Anyone walking through the streets of London on the morning of 19 June 1815 would have found the city hushed and tense, as if holding its breath. No one yet knew who had prevailed at Waterloo – Napoleon or Wellington. Rumours coursed through the lanes of the City’s financial quarter, deepening the sense of uncertainty. A French victory would have spelled disaster: wars, as history shows, come at a cost, and that cost is almost always borne by the defeated.

In the early hours, British government bonds came under sharp pressure. Amid the turmoil, a discreet German banker began to buy. Nathan Mayer Rothschild – according to a story that lies somewhere between history and legend – had learned of the British victory ahead of the market, aided by a network of couriers connecting the various branches of his expanding financial enterprise. While others were selling, he continued to accumulate. When the official news eventually reached London, prices rebounded sharply and Rothschild saw his position appreciate within hours.

Since then, the phrase attributed to him has taken on a life of its own: “Buy when there’s blood in the streets.” It encapsulates a view of markets rooted in opportunism, in which crisis is seen as an entry point. For much of the past two centuries, finance has often been described in these terms – a competitive arena where speculation, an integral part of market functioning, has frequently carried negative moral connotations. Although we should note that historical anecdotes are not analogous to investment processes and do not indicate any ability to forecast markets.

It was this moral instinct that laid the foundations for a different way of investing. The origins of what we now refer to as ESG investing – Environmental, Social and Governance – lie in the effort to place boundaries around a purely profit-driven logic. Over time, the realisation that profit at any cost is unsustainable has encouraged investors to explore alternative approaches.

As the concept evolved, ethical investing moved beyond a binary question of right and wrong. It began to be understood as a potential source of financial insight. In a world marked by intensifying climate, social and geopolitical pressures, investments can support the development of more resilient economic systems. Assessing not only returns but also environmental risks, social impacts and governance quality can provide a long-term advantage, offering investors a broader and more forward-looking perspective on risk and opportunity.

In this article, we will examine how ethical and alternative investing have evolved over the past fifty years – from the early emphasis on moral exclusions to the systematic integration of ESG factors into financial analysis and portfolio construction. We will also consider the questions and criticisms that have emerged along the way, and outline why we view ESG as increasingly central to the way long-term investing is understood and practised.

Religious morality as the starting point

The origins of what was once called ethical investing – and what we now describe as ESG – can be traced back to 1971. During the Vietnam War, two American Methodist ministers, concerned that their church’s savings might be supporting the production of napalm, launched what is considered the first “ethical” mutual fund: the Pax World Fund. Their initiative helped spark a shift in thinking that would evolve over the following decades.

At the time, “sustainable investing” largely meant aligning portfolios with personal or institutional values, mainly through exclusions. Investors would avoid the so-called “sin stocks” – sectors such as weapons, alcohol, tobacco and gambling – for ethical or religious reasons. It was a simple approach, but it provided the early framework on which later developments would build.

From ethical exclusions to the first sustainable funds

For many years, ethical investing was essentially defined by exclusions. Investors avoided sectors such as tobacco, weapons, gambling or highly polluting industries, creating a blacklist that reflected moral or social concerns. In the 1980s, this approach also showed its potential to influence real-world outcomes: the divestment campaigns against apartheid South Africa, led by pension funds and universities, demonstrated how coordinated capital flows could help exert economic pressure on a regime.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, responsible investing began to take on a more formal structure. The first indices and mutual funds built around ethical criteria appeared, and public awareness grew as events like the Chernobyl disaster brought environmental issues to the forefront. Even so, the sustainable fund universe remained small – a few dozen products with broad objectives and limited transparency.

During this period, new approaches began to complement simple exclusion policies. One of the most significant was the best-in-class method, which rewarded companies with stronger environmental or social practices within each sector, rather than ruling out entire industries. It signalled an important shift: from a purely ethical framework to a more strategic one, in which environmental and social factors were increasingly viewed as indicators of management quality and long-term financial risk.

Financial integration: ESG enters the mainstream

A turning point came in the mid-2000s, when sustainability formally entered the mainstream of financial thinking. Driven by a UN initiative, the 2004 Who Cares Wins report introduced the ESG framework and encouraged investors to consider environmental, social and governance factors as part of standard financial analysis. ESG was presented not as a purely ethical choice, but as a set of indicators that could help assess a company’s value and long-term risk.

This direction was strengthened in 2006 with the launch of the UN-supported Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), which set out practical guidelines for integrating ESG into investment processes. The initiative has grown from 63 original signatories to several thousand today. ESG-related risks are now widely recognised as material factors that can affect a company’s financial performance.

A growing body of research suggests that companies with stronger ESG practices tend to display greater resilience over time, while those facing serious environmental or social controversies often encounter financial repercussions – from fines and litigation to reputational damage and loss of market share. The link between sustainability and returns is not automatic, but the idea that ESG integration can support long-term risk management continues to gain ground.

Beyond profit: measuring real-world impact

Over the past three decades, another strand of ethical investing has developed alongside exclusion-based approaches: impact investing. Its aim is to generate measurable environmental or social benefits alongside financial returns. The focus is not only on avoiding harm, but on directing capital towards activities that can produce positive outcomes that might not otherwise take place.

