The US administration continues in its efforts to increase its influence over the US Federal Reserve. It is currently looking to dismiss one of the Fed governors based on allegations of potential mortgage fraud from 2021. In theory the Federal Reserve is independent of political influence – it answers primarily to Congress and its governors cannot be dismissed except for “just cause”. While the details of the case aren’t immediately relevant, it seems clear that the administration is actively looking for levers to achieve its goals. We wanted to think through some of the possible implications.

Why central bank independence matter

On the subject of Central Bank independence, it has generally been held to be a positive development. In theory, it’s a good thing to have policy-makers who aren’t quite so beholden to the electoral cycle and public opinion. But it’s also worth remembering that hasn’t always been the case. In the UK, for instance, the Bank of England only became independent in 1997, at least regarding monetary policy.

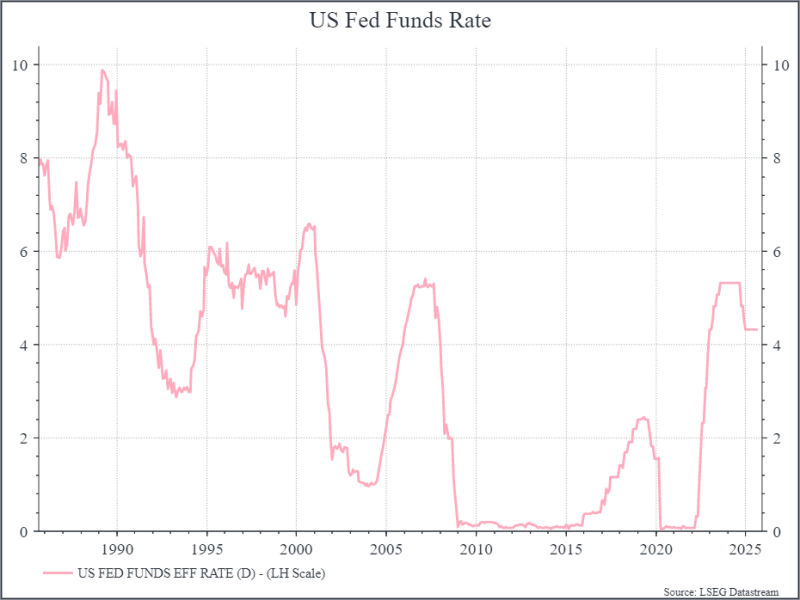

When it comes to Central Banks, the focus of attention is usually on the policy interest rate. In the US, the President and the Treasury secretary have argued that US policy rates are too high and should come down. In theory they can’t make that happen immediately – it’s a matter for the voting members of the Federal Reserve, but they can clearly put pressure on those individuals by their statements. This isn’t a unique situation – a number of previous Presidents have tried to put pressure on Fed officials. But this administration seems overtly much more committed to bringing monetary policy under its control.

Beyond rates: Fed’s balance sheet

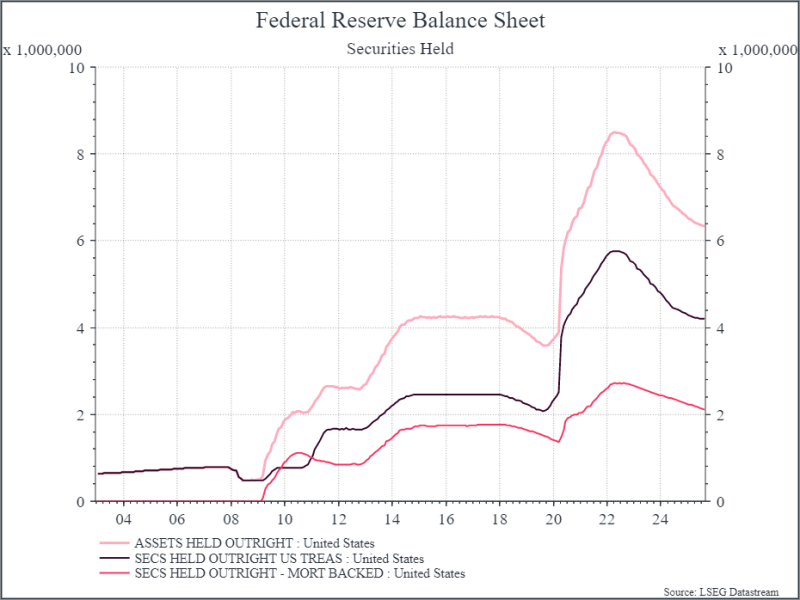

It’s important to note that Fed officials don’t just set interest rates. In recent years, they have also used the Fed balance sheet to influence monetary conditions (so-called Quantitative Easing, or QE) – by buying US treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. As a number of commentators have noted – see John Authers at Bloomberg – this might be the real goal for the administration. Quantitative Easing can blur the lines between monetary and fiscal policy.

