by Giorgio Broggi, Quantitative Analyst, Moneyfarm

Looking out from its towering height of 632 metres over the Huangpu River as it flows into the imposing estuary of the Yangtze River, the Shanghai Tower is a building of great interest for many reasons. It is a truly extraordinary structure: the second tallest skyscraper in the world. Inside, elevators faster than sports cars transport guests from one floor to another in seconds. The cutting-edge architectural solutions used in its construction earned it the title of the ‘most sustainable skyscraper on the planet’. But despite being a symbol of modern China, the walls of the Tower hide many cracks.

The plans for this mega skyscraper date back to 1993, when the global competition to build the tallest building in the world had not yet begun. Starting from the late 1980s, with the introduction of significant economic reforms that shaped modern China, Shanghai’s urban landscape began to transform and fill up with skyscrapers. In an attempt to establish itself as a financial capital on the global stage, the city embarked on an ambitious project: the construction of a trio of iconic skyscrapers. The Jin Mao Building was completed in 1999, followed nearly a decade later by the Shanghai World Financial Center. But the Shanghai Tower was supposed to be its centrepiece.

Supported by a consortium of state-owned developers and primarily financed by the municipal government of Shanghai, the $2.4 billion construction work on the tower only began in 2008. The twisting tower was finally completed in 2015, attracting global attention for its unusual silhouette. However, since its opening in 2015, the story of the Shanghai Tower has been marred by financial problems, and many more.

By 2019, the building was half-empty, with 55 out of 128 floors completely unoccupied (1) and the luxury hotels that were supposed to populate the tower still remained vacant. This turned the project into a case study. With a collapse in commercial occupancy rates across the city, the new development demanded high rents from tenants at a time when businesses were seeking opportunities. In 2020, a water leak caused significant damage for occupants, raising concerns about construction quality. Even in 2022, 7 years after its inauguration, around 20% of office space remained unoccupied (2).

Despite its universally appreciated design, the Shanghai Tower is not just a monument to Chinese economic success but also its direct opposite. It demonstrates the risks of a vibrant (and indebted) real estate market; a product of years of aggressive urbanisation characterised by excessively high levels of debt and local conflicts of interest.

How did the Evergrande collapse happen?

The situation exploded in mid-August 2023 with the collapse of Evergrande, the construction company known for its staggering debt levels and extravagant management, which had already been in the spotlight at the end of 2021. While the Chinese government managed to fend off the spectre of crisis at that time, the real estate sector remained under market scrutiny. Thus, with an economy facing a slowdown and grappling with structural problems, the Evergrande failure cast a shadow not only over the stability of the Chinese real estate sector but also over the sustainability of Beijing’s entire development plan.

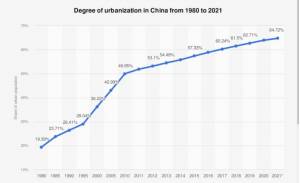

To understand the origins of the crisis shaking the foundations of the new Chinese century, it’s worth taking a step back. Beijing’s economic success has been a unique achievement, built brick by brick. We all know that China transformed in just 30 years from a predominantly agricultural, developing country into one of the world’s major industrial and economic powers. This disruptive growth journey was accompanied by the most unprecedented process of urbanisation in history. Approximately 700 million people, almost 10% of the global population, moved from rural areas to cities to partake in the dream of a new economy.

Figure 1: Urbanisation Level in China from 1980 to 2021. Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, Statista 2022

The new inhabitants of these metropolises needed places to live, and thus the images of mega-skyscrapers, erected overnight from forests of cranes, entered the collective imagination as a symbol of the Chinese miracle. Additionally, both at the central and local levels, the government committed to significant investments in infrastructure to build the backbone of a country with enormous demographic and geographic dimensions. These investments contributed to the development of a range of state-owned, semi-public, and private enterprises that became the protagonists of the Chinese real estate boom.

Financial leverage

To cope with such disruptive demand growth, models were also promoted that allowed the real estate sector to leverage finances that were more than necessary. An example of a widespread scheme is one where buyers advance up to 30% of the property value even before it’s built, without any guarantee that the money spent is tied to the completion of the purchased property. These schemes enabled companies to accumulate a significant amount of debt, effectively spreading some of the risk among buyers.

The role of local governments

Another characteristic of the Chinese real estate development model is the role of local governments. Over the years, the municipalities’ ability to collect taxes and fees has significantly diminished in favour of the central government. Taxation related to land sales and rentals has thus become a fundamental source of income, reaching a peak of 37% of local governments’ fiscal revenues in 2021 (3). Naturally, this created a conflict of interest to approve more projects, sometimes without proper consideration of demand. Local governments also created investment vehicles to directly participate in construction projects (Local Government Financing Vehicles, LGFVs), establishing public-private consortia with builders. These vehicles primarily issue bonds and seek loans, creating additional leverage opportunities beyond central government limits.

An unprecedented pouring of concrete and new rules

In short, we have a system that encourages debt, local conflicts of interest between the public and private sectors, an economic boom, and the largest urbanisation in history. How could it possibly end? With an unprecedented pouring of concrete: it’s estimated that between 2021 and 2022, China produced and used more cement than the entire 20th century usage in the United States (4). The real estate sector directly and indirectly accounted for about 30% of the entire Chinese economy (the real estate sector in the USA on the verge of the 2008 crisis accounted for over 16% (5)). A real estate sector of this size creates a dangerous vicious cycle fuelled by debt. The construction sector requires a growing economy to sustain its debt, while the economy needs an expanding real estate sector to grow.

