Have you ever told yourself you would run a marathon? Start eating healthier?

Or perhaps finish a book every week?

Well, if your running shoes are in the back of your closet after being worn once, your social media is full of stunning healthy recipes that you’ve yet to try out, and your book has been sitting there for weeks – half-read and with a layer of dust – you are definitely not alone.

While research has attributed goal attainment to positive qualities, such as greater wellbeing, self-esteem and overall success, the sad reality shows us that up to 40% of people tend not to set goals for themselves. Of the remaining 60% who do, around 92% fail to achieve their objectives – leaving only an exclusive 8% of people to be identified as the successful ‘goal-achievers’.

If you’ve ever come across a behavioural science article on goal attainment, you might already be familiar with a long list of reasons for why our limited brains have trouble sticking to their own objectives. Or you might know why, as irrational beings, our actions tend to not always reflect our intentions.

However, there’s good news – solutions exist.

In this series of articles, we’ve decided to focus on one behavioural obstacle that could be holding you back from reaching your goals: present bias. We’ll give an overview of what this means and provide you with a number of insights from behavioural science that can transform you into a goal achiever, making that small 8% pool that little bit bigger.

What is present bias?

Present bias refers to the tendency we have as human beings to place greater emphasis on the here-and-now, prioritising our current individual needs and desires at the expense of our future ones.

Present bias is strongly related to an analogous concept within behavioural science, known as hyperbolic discounting, where we tend to place greater value on immediate payoffs than we do on future ones.

This applies even when we expect a greater value in the future than in the present – i.e. we would rather receive £5 now than £10 in a month’s time. It also applies when our present benefits can actually lead to future costs (i.e. we might choose to enjoy an extra drink this evening, even though we know we will regret it tomorrow).

Why does present bias occur?

Researchers have established two leading explanations as to why, as human beings, we are typically subject to present bias.

Firstly, we tend to make affective forecasting errors. What this essentially means is that we often misjudge our future feelings, both in terms of valence (positive vs. negative) and intensity.

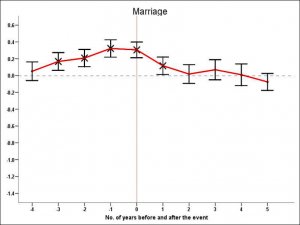

The graph below shows the results of an interesting analysis conducted by researchers Andrew E. Clark, Ed Diener and Yannis Georgellis of the German Socio-Economic panel, during which people were asked to rate their current satisfaction at different points in their lives.

This shows us that, while people typically get married expecting a lifetime of happiness, this feeling gradually fades over time. While bleak, this might explain why people’s present choices often fail to match up with their future emotions.

Wishful thinking

Researchers have also attributed present bias to a second phenomenon – optimism bias.

Optimism bias refers to the tendency we have as human beings to overestimate how positive our personal futures will be. The most common examples of this are thinking we will live longer than average, pursuing our dream careers, or expecting social support to cover our costs during retirement.

Neuroscientist Tali Sharot explains that this kind of positivity bias is necessary to human development, allowing us to live our day-to-day lives normally and with relative peace of mind. As Sharot points out, most of us would be unable to function properly knowing that, sooner or later, something bad is going to happen.

So, while optimism bias is necessary for peaceful living and goal pursuit, there are certain areas in which too much optimism may actually cost us more than we’d like. A clear example that researchers often point to is retirement savings. Excessive optimism in this instance has, in fact, been identified as one of the main reasons people fail to effectively plan for retirement and save enough to live as they wish. Recent estimates suggest that up to one in three Brits have not saved enough for their pensions.

Therefore, it’s important to find a middle ground – to hold a level of optimism that enables exploration while allowing for clear judgement of your future situation.

Now that you’re familiar with one of the biggest obstacles that may be keeping you from achieving your goals, as behavioural scientists we know that just telling you about it won’t actually help make you a goal achiever.

In our next few articles, we will provide you with some of the tools behavioural science can offer you to take charge of your choices today and get one step closer to achieving your long term goals.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.