This week Fed governor Neel Kashkari caught our attention. Kashkari has developed a reputation as an independent thinker who tries to be as transparent as his role allows. And he’s wondering, out loud, whether the Fed will really need to cut its policy rate this year. Currently, Kashkari isn’t a voting member of the Committee that ultimately makes those decisions, but it’s still worth digging into this a bit more.

Some parts of the argument are familiar. The last two inflation prints in the US have come in higher than expected. Some argue that this is just noise on the downward trend towards the 2% target. Others wonder if it’s a sign, once again, that the battle against inflation in the US hasn’t yet been won to the satisfaction of the Central Bank. Both arguments have some merit, but Central Bankers tend to be a cautious bunch.

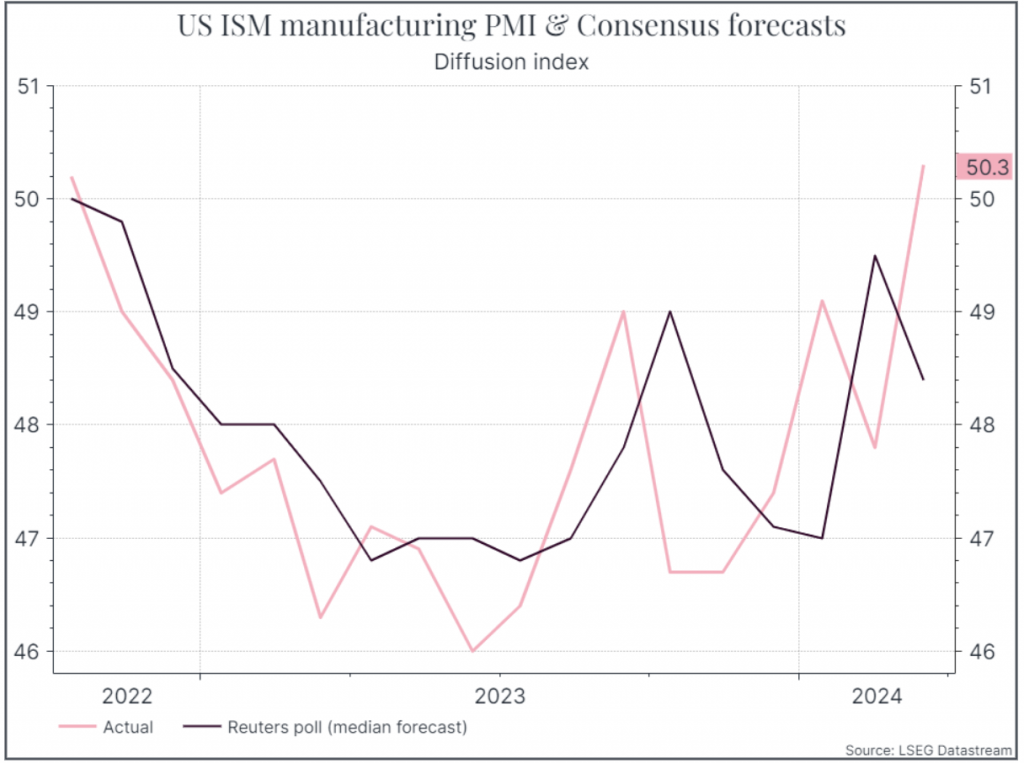

Over the past week, the data gave some comfort to both sides. The Personal Consumption Deflator (yet another measure of inflation) came out roughly in line with expectations, maybe even a bit lower. So that’s good news. But one private sector manufacturing survey (the ISM) gave a more robust picture. First, the survey suggested that the US manufacturing sector is growing, and that the pricing picture for these firms was generally pretty firm (basically, if the index is above 50, it suggests strength).

The chart below shows the ISM manufacturing survey by month, compared to the Reuters consensus of analysts.

