early to mid-sixties, they should dial down risk, adopt a safe and defensive approach, and consider de-accumulation (drawing down capital). The snag is that many investors now live well into their late eighties and some into their nineties, and thus a strategy of taking risk off the table might not make much sense if they have to finance 30 or more years of retirement.

My point here is that risk is personal, and professional advice is crucial. Think of investment as a long series of windows, where you need to consider contrasting decades of market volatility and steady contributions. That requires you to have a good idea of when you want to take risk off the table, and also your willingness to take market volatility in your stride.

How much is enough?

I’ll conclude with what I think is the most challenging question: how much is enough in a pension?

Precisely because there’s so much complexity surrounding pensions, I think it’s essential to sometimes reduce the core challenge to a simple question: do I need £500,000, £750,000, or over a million to have a decent retirement? Once we have established that big number, we can then work backwards to build a long-term savings plan.

Let’s use some basic numbers to help answer that question.

- Assume the retirement age will be 67.

- Assume current prices and inflation

- Assume you’ve paid off your mortgage

- The current state pension is £11,973 for the state pension

- The Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association’s (PLSA) Retirement Living Standards survey provides a handy estimate, which was refreshed in June 2025 to reflect evolving retirement expectations, updated inflation assumptions, and the new full State Pension. A single person looking to have a moderate lifestyle would have a £31,700 annual spending target, or £43,900 for a comfortable lifestyle

- These numbers for a couple would be £43,900 for a moderate lifestyle and £60,600 for a comfortable lifestyle

- Remember that income from your pension is taxed at the usual income tax rates

Let’s first consider the comfortable single-person scenario. If they used what’s called an escalating annuity (which increases each year to help offset inflation), they would need £682,000 in their pot to generate the necessary after-tax income (including the state pension). For a moderate lifestyle, that amount reduces to £415,000. These annuity returns are actually quite generous – compared to the past – due to high annuity rates, and they could change significantly in the coming years. However, we have an initial estimate ranging from around £400,000 to nearly £700,000. For couples, the equivalent figures are £772,000 for a comfortable lifestyle and £418,000 for a moderate one.

These numbers above assume you buy an annuity, but that’s not the only option available. You could, for example, choose not to buy an annuity (remember that once an annuity ends, the capital is gone) and opt for an income drawdown in retirement. This allows you to remain invested in both bonds and equities while generating an income.

The key question then becomes how much I can withdraw each year. This is a complex subject, but there has been considerable research on the so-called SafeMax approach, also known as safe withdrawal rates, for US and UK retirees. Much of the best research has been conducted in the US, where a rate of 4% every year via a withdrawal was identified in the 1990s by a researcher. This figure enables an investor to remain invested in a combination of bonds and equities, while also accounting for potential market fluctuations. That is, there is no single year in which your investment plan is completely undermined, and you can maintain a 4% withdrawal rate over many years.

Subsequent work has suggested that this could be as high as 4.7% in the US, but more sobering studies in the UK have put our local SafeMax number down in the 3-3.5% range – a level I’d feel more comfortable with. If we assume, say 3.5%, then a £1 million savings pot could, on paper, allow a withdrawal of £35,000 per annum, which, when added to your state pension, brings your income before tax to around £47,000 – after tax, that would probably be a bit below the comfortable lifestyle number mentioned above, but you wouldn’t be far off. Crucially, your £1 million pot would be intact on your death (unlike with an annuity), although it would then be subject to inheritance tax.

Take control of your future with Moneyfarm

Finally, don’t let the complexity stop you from achieving your financial goals. Moneyfarm’s Self-Invested Personal Pension (SIPP) offers award-winning, actively managed portfolios built by experts to align with your risk profile and long-term goals. They simplify the complex world of pensions, help you consolidate old pots, and automatically claim your valuable tax relief, all while maintaining competitive, tiered fees. Take control of your future and discover your retirement wealth’s potential: explore the Moneyfarm SIPP and get started with a professionally managed, tax-efficient plan.

Please remember that when investing, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio with Moneyfarm can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The views expressed here should not be taken as a recommendation, advice or forecast. If you are unsure investing is the right choice for you, please seek financial advice.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.