What are we talking about? Active management versus passive index-tracking. It’s an old debate, but we saw some interesting data from S&P, a global data provider, that seemed worth considering.

Where do we stand? We have a few thoughts.

First, we’ve generally believed that the debate between active and passive is a bit overblown. We ultimately care about the return our clients receive after all the fees (the net return) – whether that’s generated by active managers or passive indexing. We’re more interested in the distinction between high-cost and low-cost alternatives, since we think that costs are one part of investing that should be clear at the start.That said, for most retail investors, actively managed products generally have higher fees than passive alternatives, but we wouldn’t always reject actively-managed products out-of-hand.

Second, and a bit more philosophically, we think that most decisions involve a choice – even selecting a market-cap weighted index ETF – which we think is what most people would regard as a passive product. Picking stocks (or more technically, taking idiosyncratic risk) is not the only way of expressing an active view about financial markets.

Third, we generally think that outperforming an index by more than your fees isn’t very easy to do. Doing it consistently is even more difficult. Finding a manager who’ll be able to do that (before he / she has done it) is also a challenge.

And the third point brings us to SPIVA: SPIVA stands for S&P Indexes Versus Active funds. It’s research from S&P that looks at the performance of mutual funds compared to S&P benchmarks. It’s publicly available should you wish to dig into the reports in more detail. Generally SPIVA reports don’t make happy reading for active managers. The headlines (on their website) say that in the US, only 33% of US large cap managers outperformed the S&P 500 over the three years to June 30th 2021. In Europe, only 28% of European equity managers outperformed the S&P Europe 350 Index. Typically, the further out you go, the smaller the percentage that outperforms.

Those headline numbers are worth repeating, but they’re not particularly new – and the trend into passive products over the past decade suggests the data has been well-digested.

More interesting stuff: There were a few points in the data that are worth highlighting. The table below shows the percentage of sterling-denominated funds that underperformed their S&P benchmark (we don’t have a good reason why sterling-denominated European equity funds seem to have fared better than their euro-denominated equivalents). The basic story is the same – for European equities, global equities, US and Emerging Markets – mutual funds have struggled. In the UK, however, mutual funds have fared relatively well over the past five years – with around 60% of them outperforming the S&P UK index.

There’s an interesting contrast here. Active managers generally argue that they should outperform when markets are less efficient, when stocks aren’t maybe so closely followed. That’s why the US is usually regarded as a difficult place to beat a benchmark. But the UK should, if anything, be an even tougher place to outperform. There are lots of analysts looking at stocks, and there aren’t actually that many stocks to look at. Very crudely, the US has 500 stocks in its standard benchmark; the UK has only 100! Yet, on this data, active managers in the UK seem to have done better – (we must confess that we don’t have a good answer to this currently!). On the flip side, this logic would suggest that Emerging Markets – generally regarded as less-well covered by financial analysts – should see active managers do better. Again, the long-term data doesn’t support that view, with the index seeming to beat the majority of EM equity managers.

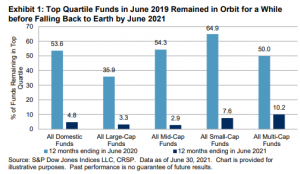

What about persistence? The latest report from SPIVA on US equities has some interesting things to say about persistence – the likelihood that a strong-performing fund will continue to do well. The chart below illustrates the challenges. It basically says that a decent percentage of first-quartile funds in the year to June 2019 continued to be first quartile funds in the following 12-months (53.6% of them), but only 4.8% of them were first quartile funds again in the third year. In large cap US equities (measured against the S&P 500) only 12% of funds outperformed for three consecutive years (Year to June 2019, 2020, 2021). An active manager might reasonably argue that they don’t expect to outperform every year, and the long-term performance is what matters. That’s fair, but the long-term results also show that persistent outperformance is a challenge.

What about some caveats? There are always a few caveats. First, this is one dataset. We might be able to find data that contradicts it (happy to be shown it). Second, indices don’t include fees while passive products do, even if the fees are low. That’s fair, and it matters more the longer you’re invested. But you can get S&P 500 exposure for below 10 bps per year, so we’d be tempted to say that the difference should be pretty small at least in the US (or the UK). Third, maybe not all funds use S&P indices as their benchmark. In Emerging Market equities, for instance, MSCI is a popular benchmark provider. But comparing MSCI and S&P/IFCI seems to suggest that the cumulative difference between the two of them is also fairly small. Finally, the performance analysis is equally-weighted by fund. So it gives the same weight to a small, underperforming fund as it does to a large, potentially outperforming one. That could also be a fair criticism. The other side of that is that investors often only enter a fund after a period of strong outperformance, so the investors realised experience might also be different from that of even a successful fund.

Where does this get us? There are a few points worth making. First, indices aren’t boring. This data suggests that the index in most equity regions does better than the majority of active funds over the medium to long term. That seems like a strategy worth considering! Second, it’s a reminder – as we said at the start – that persistently outperforming an index, after fees, is tough. And selecting managers who can do that is also pretty difficult. To do well with this approach, you need to get a lot of decisions right.