As the Budget approaches, rumours are swirling once again — and so is the (not entirely unfounded) fearmongering about the creative ways the government might try to raise more tax revenue. The aim, of course, is to plug a fiscal hole whose size depends on which paper you read, but is certainly not insignificant.

One suggestion that was seemingly put to bed, but has come back with meaningful vigour, and is now seen as quite likely, is the desire to cut the cash ISA allowance from £20,000 p.a to £10,000. There are apparently many desired outcomes here, chiefly among them, the desire to get the people of the UK out of cash savings and into investing. But alongside this, we have seen claims that this will boost UK stock markets, improve a declining trend of companies not wanting to “list” in the UK and unlock billions of pounds to be invested in UK companies to drive growth.

Sounds great on paper, but what do we really think?

Getting the nation invested

If you are reading this on our blog and through our newsletter, there is an incredibly high probability that you are already someone who invests. However, you are very much in the minority within the UK, with only 16% of adults having a stocks and shares ISA.

We do believe that it is important to get more people invested and in fact it is one of our key missions. The key reason is below.

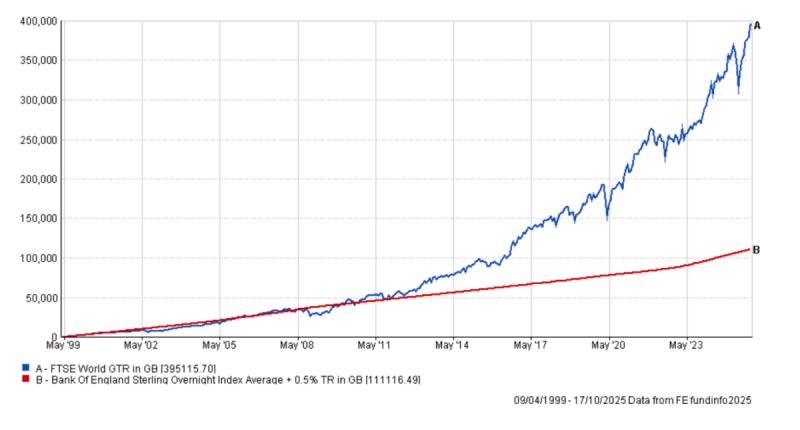

Above you can see the returns had you put £250 a month into a cash ISA (Sonia overnight rate + 0.5% over the period, red line) or Stocks and shares ISA (invested into the FTSE all-world index over the period, blue line) over the period since the introduction of the ISA, April 1999 until 17/10/2025.

Past performance, of course, is no guarantee of future performance. But here we haven’t cherry-picked the best investments over the period, simply looked at the global stock market in general. It’s worth noting that this period began at the height of the dot-com bubble and spans the global financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and every other major market downturn since.

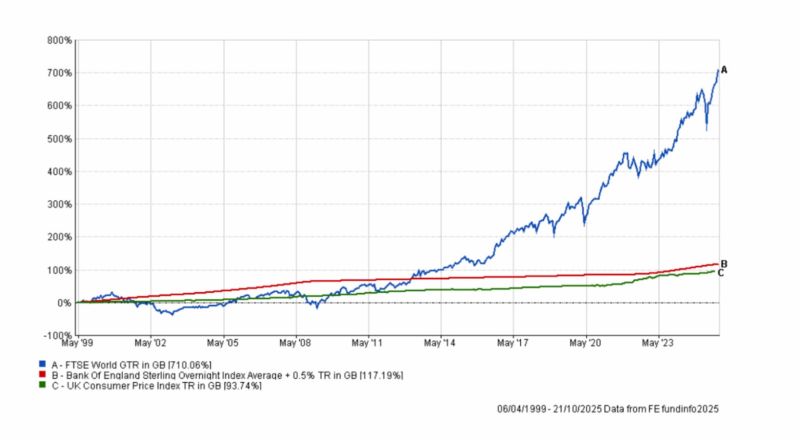

Looking beyond performance alone, comparing the returns of the cash and stocks & shares ISAs with inflation over the same period (green line) offers useful perspective.

We see that the cash savings only just come slightly above inflation, meaning savers would have been essentially treading water over that period.

So we whole-heartedly agree with the idea that people of the UK should be investing more.

Is this the right way to do it?

If you’re wondering whether we think this is the best way to get people to invest, the short answer is no. Ultimately, I doubt the main reason people don’t invest is the tax benefit of cash ISAs. For many years (after ‘08), many cash ISAs didn’t generate enough return to be taxable.

The real issue lies in education. Many people don’t understand financial markets and see them as scary things which are not tangible – and understandably so. There is no education on the topic, generally, and you can’t expect someone with no knowledge or experience of financial markets to suddenly jump into putting significant amounts of savings into something that they don’t understand. Many people don’t even know that their workplace pension is invested and are shocked when they find out.

The government needs to help to educate people about the risks and rewards of investing first, before suddenly cutting off access to other options. The ‘how’ we will leave to them – we are already trying to do our best (for those unfamiliar with our blog, I would recommend a visit).

So – what would happen?

Putting predictions in black and white is always a dangerous game, particularly in this industry, but I’ll put my head above the parapet.

You may see a small uptick in the number of stocks & shares accounts being opened as more people ‘give it a go’, but it’s unlikely there will be a huge influx of billions (£614bn excess cash by Barclays’ estimate) heading into Stocks and Shares ISAs.

Most likely, people who only feel comfortable in cash, will opt to simply open non-ISA savings accounts and end up paying a good chunk of their interest in income tax (the more skeptical amongst you might suggest this is the actual end goal).

