Two reports caught our attention over the past few days. The first was an article in the Lancet about global fertility rates. The second was a report from the US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) on the Long-term Budget Outlook for the US, looking out over the next thirty years. The two issues are somewhat related.

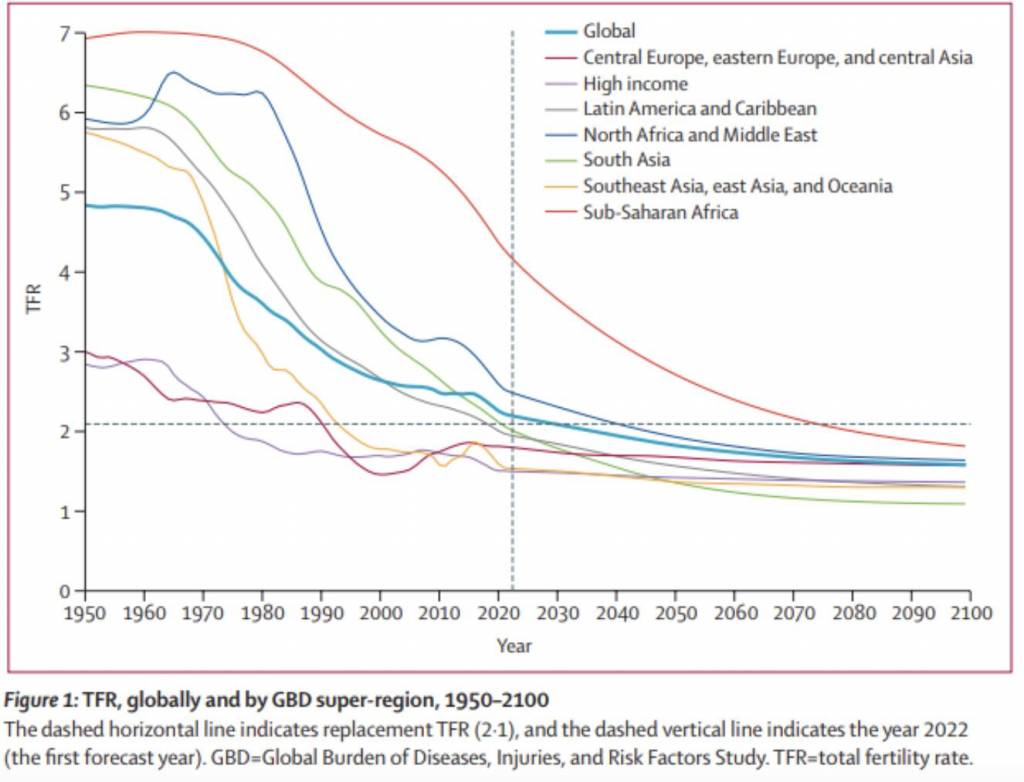

On global fertility, the chart below is really the punchline. It shows fertility rates by region, both historically and projected. The horizontal line at 2.1 represents the replacement Total Fertility Rate – basically the number of children required for the population to remain stable (all else equal). Parts of the world are already below the replacement rate more regions are expected to see their fertility rates drop over the coming years.

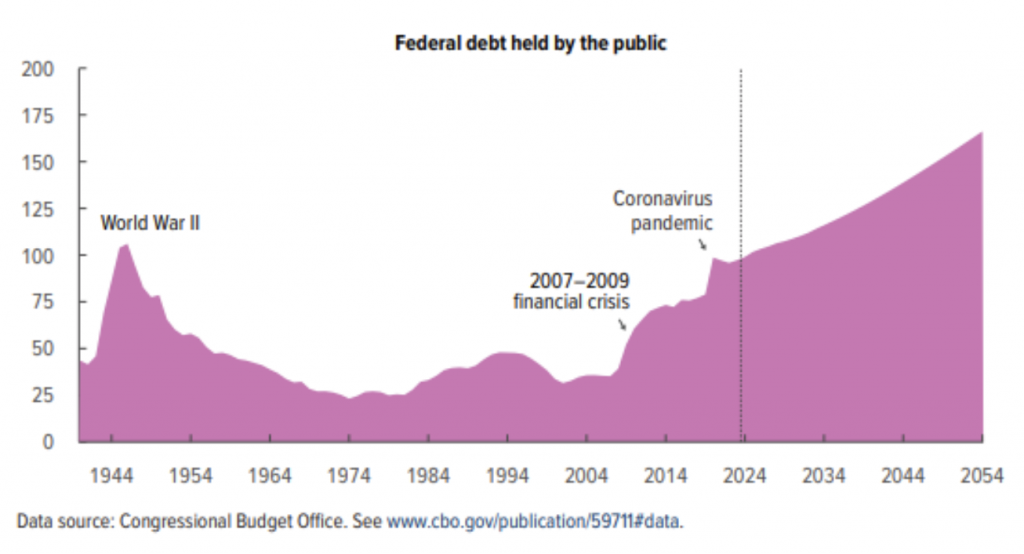

The punchline from the CBO is captured in the chart below. It shows federal government debt as a percentage of GDP over time, including a fairly worrying forecast.

