As with all investing, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio with Moneyfarm can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Tax treatment depends on your individual circumstances and may be subject to change in the future. If you are unsure investing is the right choice for you, please seek financial advice.

The timing of the first rate cut has become a favourite topic of conversation. With the ECB meeting just around the corner on 7 March and the Fed meeting scheduled in a couple of weeks, on March 19 and 20, let’s try to look at where we are, what the macro data are telling us, and what might be the impact on markets from the action – or inaction – by Central Banks.

Analysts currently expect the first rate cut from both the Fed and the ECB in June, according to recent Reuters polls, but market expectations can move around a lot in response both to incoming data and commentary from Central Bankers.

The message from the data is a bit mixed. Headline inflation is slowly converging back towards the 2% target (the chart below shows the US, the Eurozone and the UK), but it’s not there yet, and the last mile might be the hardest. To emphasise the point, the latest flash CPI figure for the Eurozone for February came in slightly above expectations at 2.6% year-on-year.

The growth story shows a sharper divergence. The chart below shows GDP growth for the US, the UK and the Eurozone. The outperformance of the US is notable. That might argue for the ECB to move sooner.

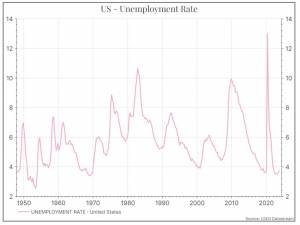

But Central Bankers aren’t really focused on growth. The ECB in particular has a sole focus on price stability, while the Fed has a dual mandate of price stability and full employment. The chart below shows overall US unemployment, which is close to a fifty-year low. It’s a crude metric, but with inflation still above 2% and unemployment at very low levels, you could reasonably ask why the Fed needs to cut rates at all.

The ECB doesn’t have a mandate to look at employment, but if it did, policymakers could make a similar point. Unemployment is low, inflation is above target – why cut rates?

Wage indicators tell a similar story. The chart below shows growth in wages for the average and the lowest-paid cohort of US workers (courtesy of the Atlanta Fed). Wage growth there is decelerating, but is still relatively high versus history and, happily, is running above inflation. The average US worker is, very slowly, regaining some of her lost purchasing power.

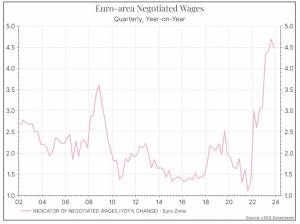

The data is a bit harder to come by in the Eurozone, but one measure of negotiated wages (admittedly only quarterly) also shows pretty robust growth. Neither of these measures argues for a swift cut to rates.

Where does this get us? There are a few points to make. In both the US and the Eurozone inflation and wages tell a similar story – still above target, even if they might be moving in the right direction. The labour market still looks in pretty good health, with low unemployment. In terms of economic growth, the US is an outlier, showing stronger performance than the Eurozone, and most other developed markets. We don’t think that the ECB would have any qualms about cutting rates ahead of the Fed, if there were a good argument for doing so. The challenge, at present, for both Central Banks is that the case for an immediate rate cut isn’t very compelling. That does raise the risk that Central Banks will wait too long to cut, and perhaps damage economic activity, but if the alternative scenario is that inflation might re-accelerate, we think that’s a risk Central Bankers will be prepared to run.

What about the impact on markets? We believe the recent strength in equity markets reflects increasing optimism that we will see a “soft landing” in the global economy – with inflation drifting lower without a significant hit to economic activity. We think the greatest economic risk to that scenario is a stagflationary environment – with sticky inflation and stagnant economic activity. That would likely keep rates higher for longer and put pressure on households and businesses. So far, we don’t see that occurring in the US – where economic activity has proven robust even as inflation has moderated. That should give the US Central Bank some room to manoeuvre in a weaker macro environment. The situation in the Eurozone is a bit more challenging – given the weaker macro data, even if inflation is slowly moving lower. That could prove to be a headwind for European equity markets, but we’d still argue that much of that is already reflected in lower valuations relative to the US.

Richard Flax: Richard is the Chief Investment Officer at Moneyfarm. He joined the company in 2016. He is responsible for all aspects of portfolio management and portfolio construction. Prior to joining Moneyfarm, Richard worked in London as an equity analyst and portfolio manager at PIMCO and Goldman Sachs Asset Management, and as a fixed-income analyst at Fleming Asset Management. Richard began his career in finance in the mid-1990s in the global economics team at Morgan Stanley in New York. He has a BA from Cambridge University in History, an MA from Johns Hopkins University in International Relations and Economics, and an MBA from Columbia University Graduate School of Business. He is a CFA charterholder.

Richard Flax: Richard is the Chief Investment Officer at Moneyfarm. He joined the company in 2016. He is responsible for all aspects of portfolio management and portfolio construction. Prior to joining Moneyfarm, Richard worked in London as an equity analyst and portfolio manager at PIMCO and Goldman Sachs Asset Management, and as a fixed-income analyst at Fleming Asset Management. Richard began his career in finance in the mid-1990s in the global economics team at Morgan Stanley in New York. He has a BA from Cambridge University in History, an MA from Johns Hopkins University in International Relations and Economics, and an MBA from Columbia University Graduate School of Business. He is a CFA charterholder.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.