Throughout May, both the Bank of England and the UK government were forced to respond to the cost of living crisis that’s been brewing in the country for months. The year to April saw inflation hit 7.8% and there are fears that we could see figures as high as 10% before the situation starts to improve.

These numbers are, clearly, far higher than the Bank of England’s target rate of 2%. Driven largely by soaring fuel costs – along with other necessities like food and housing – the average UK household is preparing to be notably worse off this year when compared to last.

When did the cost of living rise?

April was the month in which the majority of people began to worry about the cost of living. Firstly, and perhaps most impactfully, Ofgem raised the energy price cap by 54%, translating to a nearly £700 increase in yearly bill payments for those who pay by direct debit.

This, coupled with increases to national insurance, council tax and other bills like water and electricity has forced families to cut back on expenses. The situation is likely to worsen later this year, too, with another significant rise in the cap on utility prices planned for October.

With rent increasing for many, increases to benefits failing to keep pace with inflation, a rise in VAT for hospitality businesses and other contributing factors, the UK is on the verge of a serious cost of living crisis.

The Bank of England raises interest rates

So, how has the Bank of England responded? The Monetary Policy Committee (the MPC) of the Bank of England hiked its base rate by 25 bps to 1% in early May – a move that was largely in line with expectations.

The commentary from the Bank highlighted the challenges facing central bankers. The MPC highlighted the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – contributing to an increase in inflationary pressures and a weakening outlook for global, and UK, growth.

The table below from the May Monetary Policy Report illustrates the challenge for the UK economy more broadly, and the MPC more specifically. The figures in parentheses represent the Bank’s forecasts from the February report.

Starting with annual GDP (the first line), we can see a sharp downgrade in growth expectations for the year to 2Q 2023 (from 1.2% to zero) and for the year to 2Q 2024 (from 1% to 0.2%). On the inflation side, we see a steady upgrade in forecasts – representing a challenge for UK households. The Bank expects to see inflation back at its 2% target within the next couple of years, and then some way below target by 2Q 2025.

All things considered, the table is not particularly promising. Slow growth, high inflation, excess slack in the economy, rising unemployment and a higher policy rate is a challenging combination for the UK economy. The forecasts suggest that the MPC is keen to normalise inflation relatively quickly (at least officially), even at the cost of slower economic growth, and the 3 MPC members who voted for a 50 bp rate increase would support that view.

Rishi Sunak announces energy support fund

The response from the government came later in May, with Rishi Sunak announcing a package of measures to support households hit hardest by the sharp rise in the cost of living. The package is funded, at least in part, by a “windfall” tax on profits in the energy sector.

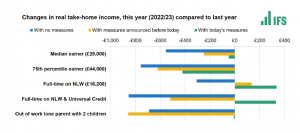

The headline numbers are, according to the Treasury, around £15 billion of additional support, targeted at lower-income households. The reaction has been fairly positive – according to the independent Institute for Fiscal Studies, it means that the median income earner will see their take-home pay stay roughly flat in real terms compared to last year. Lower-income workers will see a higher real take-home income, relative to last year. Higher earners will see some benefit, but far less, as the chart below illustrates.

The message from the government seems to be that these are one-off measures, but there could be more – presumably depending on how the economy develops.

The collective instinct of Conservative Chancellors has been to try to balance the books early, but the pressure on households has become too great, particularly given the prospect of another significant increase in the utility cap in October.

The government has increased its support for households in the wake of the very significant increase in the cost of living. It seems like the right thing to do, given the challenges facing households, particularly from rising food and utility bills.

On the margin, it’s probably supportive for growth – the outlook for UK growth looks pretty weak at the moment, as we’ve discussed – and for sterling, which has weakened against the dollar in recent weeks. But this isn’t a return to the generosity of 2020 and Rishi Sunak will be hoping, like the rest of us, that inflation will begin to slow without too much damage done to the economic outlook. It remains a difficult environment.

Whether the measures will prove to be enough to keep the UK economy ticking along and families afloat remains to be seen – it should be noted that the issue of high inflation is not limited to the UK, though it is being hit particularly hard. It also remains to be seen whether the “windfall tax” on energy companies will prove to be the correct method for easing the burden on families. As ever, we will continue to monitor markets and provide updates, and we will remain poised to make any changes to portfolios necessary to adapt to a shifting landscape.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.