The CBO also makes some assumptions about US demographics, estimating that births would exceed deaths from around 2040, with any population growth coming from net immigration.

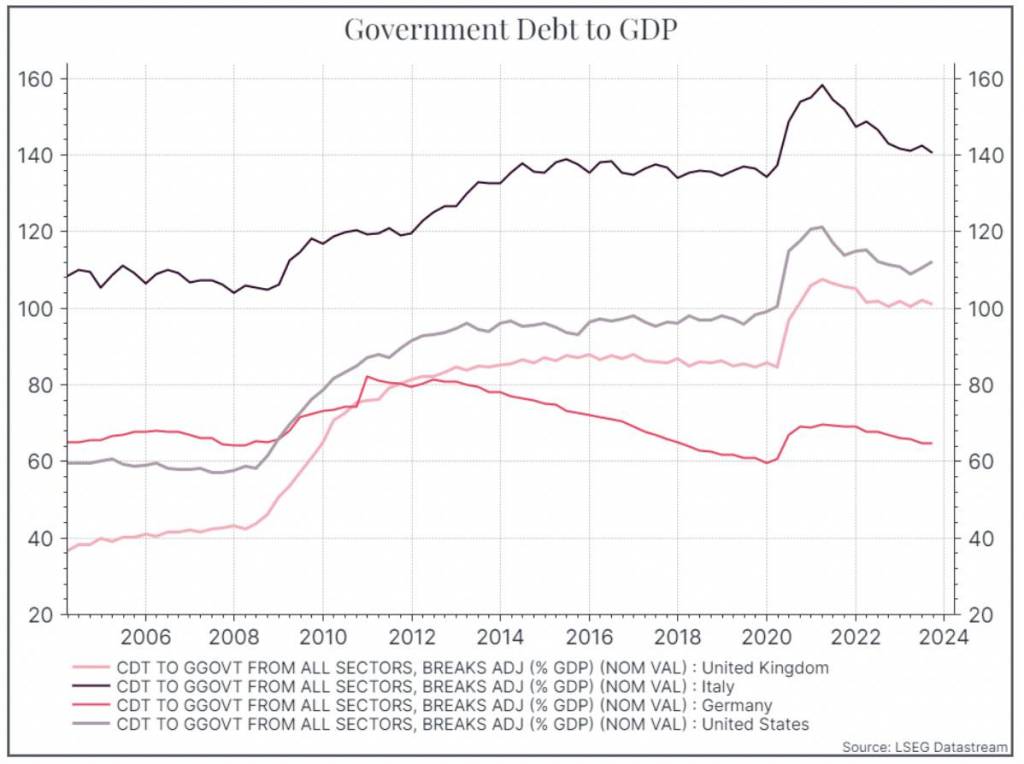

The chart below, looking back at the last twenty years, compares debt to GDP for the US, UK, Germany and Italy. The basic shape for three out of the four is as you’d expect – the Global Financial Crisis and Covid were a significant hit to debt ratios. Only Germany, with a pretty impressive display of fiscal restraint, has managed to buck the trend.

What’s the point of all this? The basic point, at least for today, is that government spending looks set to rise and the number of working-age people available to support it looks set to shrink.

If that’s a fair assertion, then what are some of the potential implications?

First, let’s take a financial markets perspective. Very crudely, it argues that bond yields shouldn’t fall too fair – given the likely growing supply of bonds. Over the past year or so, the focus has been all about central bank policy and the prospect of lower policy rates. That’s important for the short-term outlook, but it’s not the only driver. Supply and demand for bonds also plays a role. From this perspective, the low interest rate regime that we saw post 2009 is likely gone for good.

Second, let’s think about inflation. There’s a lot of discussion about whether an ageing population is inflationary or deflationary. On the one hand, you can go back to supply and demand. Supply of labour goes down (number of workers falls), demand for labour stays the same, so wages should rise. Inevitably, it’s not that simple. What about automation? Won’t we need fewer workers in the future? Maybe. Don’t consumption patterns change as we age? And then there’s the example of Japan – where 10% of the population is now over 80 years old, even as the economy has grappled with deflation for years.

Third, how will governments react? The CBO report is really a cry for action – highlighting the potential trajectory for US government debt. Perhaps the best solution is to find ways to accelerate economic growth. That’s easier said than done even if we shouldn’t dismiss the possibility. Beyond that, you might guess that governments will look to take more and deliver less (however that’s dressed up). It’s not a very palatable outlook. It highlights again, how important it is for individuals and households to save as much as they can for the future in as tax-efficient a way as possible.

Richard Flax: Richard is the Chief Investment Officer at Moneyfarm. He joined the company in 2016. He is responsible for all aspects of portfolio management and portfolio construction. Prior to joining Moneyfarm, Richard worked in London as an equity analyst and portfolio manager at PIMCO and Goldman Sachs Asset Management, and as a fixed-income analyst at Fleming Asset Management. Richard began his career in finance in the mid-1990s in the global economics team at Morgan Stanley in New York. He has a BA from Cambridge University in History, an MA from Johns Hopkins University in International Relations and Economics, and an MBA from Columbia University Graduate School of Business. He is a CFA charterholder.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.