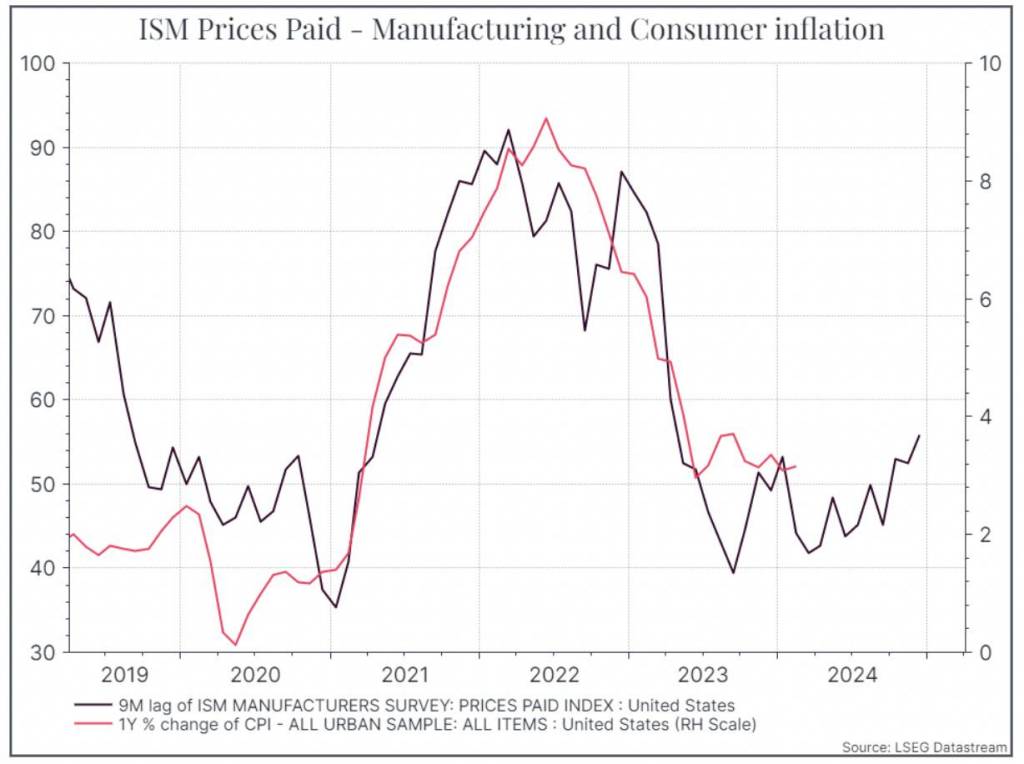

The second chart shows a sub-component of this – a survey on prices paid. As with the overall survey, pricing was firmer than expected last month.

The chart below tries to show why we might care. It compares the prices paid data with US inflation. The chart suggests that ISM prices paid might be a leading indicator for future US inflation (with about a nine-month lag based on this chart). That’s something Central Bankers should at least be mindful of.

While there’s a lot of focus on pricing, in some respects it’s the headline result that is more interesting. Over the past couple of years, the story in Developed Markets has been that manufacturing has been weak, while services have remained strong. But this latest data seems to buck that trend a little.

We’d argue that some of this could be US-specific. There’s been a big policy shift towards increasing domestic investment – partly in response to the supply shortages during COVID and partly as a response to heightened geopolitical tensions with China. The chart below illustrates the impact. It shows spending on private sector manufacturing construction. You’d guess that some of the sharp rise in the past couple of years is a response to government incentives, much to the envy of those in the UK, for instance, bemoaning the lack of investment spending.

Richard Flax: Richard is the Chief Investment Officer at Moneyfarm. He joined the company in 2016. He is responsible for all aspects of portfolio management and portfolio construction. Prior to joining Moneyfarm, Richard worked in London as an equity analyst and portfolio manager at PIMCO and Goldman Sachs Asset Management, and as a fixed-income analyst at Fleming Asset Management. Richard began his career in finance in the mid-1990s in the global economics team at Morgan Stanley in New York. He has a BA from Cambridge University in History, an MA from Johns Hopkins University in International Relations and Economics, and an MBA from Columbia University Graduate School of Business. He is a CFA charterholder.

Richard Flax: Richard is the Chief Investment Officer at Moneyfarm. He joined the company in 2016. He is responsible for all aspects of portfolio management and portfolio construction. Prior to joining Moneyfarm, Richard worked in London as an equity analyst and portfolio manager at PIMCO and Goldman Sachs Asset Management, and as a fixed-income analyst at Fleming Asset Management. Richard began his career in finance in the mid-1990s in the global economics team at Morgan Stanley in New York. He has a BA from Cambridge University in History, an MA from Johns Hopkins University in International Relations and Economics, and an MBA from Columbia University Graduate School of Business. He is a CFA charterholder.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.