Please remember that when investing, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio with Moneyfarm can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The views expressed here should not be taken as a recommendation, advice or forecast. If you are unsure investing is the right choice for you, please seek financial advice.

The year 2024 has started on a positive note for markets, although there has been no shortage of alarm bells about risks on the horizon: financial, political, and geopolitical risks. As asset managers, we constantly monitor these risks and will offer some food for thought in this analysis, but at the same time, we are convinced that the case for investing in the markets over the long term remains as strong as ever.

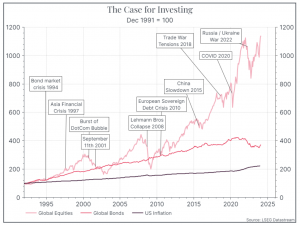

Before we look ahead to 2024, let’s zoom out and take a long-term perspective, including risks – some foreseeable, some completely unexpected – that have actually materialised. Think of the Lehman Brothers default or the COVID crisis. How did the markets react? The chart below shows the performance of global bonds and global equity, compared against US inflation. Financial markets have displayed their long-term resilience in the face of significant challenges. The greatest risk historically, as the chart suggests, was not participating.

With that in mind, let’s turn to 2024.

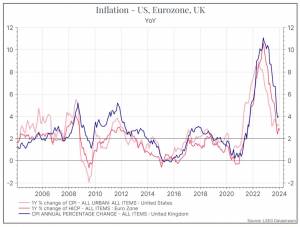

One key risk can probably be summarised as “policymakers get it wrong”. What we really mean is that the attempt to manage a soft landing – bringing down inflation without really hurting growth – proves unsuccessful. That could mean inflation stays higher than expected or that growth proves weaker. In fairness, policymakers appear to have done a decent job – inflation has come down, and growth hasn’t collapsed. That’s particularly true in the US, where growth has been surprisingly strong in 2023.

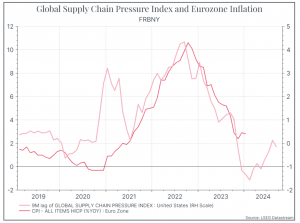

As an aside, some analysts argue that policy-makers, particularly Central Bankers, shouldn’t get too much credit for the decline in inflation and that inflation was really about supply chain pressures. The chart below suggests they might have a point. It shows a measure of global supply chain pressure and Eurozone inflation moving pretty much together over the past five years. We think that argument underplays the role of monetary policy. And we’d guess that if the macro data had been worse in 2023 – higher inflation or much weaker growth – Central Bankers would have taken a lot of the blame! So let’s give them their due.

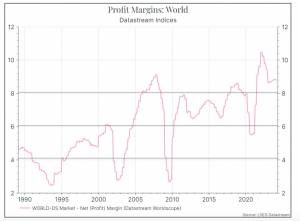

A second area for concern is around corporate profitability and market expectations. Corporate profitability – in aggregate – is currently very high compared to history – as the chart below indicates.

The question is whether or not it will stay as high. Financial market analysts seem to think that margins will stay high and that we are effectively living in a new era of profitability. While the trend has been for higher margins over time, we do see a relationship between inflation and profitability – at least in the US – as the chart below shows. If inflation does fall significantly from here, we might expect to see margins come under pressure.

Politics is another potential source of risk in 2024 – and that might be positive or negative for financial markets. In terms of democratic elections, around half the world’s population will vote this year. Globally, the US election will be a focus of attention. In the UK, we will see an election at some point. In each case, the potential policy impact could be significant, but it will likely take some time for that to appear. More immediately, financial markets will move to reflect expectations of those policies. Guessing which way that will go is a difficult challenge, and probably best avoided in favour of keeping a well-diversified portfolio. We can think back to market moves around the 2016 US election, where concern over the prospect of a Trump victory turned quite quickly into optimism – at least in US equities – over the prospect of corporate tax cuts.

The final point is around geopolitics. Geopolitical risk is on the rise – however you’d like to measure it. The key question here is to what extent it will actually be reflected in financial markets. We’d argue that over the past few years, financial markets have largely ignored geopolitical risk – be it China-Taiwan, Russia-Ukraine or the Middle East. It’s a reminder of the danger of trying to time market sentiment. Looking at the current flashpoints, we can see the impact of the tension in the Red Sea in the supply chain indicators (notably shipping costs). If that persists, we could see it feed into marginally higher inflation over time.

Richard Flax: Richard is the Chief Investment Officer at Moneyfarm. He joined the company in 2016. He is responsible for all aspects of portfolio management and portfolio construction. Prior to joining Moneyfarm, Richard worked in London as an equity analyst and portfolio manager at PIMCO and Goldman Sachs Asset Management, and as a fixed-income analyst at Fleming Asset Management. Richard began his career in finance in the mid-1990s in the global economics team at Morgan Stanley in New York. He has a BA from Cambridge University in History, an MA from Johns Hopkins University in International Relations and Economics, and an MBA from Columbia University Graduate School of Business. He is a CFA charterholder.

Richard Flax: Richard is the Chief Investment Officer at Moneyfarm. He joined the company in 2016. He is responsible for all aspects of portfolio management and portfolio construction. Prior to joining Moneyfarm, Richard worked in London as an equity analyst and portfolio manager at PIMCO and Goldman Sachs Asset Management, and as a fixed-income analyst at Fleming Asset Management. Richard began his career in finance in the mid-1990s in the global economics team at Morgan Stanley in New York. He has a BA from Cambridge University in History, an MA from Johns Hopkins University in International Relations and Economics, and an MBA from Columbia University Graduate School of Business. He is a CFA charterholder.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.