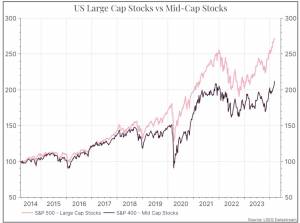

The performance of large US technology stocks has been a focus of attention over the past year or so. Investors frequently ask if they are over-valued or not. The chart below compares US large-capitalisation stocks versus their smaller mid-capitalisation peers.

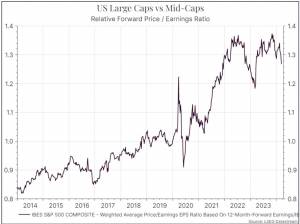

A lot of this performance has been driven by valuation. The chart below shows the relative Price/Earnings ratio of US large caps compared to their smaller peers. We can see that equity investors have awarded large-cap stocks a higher rating over the past decade compared to mid-cap stocks – and the largest tech stocks have been re-rated even more.

This has led to a lot of discussions about whether US equities, and large-cap stocks in particular, are over-valued.

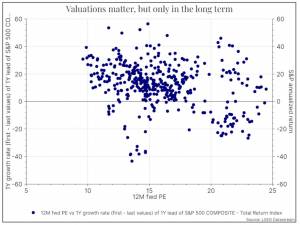

The challenge here is that valuations (reflected in this case by a simple Price/Earnings ratio) don’t always matter. The charts below illustrate the point. The first chart compares the starting valuation of US large-cap stocks (x-axis) against the subsequent one-year return (y-axis) – each dot representing a different observation. The chart suggests that the starting Price/Earnings ratio doesn’t tell you very much about the return over the next twelve months.

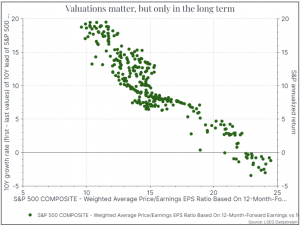

But if you extend the time horizon to ten years, you get a very different picture. The chart below shows the starting Price/Earnings ratio of US large-cap stocks compared to the annualised ten-year return. Now the starting valuation seems to matter much more. It’s no guarantee, but buying US equities at a lower valuation has helped your returns over the long term.

So, what should we conclude? The data suggests that headline valuations aren’t very helpful for timing the market in the short term – we’d argue that it’s a difficult thing to do! But valuations matter much more in the long term. Buying when valuations are low and staying invested has proven a successful combination.

UK GDP: Two-tenths growth, while positive, highlights underlying weakness

Last week’s GDP figures offer a glimmer of hope for the UK economy but expect it to be touted as a massive political talking point. With a growth of 0.2% in January (in line with expectations), the economy has shown signs of emerging from the shadows of recession, however, the growth marks only the second increase in the past seven months, following a 0.1% contraction in December.

It’s noteworthy that sectors like construction, retail, and wholesale have contributed to this growth, showing pockets of resilience within the economy. Yet, it’s crucial for fiscal policy to address underlying issues such as high inflation and sluggish growth, which have been persistent challenges.

The news of this slight rebound in growth comes as a relief, particularly to Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, who has pledged to revitalise the economy. Despite facing challenges such as a workforce crisis, where nearly 9.25 million people of working age are now economically inactive, the expansion in GDP is a positive indicator.

In a game of numbers where growth is either positive or negative by one or two-tenths, the larger story here is the underlying stagnation in the economy, and therefore concerns remain on future output and the economy’s resilience amidst ongoing challenges.

The Chancellor’s recent budget statement suggested optimism about the economy’s trajectory, indicating a turnaround from the slowdown experienced due to measures aimed at curbing inflation. As the UK navigates through these uncertain times, the focus will be on sustaining this momentum and fostering inclusive growth strategies to ensure long-term economic resilience.

Richard Flax: Richard is the Chief Investment Officer at Moneyfarm. He joined the company in 2016. He is responsible for all aspects of portfolio management and portfolio construction. Prior to joining Moneyfarm, Richard worked in London as an equity analyst and portfolio manager at PIMCO and Goldman Sachs Asset Management, and as a fixed-income analyst at Fleming Asset Management. Richard began his career in finance in the mid-1990s in the global economics team at Morgan Stanley in New York. He has a BA from Cambridge University in History, an MA from Johns Hopkins University in International Relations and Economics, and an MBA from Columbia University Graduate School of Business. He is a CFA charterholder.

Richard Flax: Richard is the Chief Investment Officer at Moneyfarm. He joined the company in 2016. He is responsible for all aspects of portfolio management and portfolio construction. Prior to joining Moneyfarm, Richard worked in London as an equity analyst and portfolio manager at PIMCO and Goldman Sachs Asset Management, and as a fixed-income analyst at Fleming Asset Management. Richard began his career in finance in the mid-1990s in the global economics team at Morgan Stanley in New York. He has a BA from Cambridge University in History, an MA from Johns Hopkins University in International Relations and Economics, and an MBA from Columbia University Graduate School of Business. He is a CFA charterholder.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.