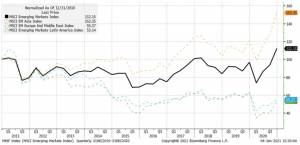

The last decade has not been particularly kind to emerging markets. The performance of this particular index, which is now made up of an extremely diverse group of countries, has remained largely stagnant over the past 10 years.

What are the reasons for this stagnation? And what are the prospects for this particular asset class in the post-pandemic world?

A decade of lost growth

As you can see from the chart, the main drivers of emerging stock prices have stopped growing since 2008, which has had a negative impact on the value of equity. The performance of raw materials – one of the main sources of economic support for many countries included in the list – was also negative.

The blue line represents the evolution of GDP in the index excluding China, the black line the volume of outward flows, while the orange line represents the value of the S&P GSCI index on raw materials.

This disappointing performance should be viewed within the context of the structural slowdown in the growth rate of the Chinese economy. This is a factor that has hurt the Asian giant’s equities. The trade situation between emerging countries has certainly not helped either, given that the only growth seen in this sense is linked to Chinese development.

The divergence between geographical areas

To get a clearer picture of what we mean we talk about the emerging markets index, we should examine the geographies individually. Over the last 10 years, we’ve seen a divergence between the performance of Asia and that of European emerging markets – dominated by Russia, which has suffered since the collapse in the price of oil – and South America.

This disparity in performance became even more pronounced in 2020. Asian economies handled the Covid-19 crisis in a relatively orderly fashion, while the maturity of these economies makes them more prepared to handle a global recession.

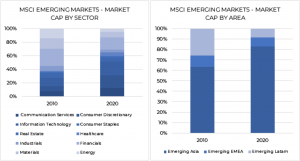

These price dynamics have been accompanied by significant changes in the actual composition of the ‘emerging’ index. Indeed, it’s a label that is now arguably too diverse to properly represent the reality for a lot of the economies it covers. The MSCI Emerging Markets Index is now more than 80% made up by Asian countries.

In terms of sectors, traditional industries like finance, materials and energy, now represent only 25% of the index. This is down from almost 60% in 2010, yet it’s still a key reason that these countries are grouped together into a single asset class. In a way, the MSCI emerging index is similar to that of US equities, with a few key companies making the difference. Alibaba, Tencent, Taiwan Semiconductor and Samsung account for 23% of the entire index.

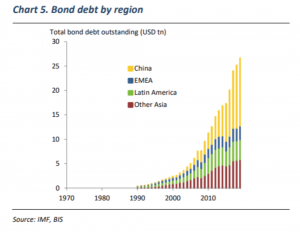

The bond landscape also appears to have changed considerably. In the 90s, debt issues came mainly from Latin American countries, while the last 15 years has seen China and Asia more generally assume a dominant share in this market.

What are the prospects for this asset class?

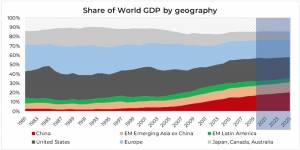

As with many aspects of our life, Covid has accelerated a number of dynamics that have already been underway for some time. In the coming years, it’s reasonable to expect that the lion’s share of global GDP growth will come from Asian countries, with China continuing to expand its political and economic weight.

Short-term prospects

2021 is likely to see a significant rebound in GDP. This is, potentially, a boon for the prospects of this asset class, particularly in the case of the Asian markets. The factors most likely to benefit performance in the short term are:

- A weak dollar, which historically means financial stability and economic performance in many of these countries.

- Commodities, which could be well placed to see a positive rebound in 2021.

- Good management of the pandemic in the most important countries of the index (Taiwan, South Korea, China) and therefore a faster economic rebound.

- Economic recovery in developed countries more generally.

Long-term challenges

If we broaden our horizons for a moment, we can’t ignore some key political issues – these are factors which will define the narrative of global politics in the coming decades. China has, for some time, been taking clear steps to construct its own regional (and global) hegemony. The medium to long-term objective of the project is, seemingly, to increasingly free itself from the Western political and economic system.

On the other hand, the US has viewed the growth of China with increasing mistrust. Under Donald Trump’s administration, it has taken defensive countermeasures to limit the access of Chinese companies – particularly technological ones. Much has been said about Trump’s rhetoric around trade relations with China and how a Joe Biden administration could reopen dialogue.

Anyone expecting a complete change of approach from the US, though, is likely to be left wanting. The establishment of a new relationship with China is chief among the US’ international political concerns, and we are not expecting a wholesale change of rhetoric. What is clear, however, is that US-China relations will remain a central political issue in the coming decades and one that will have a profound effect on the Chinese market.

Biden has some sensitive issues to handle in the early stages of his presidency – one of which is deciding the fate of the various economic sanctions imposed on China by the Trump administration. These include the ban on Chinese telecom companies on the New York Stock Exchange, the heavy sanctions against Huawei and the restriction of payments to Chinese apps.

The president-elect will also have to take a stand on the Hong Kong crisis, which is becoming increasingly difficult to ignore. Biden is unlikely to change the general direction of Trump’s approach, rather he may attempt a multilateral approach in managing what is perceived as the ‘Chinese threat’. This means involving allied countries by opening doors to Chinese diplomacy – the ambitious trade agreement signed last year with China, Japan and Australia among the main signatories is proof of this.

In short, in pursuing hegemonic policies, the two superpowers will make economic decisions and concessions that could determine the fate of entire sectors in the years to come. As far as investors are concerned, there is no doubt that China represents an issue to be solved. What it also represents is an increasingly mature economy, home to some of the world’s most advanced and promising companies.

However, the accessibility of this market seems increasingly linked to the long-term resolution of international tensions. China has also been the example in recent years of how equity performance and economic growth do not go hand in hand. The future is bound to come with new challenges and this will be an area for investors to keep an eye on.

The wider picture

If we widen the lens again and consider the rest of the emerging world, the most relevant news is the signing of RCEP – the trade agreement that aims to strengthen economic relations between 15 countries in the Asia-Pacific region. The deal, potentially the largest ever, affects more than 2 billion people with a combined GDP of around $26 billion. As we mentioned earlier, the inability for effective trade between emerging countries held back performance, and an agreement of this type could open up new business opportunities.

Of course, the issues that have affected emerging markets over the past decade will need to be resolved. Chinese and Indian growth slowing down, stable or declining exports, a kind of deglobalisation and the poor performance of raw materials – these are areas to tackle if the index is to succeed.

As a wealth manager, we are weighing up how useful it actually is to consider this index as a unique asset class. As managers, then, we have to keep the diversity and complexity of the economic group in mind when talking about it. We are, however, convinced that this block of countries will play an increasingly important role in multi-asset portfolios, especially now that traditional geographies seem to offer limited expected returns.