Volatility picked up in October, sparked by increasing geopolitical risk and economic uncertainty. Whilst equity markets felt the pressure, the US earnings season unveiled a solid backdrop, so does this mean US equity is now cheap?

Value, much like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. But for simplicity’s sake we’ll use the traditional Price/Earnings multiple to measure value. The ratio compares the price of an asset by the earnings it’s expected to generate in the future.

The higher the PE, the higher it’s valued – probably because investors expect strong earnings growth in the future. The lower the PE, the cheaper it is. Whether that means it’s good value is a different question, and one we’re going to look at here.

It’s never good to judge something by looking at a snapshot of performance in isolation – just like we don’t base our investment decisions on the PE alone.

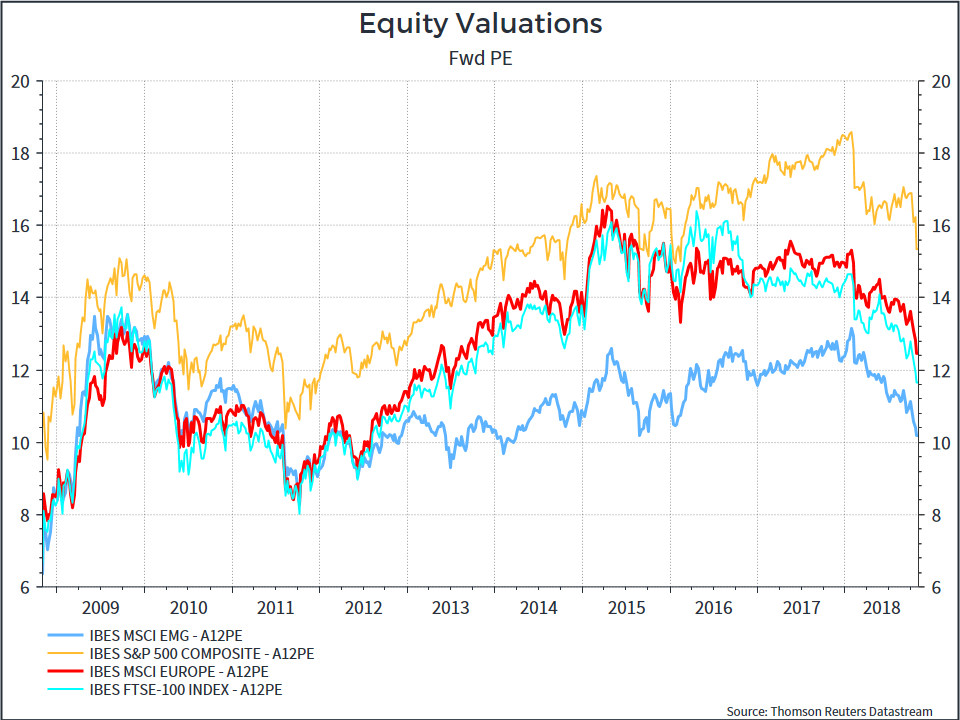

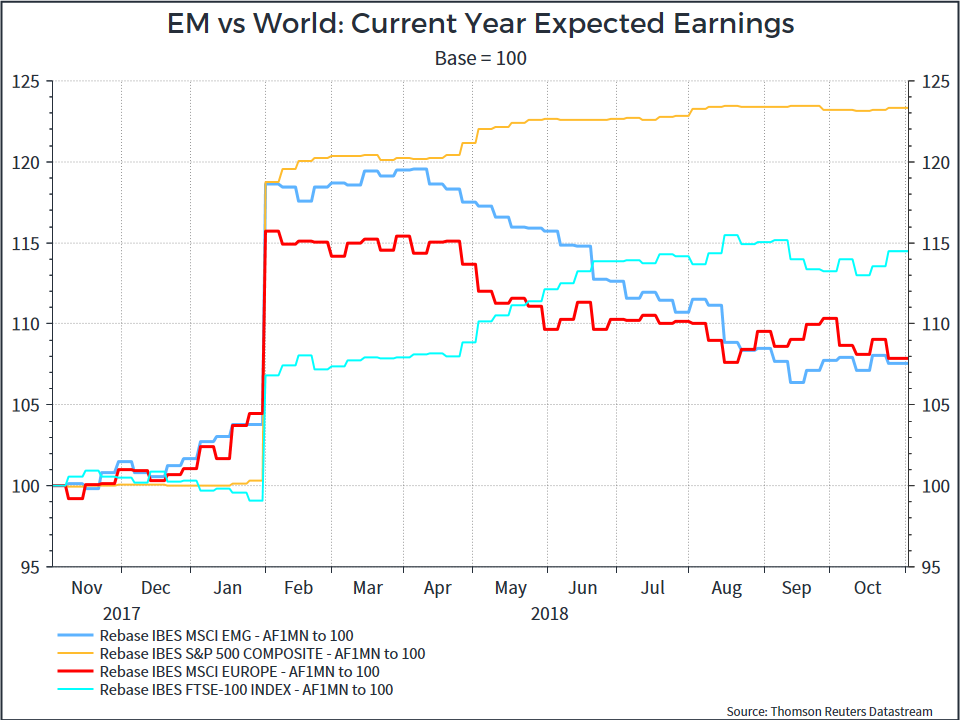

Here, we’ve compared the PE ratings of a range of equity markets over the last decade: Emerging Markets (blue line), US (yellow line), Europe (red line) and the UK (turquoise line).

Broadly, you can see a steady rerating as the PE ratios for each market rises up to mid-late 2017. The UK, however, sticks out with the PE under immediate pressure following the Brexit vote.

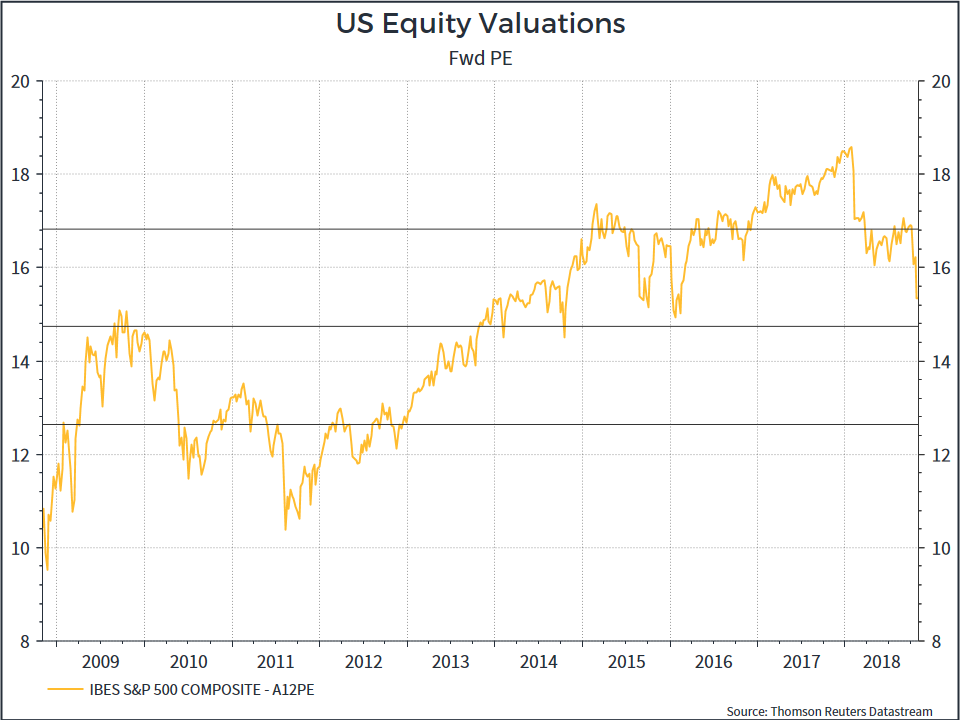

So US equities are trading for less than they were, but does that mean they are cheap? The chart below shows that whilst the US market has had two meaningful sell-offs in 2018, valuations are still sitting above the 10-year average.