Another thing is that you would likely see a huge upsurge in money-market funds as stocks and shares ISAs. Products like our very own Liquidity+, which buys a diversified set of extremely low-risk, short-term bonds which generate interest that basically tracks the Bank of England base rate, will suddenly be rebranded with a name as close as “Cash-like ISA” as the FCA will allow.

These products are certainly an interesting alternative and should this change occur, you will likely hear more from us about ours.

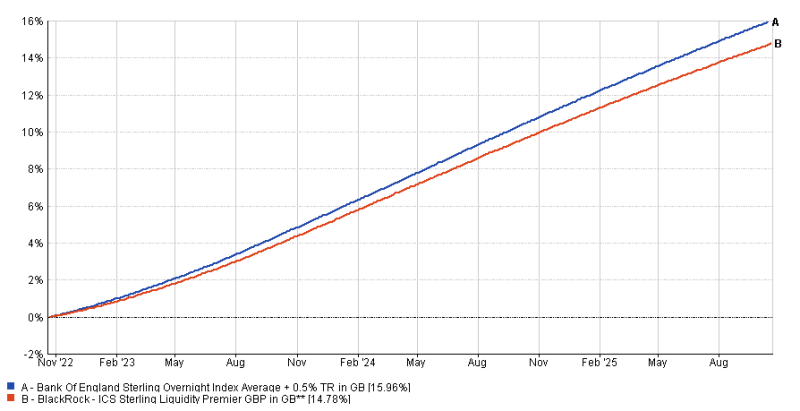

As you can see from the chart below, the return and risk profile of the money-market fund (red line) is very similar to that of cash (blue line), particularly as 0.5% above base rate is quite generous for a Cash ISA option. Here we are looking at SONIA + 0.5% vs a Blackrock QMMF from 22nd October 2022 to 22nd October 2025. However, it can be wrapped in a Stocks and Shares ISA. So for those looking for lower risk, but wanting to take the full £20,000 allowance in very low risk (rightly or wrongly) would still have the option to do so.

So, I would imagine that you would see a surge in popularity in these products, as an alternative to a cash ISA, which is perhaps not the outcome that the Treasury were hoping for. Particularly if the industry can articulately, but simply, explain the risks and return profile of money-market funds.

Would it even improve the UK markets?

Assuming my suggestions above don’t occur, and actually money floods into Stocks and Shares ISAs, what would the knock-on effects be? Firstly we do believe that over the long term it would increase people’s wealth – as long as people make investments that are right for their risk appetite and time horizon.

However, with no other changes, I am dubious that you would see a meaningful impact for the UK economy or stock markets. For example, with Moneyfarm’s 100% equity portfolio only 14% is invested into UK equities, most of which are companies in the FTSE 100 which make their money overseas.

I would suggest we are not alone. As the UK markets have massively underperformed other global markets, most people would likely invest overseas, whether in US ETFs and stocks, Emerging Markets or Japan. The options are endless.

There are rumours again of the ‘British ISA’ , an idea first floated under the previous Conservative government, which was scrapped. This is an idea that a certain amount of the allowance – not clear whether it’s an extra allowance as originally suggested or just part of the existing allowance – must be invested into UK markets.

It’s an interesting idea – it would certainly solve for money being invested abroad. But again, I’m not sold. Firstly, it’s unclear whether the investment would have to be in equities – and it shouldn’t be if that’s not suitable for the investor. Forcing people to buy gilts instead of other bonds wouldn’t deliver much growth; at best, it might synthetically lower the government’s cost of borrowing by boosting demand for its debt. Would UK listed money-market funds count – if so – you might see the same effect as suggested above. So this part is not clear.

Even if it does have to go into UK equities, if you buy a FTSE 100 ETF, none of that money actually reaches Tesco. You are buying it off another investor, so it wouldn’t really allow the companies to get money to stimulate further growth. You could argue, forcing money into UK stock markets could synthetically push up the multiples (particularly prices) of the market in general making it more appealing for new companies to list. But again, if people are putting in £5,000 allowances, would it move a £2.3 trillion market enough? I’m not sure.

There could be some interesting use cases, where money is used to directly invest in start up ventures or similar growth/unlisted companies – where the money goes directly to the end company. But these investments can be very risky, so there needs to be some serious oversight and guardrails on such a policy.

So again, the idea is a nice one, but there are so many moving parts and it needs a huge amount of structuring to make sure that the desired outcomes are achieved.

I haven’t even started talking about whether this is actually a good thing for the investor themselves…

What should you do as a result?

As you can see, this is not a policy that I believe will have the desired outcomes. Of course, my opinion carries little weight within the walls of 11 Downing Street – and there’s every chance it will go ahead regardless. So what should you do?

Our position on this doesn’t really change. Cash is a fantastic savings vehicle for short-term rainy day funds, or if you plan to use the money in the short term (up to 18 months to 2 years). So, if those needs are already fulfilled and you have a plan in place, then rushing to fill your cash ISA allowance before you might lose it could be quite reactive.

The key is to have a long-term plan and stick to it. Know how much you need in your short-term reserve and then work out what your other goals are. Then structure your savings based on those goals with longer-term, further away goals, given the best chance to grow in higher risk (still diversified and matching your risk level) investments. Then shorter-term, closer goals in lower risk assets, including mixtures of equities and bonds, or bonds and cash.

If you are someone who generally puts more than £10,000 into a cash ISA each year as it’s the appropriate vehicle for your goals, then do some research into some alternatives, such as money-market funds, these will still be available, I imagine, as an option.

But most of all, speak to us. Our friendly and professional team is on hand to discuss your situation and can guide you in making a decision and understanding your options. You can schedule a phone appointment or call us on 0800 433 4574 to get straight through to our team.

As always with these pre-budget rumours, we could actually be worrying for nothing.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.