We’ve seen some dramatic moves in bond markets over the past eighteen months or so, and we wanted to take stock of where we are and what we think it may mean for investors and households going forward.

Background

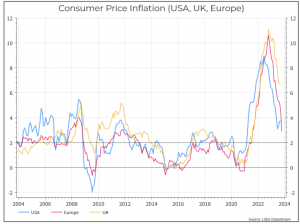

First, a few familiar charts to set the scene. The chart below shows annual inflation for the US, UK and Eurozone. After years of fairly benign inflation, we saw a sharp spike in 2021 and 2022.

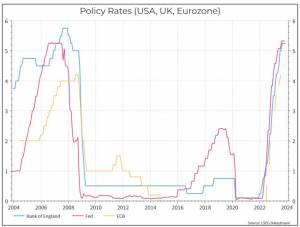

In response, and with belated hindsight, Central Banks raised their policy rates aggressively.

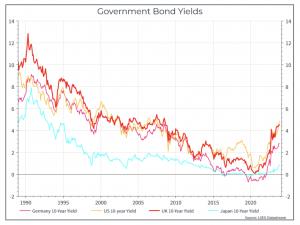

That helped to prompt a sharp rise in government bond yields, breaking a declining trend in yields that had persisted for some forty years.

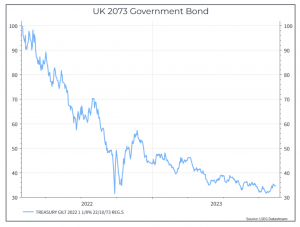

Rising bond yields mean falling prices and that has been painful, particularly for long-duration bonds, whose price is more sensitive to changes in rates. The chart below shows the price of a UK government bond maturing in 2073. Since it was issued in early 2022, it has fallen around 60%.

What does all this mean for households?

Life has become harder if you’re borrowing money.

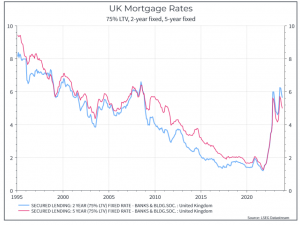

Let’s look at mortgage rates as an example. The chart below shows an aggregate of UK 2-year and 5-year fixed rate mortgage rates. For the two-year rate, we’re back to where we were in the early 2000s.

This situation isn’t unique to the UK. The chart below shows the 30-year mortgage rate in the US – approaching 8% and also back to where it was in the early 2000s.

But if you were a US borrower lucky enough to lock in a 3% rate for thirty years back in 2020 or 2021, then you don’t need to worry about rising mortgage rates until you decide to sell. Many UK mortgage holders will likely see their low rates come to an end in the next year or two, if they haven’t already.

The biggest borrower

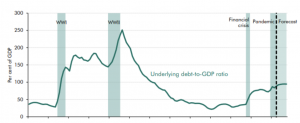

The UK government is the biggest borrower in the country. The chart below from the Office for Budget Responsibility illustrates the point. After decades of decline during the post-World War II period, the debt to GDP ratio has been rising in recent years, driven by the government’s response to the Great Financial Crisis and the pandemic.

That has come at a time of very low interest rates. Higher rates over time should mean that interest costs will rise as well, taking up more of the government’s budget.

It’s also worth remembering that faster GDP growth is a great way to bring down that ratio and improve debt sustainability. But, as we’ve seen, generating faster growth in an economy is no easy feat.

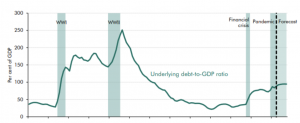

One other nuance relates to interest-linked debt. In theory, inflation is a good way for governments to inflate away their debt. Tax revenues and nominal GDP rise, while the stock of debt that you owe stays the same. It’s not a free lunch, of course. The cost of that is usually borne by households whose wages may not rise as quickly as prices.

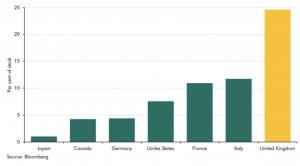

But the UK government has historically issued more inflation-linked debt as a proportion of its total debt than its peers – as the chart below shows. In that case, the coupon that the government pays rises with inflation. The good news here is that as inflation begins to decelerate, the coupon on those inflation-linked bonds will fall from the levels we saw a year ago.

What about savers?

Rising rates have made life challenging for borrowers, and that’s had an impact on the broader economy. But they’ve provided some welcome relief for savers, after years of earning almost nothing on their savings. Banks still aren’t likely to pass on all those rate increases to their customers, but there are other ways to access higher savings rates. Those rates probably won’t help savers to recover the money they lost to inflation over the past decade, but they’re at least providing some contribution.

What about markets and portfolios?

Over the past two years, bond investors have faced two shocks. The first saw a sharp rise in yields in 2022 from very low levels. The second came this year – government bond yields continued to rise, as inflation proved stubborn and Central Bankers erred on the side of caution. That put paid to some of the “Bonds are Back” narrative that we heard at the start of this year.

We’d argue that the pain of the last two years has created a much better environment for bond investors than we have had for some time. Higher starting yields and declining inflation should help support better returns going forward. And, as we consider the long-term outlook for asset classes – the expected returns from fixed-income are higher than they’ve been in years.

Despite that optimistic perspective, we need to consider the potential risks. First, there’s inflation. We think it should drift lower, towards the long-term 2% target, but the global economy is in a fragile place and inflation could still prove stubborn. Second, government deficits are becoming more expensive to finance. The government could try to issue more debt to finance its spending, but that would likely keep yields high. That leaves some tough choices on either revenue (via taxes) or spending (cuts or “efficiencies”). Neither sounds terribly appealing. Starting yields look better, and that’s good news, but the global economy remains a complicated place.

Richard Flax: Richard is the Chief Investment Officer at Moneyfarm. He joined the company in 2016. He is responsible for all aspects of portfolio management and portfolio construction. Prior to joining Moneyfarm, Richard worked in London as an equity analyst and portfolio manager at PIMCO and Goldman Sachs Asset Management, and as a fixed income analyst at Fleming Asset Management. Richard began his career in finance in the mid-1990s in the global economics team at Morgan Stanley in New York. He has a BA from Cambridge University in History, an MA from Johns Hopkins University in International Relations and Economics, and an MBA from Columbia University Graduate School of Business. He is a CFA charterholder.

Richard Flax: Richard is the Chief Investment Officer at Moneyfarm. He joined the company in 2016. He is responsible for all aspects of portfolio management and portfolio construction. Prior to joining Moneyfarm, Richard worked in London as an equity analyst and portfolio manager at PIMCO and Goldman Sachs Asset Management, and as a fixed income analyst at Fleming Asset Management. Richard began his career in finance in the mid-1990s in the global economics team at Morgan Stanley in New York. He has a BA from Cambridge University in History, an MA from Johns Hopkins University in International Relations and Economics, and an MBA from Columbia University Graduate School of Business. He is a CFA charterholder.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.