Just for some context: after the Great financial crisis of 2008, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates basically to zero (see chart below). To provide additional stimulus, the Fed started buying US Treasury bonds, agency bonds and some corporate bonds – effectively injecting more money into the financial system. Other central banks followed a similar approach. Many argued that this was effectively fiscal policy, funding government spending by just printing more money, and would create distortions in the economy. Opinion is divided on how effective the policy has been in supporting the economy.

The chart below shows the evolution of the Feds balance sheet over time. We can see that the Fed increased its holdings of Treasuries and mortgage bonds during the crisis and then held it fairly steady. Once Covid hit, the Fed followed the same playbook – cutting rates to zero and aggressively buying government bonds to support fiscal spending. Since 2022, the Fed has gradually been reducing its holdings, largely by not reinvesting in new Treasuries as older bonds mature.

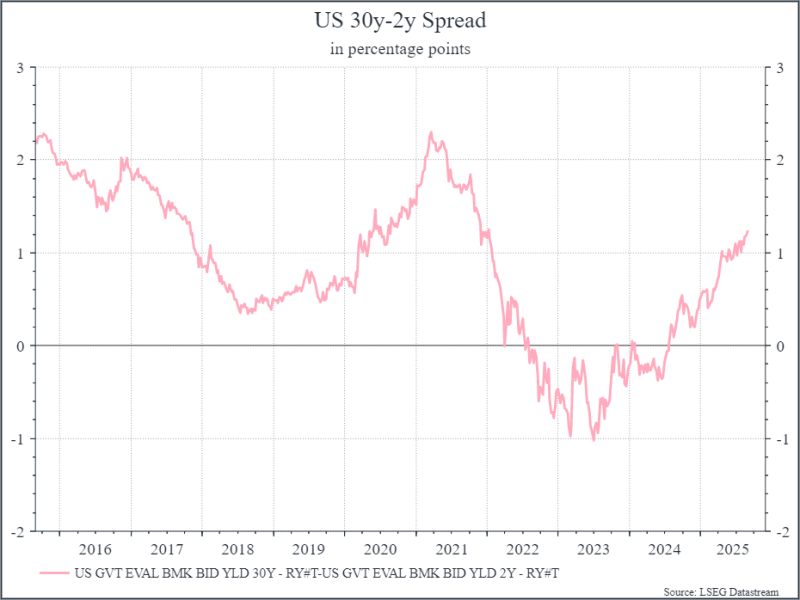

So much for history. The current administration would like policy interest rates to come down (like most administrations), but they’d also like to see the interest rates on longer-dated bonds come down as well. That’s not so easy. The policy rate can have a significant impact on short-term rates, but much less of an impact on the rates for, say, 30-year bonds – which has the most impact on mortgage rates in the broader economy. It’s possible that the lower the policy rate, the more concerned investors will be about long-term inflation and as a result they may demand higher rates on longer-dated bonds.

The chart below illustrates the point. It shows the difference in the yield on a US 30-year Treasury bond and a two-year Treasury. We’ve seen it move steadily higher over the past year or so – albeit from what we’d argue was an abnormally low level in 2022 and 2023.

So, the point of all this is if you think long-term interest rates are too high, having control of policy rates doesn’t necessarily solve the problem. Being able to buy longer-dated bonds might help bring those down – but it’s not certain – and that’s something policy-makers could consider.

Let’s think about what could happen if the administration does manage to exert greater control of the Fed – most likely by appointing governors more aligned with their views. Policy rates would likely be lower and the Fed would potentially restart buying more Treasury bonds. What could the impact be? There are various estimates from the financial crisis experience, but it could translate into around 100 bps impact on Treasury yields.