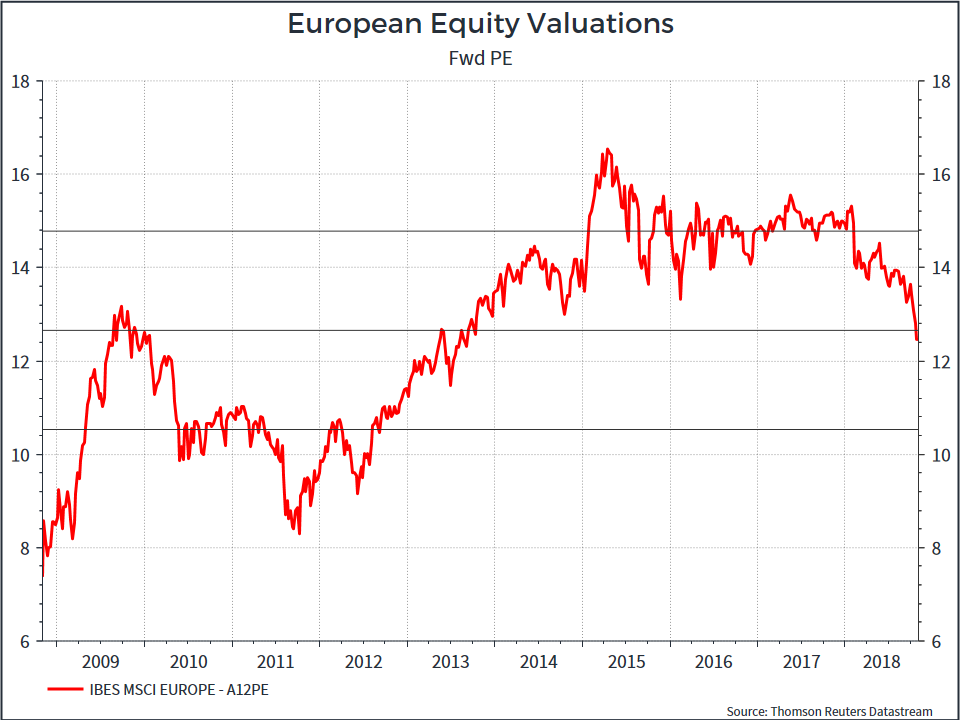

We’re always monitoring the markets to ensure we’re aware of value opportunities when they arise. In Europe, equity valuations are roughly in line with the 10-year average, and are back at 2013 levels.

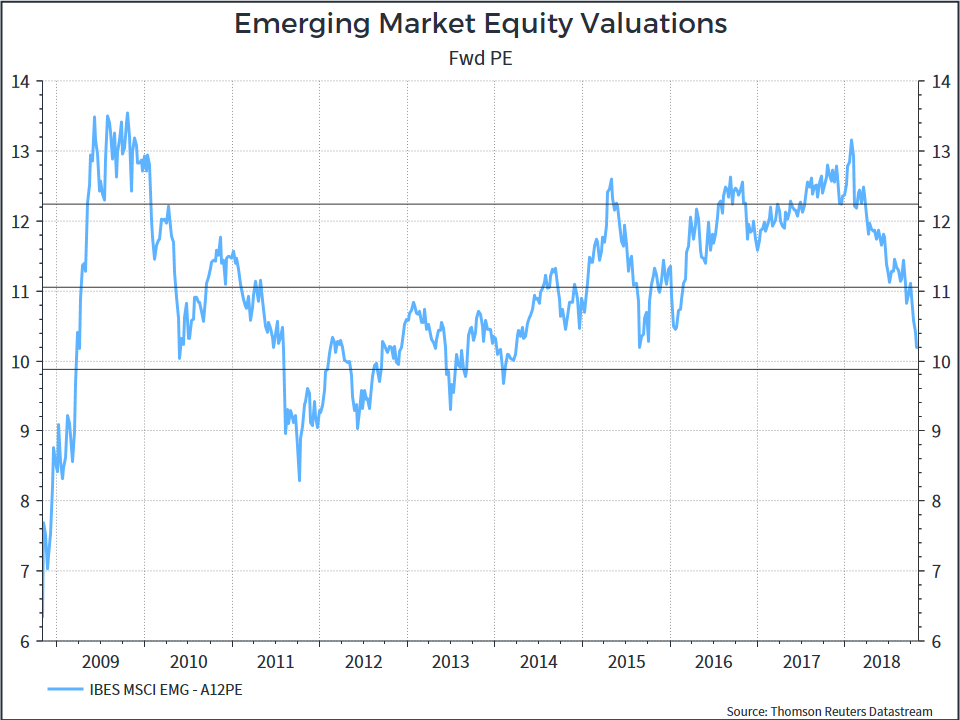

We see better value in Emerging Markets, with equities approaching one standard deviation away from the long-term average PE. Although EM equities have been in this position before, and even lower, there’s more valuation support today then we’ve seen in the past.