This shift made the ability to measure impact increasingly important. During the 2000s and 2010s, a range of reporting standards and frameworks emerged – from the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) to the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) – providing more consistent ways to assess non-financial performance.

At the same time, asset managers began to develop tools to evaluate the environmental and social footprint of portfolios, from carbon emissions to labour practices across global supply chains. This helped clarify the difference between funds that simply integrate ESG considerations into their investment process and those that pursue a specific environmental or social objective, such as climate-focused strategies or social bonds.

In parallel, thematic sustainability funds grew rapidly, often centred on long-term structural trends linked to the energy transition, resource efficiency or demographic change. Their rise reflected growing investor interest in aligning capital with broader economic transformations.

ESG under fire? Doubts, criticisms, and responses

The rise of ESG has not been without its critics. Some view it as a form of greenwashing with limited real-world impact, while others argue that incorporating ESG factors inevitably comes at the expense of returns. The strong performance of oil and defence stocks from 2022 onwards has, in some cases, reinforced these narratives. Political cycles can certainly influence short-term relative performance, but climate risk, social tensions and governance failures remain structural forces that can materially affect long-term outcomes if left unaddressed.

Recent evidence, however, points to an ESG landscape that is evolving rather than retreating. Paradoxically, the energy shock of 2022 accelerated investment in the green transition. The International Energy Agency expects the next five years to deliver as much new renewable capacity as the previous two decades combined – a sign that the underlying drivers of the transition, and of ESG more broadly, remain firmly in place.

Towards the new grammar of investing

The evolution of ESG shows that ethics and financial returns do not necessarily stand in conflict. At Moneyfarm, we believe that, over the long term, the distinction between “ESG investing” and investing more broadly will gradually fade. ESG considerations are likely to become a standard component of assessing any opportunity, alongside traditional economic fundamentals.

This shift will be supported by the growing availability of high-quality sustainability data, advances in technology, the intensification of environmental challenges and broader cultural change – particularly the heightened awareness among younger generations. These forces are already shaping capital flows and will continue to influence market performance. Investors who understand this evolving framework will be better placed to identify emerging risks and opportunities.

What began in 1971 as the initiative of two idealists has grown into a global movement mobilising trillions and engaging investors of all sizes. Sustainable finance, while still evolving, is moving from its early stages towards maturity – aiming to generate long-term prosperity while remaining aligned with the needs of society and the environment.

A look at our portfolio performance

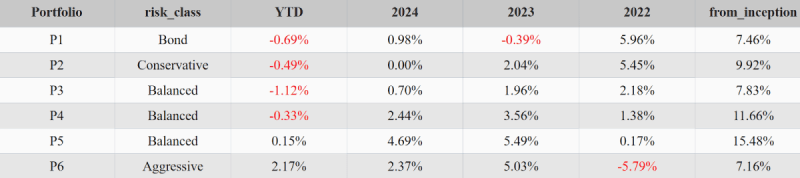

The performance of our portfolios is constantly analysed in both absolute and relative terms, benchmarked against traditional markets and similar ESG funds.

Over the three-year period from 1 October 2022 to 1 October 2025, our ESG portfolios have delivered solid absolute returns, with annual gains ranging from 4.22% in the lowest-risk portfolio to 10.80% in the highest-risk one.

| Portfolio | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 |

| Annual Performance | 4.22% | 5.46% | 6.01% | 7.36% | 8.99% | 10.80% |

From a relative perspective, we compare our performance with ESG funds aligned with our investment policy. Since the definition of ESG is currently very broad, it is not always easy to assess how a fund’s sustainability profile – such as its exposure to fossil fuels or ESG rating – affects its results. For this reason, we set clear criteria to ensure funds are genuinely comparable to our own, allowing us to smooth out differences and focus purely on performance.

To identify a strict subset of ESG peers, we consider only multi-asset funds with a clearly stated ESG policy, excluding those exposed to social controversies such as violations of the United Nations Global Compact. We also include only funds that meet specific improvement thresholds in terms of MSCI ESG ratings, fossil fuel revenues, and carbon intensity.

The table below shows the performance of Moneyfarm’s ESG portfolios compared with the median of this group of strict ESG peers, as of 1 October 2025 (net of management fees of the underlying instruments and gross of Moneyfarm commissions). The 100% equity portfolio is not shown because it does not have the same historical data as the other portfolios.

Relative performance since inception (31 October 2021) has been overall positive. The portfolios – particularly those with higher risk levels – have more than recovered the ground lost in 2022, when our stringent fossil-fuel exclusion strategy was penalised by market conditions.

Past performance is not an indicator of future results. Performance figures are net of ETFs Ter and gross of any Moneyfarm fee or taxes.

Long-term investing has always been about patience, balance, and confidence in one’s strategy. Embracing ESG builds on the same foundation: it’s an acknowledgment that responsible practices and sound governance are key drivers of enduring value.

Please remember that when investing, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio with Moneyfarm can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The views expressed here should not be taken as a recommendation, advice or forecast. If you are unsure investing is the right choice for you, please seek financial advice.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.