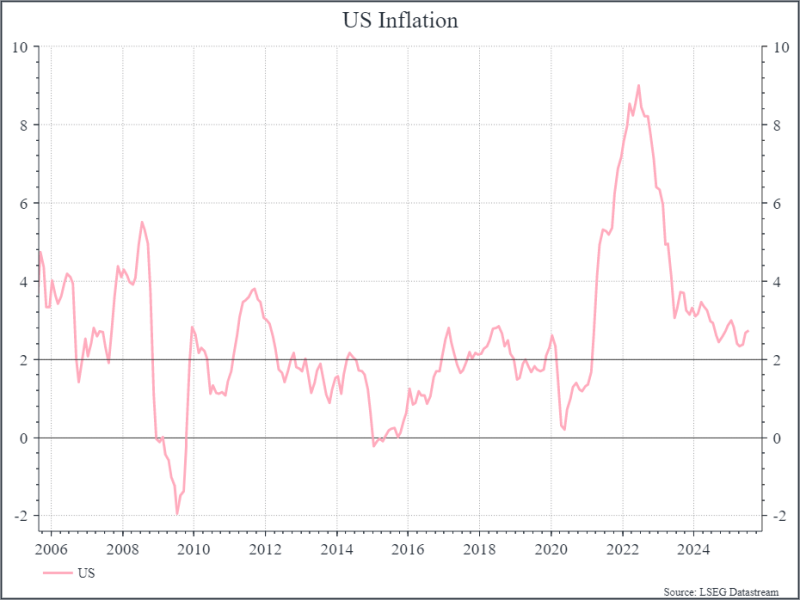

Inevitably, it’s not quite that simple. A combination of lower rates and more Quantitative easing could push up inflation – leaving market buyers of Treasuries looking for a higher yield. Whether you think it will or not depends a lot on your view of inflation. During the decade after the financial crisis, inflation was pretty subdued. But that’s not where we are today. The chart below shows US inflation. We’re close to the 2% level that Developed Market central banks typically target, but still away from it – with the potential for tariff-driven inflation still to come.

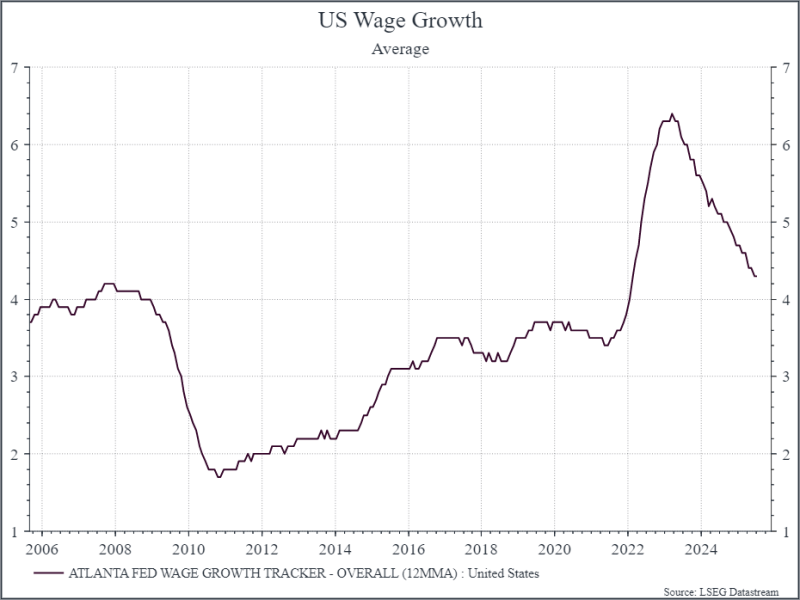

Similarly US wage growth, as estimated by the Atlanta Fed, remains pretty robust at above 4% year on year. That might suggest that easier financial conditions could feed into inflation fairly quickly.

Finally, if investors and households don’t expect the Fed to take steps to fight higher inflation (by raising rates), they’d begin to assume sustainably higher inflation in the future – with a knock-on effect on wage demands and bond yields.

Where does this get us? It’s too soon to tell where we’ll end up on US monetary policy, but it’s reasonable to think that the administration will be able to shape the Fed in its preferred image – with a more dovish set of policy-makers. Given our view that inflation in the US could prove quite sticky – i.e. getting to 2% will be tough – we think that a more dovish policy would have a negative impact on inflation going forward.

Implications for bond and equity markets

What does it mean for markets? Normally that inflation outlook would argue against buying longer-duration bonds in the US, but that calculation gets more complicated if we did see the Central Bank start buying bonds again and if the gap in yield between short-dated and long-dated bonds continues to widen. On balance, though, we’re more likely to err on the side of caution in this scenario and stay away from longer-dated US bonds.

On the equity side, the situation is more complicated. Again, we think a lot depends on where inflation could settle. It might be easy to say that 20% annual inflation wouldn’t be great for equities, but if inflation is 4-5%, the data is a bit less clear. In that scenario, of higher nominal GDP growth, well-run businesses could actually flourish – controlling their costs effectively and passing on higher prices to customers. At some point, that becomes socially unacceptable, but in the interim, companies could see their profit growth accelerate. It’s not just about profit growth, though. Equity valuations could suffer in a higher inflation regime. Here again, the historical experience isn’t super clear. Equity multiples do seem to fall at very high inflation rates, but with mid-single digit inflation, the relationship isn’t particularly clear.

As we continue to navigate the market environment, what does seem clear is that we need to continue to consider a wider range of policy scenarios, particularly in the US, than we did a year ago.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.