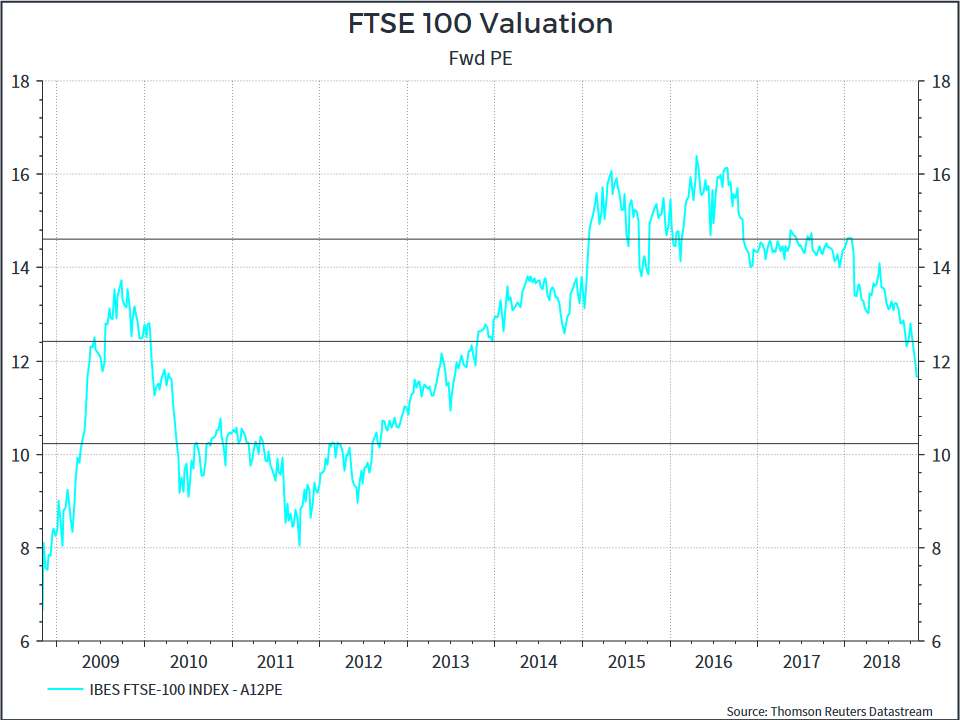

And, finally, the FTSE 100 – which, as we noted above, started to de-rate after the Brexit vote in 2016. Looking at the PE alone, the FTSE doesn’t look super-cheap – only slightly below the long-term average – despite a decent amount of commentary. That’s partly because we’ve used a 10-year average as a comparison.

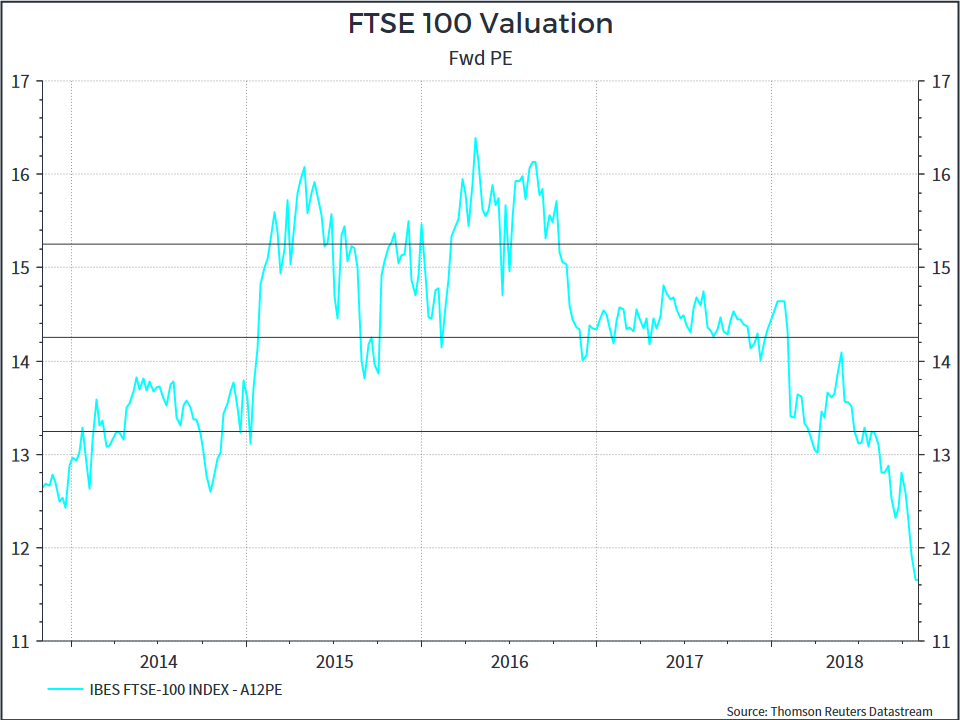

If you were to use a five year average (as in the chart below), the FTSE does begin to look rather cheap versus history.

Valuation is a pretty good signal of long-term returns, which is why it plays a prominent role in our Strategic Asset Allocation process. But it’s less good at predicting short-term returns. At this point we can say that equity valuations look better than they have but in general aren’t very cheap compared to a ten-year history.

