After years of debate, compromise and a fair amount of bluster, the UK and EU have finally reached a new, post-Brexit trade agreement. The details are still fairly vague, but a deal has been struck nonetheless. The document itself is some 1,250 pages long, an agreement that has been ratified by both the UK parliament and the EU. The former passed the deal, which took months to put together, in just a day.

The deal should allow everyone to declare victory – with the possible exception of the British fishing industry, who claim they’ve been sold down the river for the sake of the other 99.2% of British GDP. But, it seems fair to say that this deal, whatever its flaws, is probably better in the short-term than no-deal. It’s also probably worse in trade terms than whatever the UK operated under before – that being the point of the negotiations.

Only time will tell whether or not the UK is able to parlay its new-found freedoms into a better economic outcome in the future, or whether freedom from the European Court of Justice is worth whatever economic price the UK has paid. This is entirely a matter of opinion, again allowing every side to claim victory.

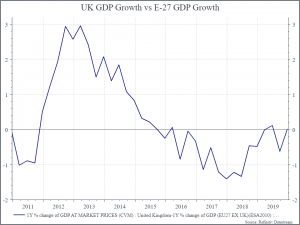

How should we evaluate the success of the deal? Obviously, it’s not straightforward – given the complexities and counterfactuals involved, and that’s even before we consider the significant impact of COVID-19. But in macro terms, we should probably keep things simple – and focus on growth and inflation. The chart below shows UK GDP growth (year-on-year) for the 10 years ending December 2019.

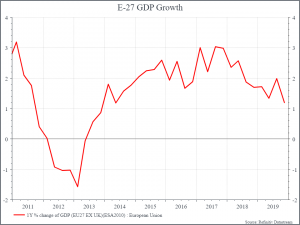

The next chart shows GDP growth for the EU-27 (excluding the UK).

And the final chart shows the difference between the two. The story here is not as clear-cut as you might want. If you look at the last 10 years, UK growth outperformed during the Eurozone crisis but was already weakening prior to the 2016 referendum – although it continued to do so thereafter.

If we look at UK business investment spending, we may see a bit more of an impact. Business investment spending slowed quite sharply after the vote, perhaps reflecting uncertainty about future trading conditions. To the extent that uncertainty has been removed, you might expect/hope to see a recovery in business spending. Or you might have done, prior to COVID. The short and medium-term future of business spending will depend largely on how successful the UK’s vaccine rollout program is, dictating how quickly ‘normal service’ can resume.

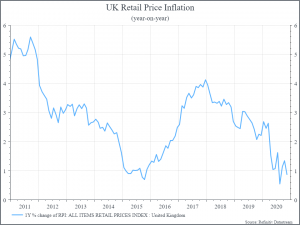

The second consideration – consumer prices – should be easier to map. The chart below shows the year-on-year change in UK retail prices. We can see the fairly sharp increase that followed the referendum in 2016, driven to a large extent by sterling weakness. In 2020, weak demand has driven down inflation in the UK, as it has done elsewhere in Developed economies. If there is disruption, at least in the short-term, from the end of the transition period, you might expect to see this in higher prices. You could also see it in terms of certain goods being unavailable, but that might be tougher to capture in data.

Where does this get us? Not that far, alas. We think that the deal, however ‘thin’ it might be, is better than the disruption that no-deal would have caused. We’d guess that there’ll still be some disruption, given the timing of the deal (just a week before the transition period ends) and the fact that the terms must be somehow worse than the ones the UK previously enjoyed.

So, you might expect to see consumer goods prices pick up in the first half of 2021, even with a deal in place, and we’d guess that growth will be weaker than it would have been. But it also seems likely that the impact of COVID will make evaluating the consequences of the deal quite tricky. We’d expect to see an economic recovery in 2021 – provided the vaccine remains effective and well-distributed – and the impact of the Brexit deal will probably be clouded by that, leaving all sides in the debate able to claim victory.

The long-term impact of Brexit on areas like travel, real estate and education (to name just a few) will take longer to take shape. Much like the trade deal itself, the eventual situation may well end up being acceptable, but worse than the one it replaced. Brexit voters will feel satisfied in some areas and let down in others, much like those who voted against it four years ago. As with everything, this is case of winners and losers – just who those winners and losers are, though, is less clear than we might like.