As the PE is composed of the Price (which we know) and Earnings (which we estimate), we have to judge how accurate those earnings estimates are. In 2017, expected earnings drifted higher over the course of the year, which helped push equity markets higher.

In 2018, the results are more mixed. US earnings expectations have gone higher, at least for now, while non-US earnings expectations have drifted down.

The chart below captures this. It shows how current year earnings expectations have moved. European and Emerging Market earnings have been steadily downgraded, whilst the US and the UK (more interestingly) have seen upgrades. In the short-term, the case for UK equities looks better with this earnings outlook – even if some of it is probably related to a weaker sterling.

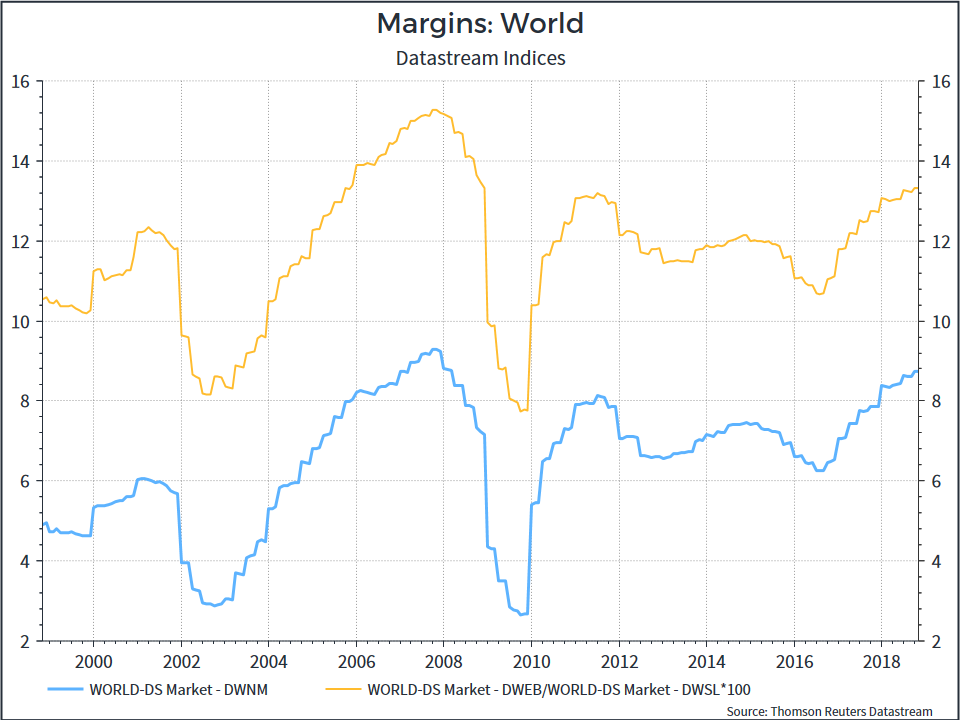

Leaving short-term earnings to one side, the question of corporate profitability is an important one. Much has been written about how recently returns have been skewed towards owners (capital) as a opposed to workers – giving rise to populism.

The chart below tries to put this in some context. It shows corporate margins (operating and net margins) over time. The first thing to note is that margins have been cyclical over the past twenty years. In a recession, we see margins fall. That’s not really surprising.

The second thing is that margins are getting close to the historical peak of 2007. And this, rather than valuations, is probably the bigger risk for equity markets going forward.

What can you take away from this research?

- Global valuations look cheaper, but not cheap.

- Emerging Markets look closest to showing long-term value.

- The UK looks a bit more appealing compared to the last five years, but Brexit colours the debate.

- Earnings revisions have been mixed – with the UK and US looking a bit better.

- Corporate profitability looks high versus history – if we see the global economy weaken that could translate into lower corporate profits, slower growth and further pressure on valuations.

The global backdrop is complex, but we monitor the markets daily on your behalf to ensure your portfolios reflect your investor profile and are positioned in the best way to help you reach your goals.

The Investment Committee was happy with the more conservative positioning of the Moneyfarm model portfolios at the latest rebalancing.

After careful consideration, we decided to use the rebalancing to control the volatility of the portfolios in line with historic levels. We’ve managed portfolio volatility through our overall equity exposure, which we reduced.

It can be tempting to want to change your risk level in response to market volatility, but your investor profile and risk appetite is based on you, not the external environment. By building your portfolio to reflect your appetite for risk, you can help mitigate external risks for effectively when they arise.