Like all systems based on financial leverage, however, the Chinese real estate market also faces the issue of appearing as a good idea when things are working until one day they no longer do. Negative economic conditions have overlapped with a natural slowdown in the urbanisation process: the fact that there aren’t another 700 million people destined for Chinese cities is an undeniable reality. The prolonged Covid pandemic lockdown, which lasted longer in China than in the West, further reversed the trend: banks, facing stricter lending rules, reduced mortgage offerings; construction completion slowed down, causing delays and triggering protests and payment boycotts (imagine taking out a mortgage to buy a property that’s delivered years behind schedule). In the background, the government’s attempt to address the issue of debt and financial leverage in the economy with stricter regulations, aiming to undermine the cement (or sand?) on which the Chinese economic miracle had been built.

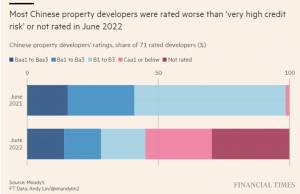

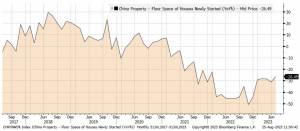

These regulations (including the “three red lines” policy that sets stringent asset limits for property developers) have resolved some critical issues but have also exposed many knots. Evergrande, a $300 billion developer that grew at a peak rate of 44% annually over the last 15 years, became a prominent casualty. But when we look at the health of the 72 largest Chinese developers, we notice a significant deterioration from 2021 (Figure 2), in a market context that has descended from its highs a few years ago (Figure 3), and where, according to the Wall Street Journal, by the end of April 2023, there were even the equivalent of about 4 million completed but unsold homes.

Figure 2: Change in credit ratings of the 72 largest real estate groups in China between 2021 and 2022. Source: Financial Times, Moody’s data.

Figure 3: Annual variation in the area used for new constructions in China. Source: Bloomberg Intelligence.

And what’s happening now?

Now that the bubble is deflating, everyone is wondering about the effects and consequences of the crisis explosion – the real estate crisis has definitely put stress on the market. In recent weeks, we’ve seen many companies, both real estate and financial, facing difficulties. Some estimates measure the potential impact of a 20% contraction in the real estate sector to be between 5% and 10% of GDP, and evidently, this would have consequences not only regionally but also globally.

So, should we be concerned? We can start by saying that problems related to the Chinese real estate sector are not new. The measures taken by the government in recent months (which preceded the recession phase China is experiencing) are aimed at strengthening the builders’ balance sheets, and the government has already intervened with support measures to try to revive the market, both on the demand and credit sides. Beijing has implemented several measures, including:

- Cutting mortgage rates

- Eliminating minimum interest rate thresholds in cities where home prices have fallen

- Establishing a lending window to support completed projects and extend their potential

- Temporarily offering tax incentives for purchasing new homes

- Creating a 200-billion-yuan rescue fund for developers, in addition to around 600 billion yuan in local financing

- Encouraging banks to maintain available credit, even if this makes them non-compliant with regulations

As a result, statistics on new constructions have stopped plummeting, but for now, none of these initiatives seems to have restored public confidence in developers’ ability to carry out projects. The decline in demand is also causing issues for other developers, such as Shimao and Country Garden, which, though having stronger balance sheets than Evergrande, have both missed debt payments. Overall, according to The Guardian, companies responsible for 40% of property sales in China have struggled to meet their debt obligations since the introduction of the “three red lines” regulation. Bloomberg states that the amount of debt from property groups at risk of default is equivalent to 12% of GDP.

The question everyone is asking is how long the government will stand by and when will it decide to intervene with direct measures that support the struggling companies’ balances or the creditors. Beijing’s doctrine in recent years has been to manage the transition to an economy less dependent on real estate, even accepting that some developers fail.

However, this approach could change if the crisis were to take on more systemic characteristics. Predicting with certainty how the Chinese government will act is not simple, and this to some extent creates concern in the markets. Chinese policymakers might prefer focusing on structural improvements in the real estate market rather than simply allocating more money to solve the problem. The Chinese Communist Party is concerned about China’s medium and long-term interests, but logic suggests that if the crisis were to expand, measures aimed at short-term containment might be taken to protect these interests.

Looking back, we are reassured by the fact that Chinese policymakers have had a fairly good track record in managing economic challenges. We remember significant stimulus packages, particularly after the Great Financial Crisis, often focused on investments and the real estate sector. The fundamental thesis is simply that, even though the yuan is currently under pressure, the Beijing government has the ability to tap into massive resources (including incorporating part of the debt) if the crisis continues to spread, especially if it were to hit the official banking system.

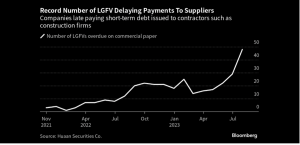

Concerning the risk of possible contagion in the banking and financial sector, its exposure to the real estate market doesn’t seem unmanageable for the moment, although there’s always the risk that Beijing might be underestimating the depth of the crisis, partly due to the fragmented financial architecture that emerged in the shadow of the Chinese economic boom. The greatest risks are hidden in the not-always-transparent balance sheets of LGFVs (Local Government Financing Vehicles) and, above all, in the immense shadow banking system, a constellation of financial institutions whose exposure to the real estate market remains difficult to quantify. The news that some large wealth managers, like Zhongrong Trust, have missed payments on some of their products is definitely significant, and the effects of the crisis on the financial system need to be closely monitored. For the moment, although the number of struggling LGFVs is significantly increasing, the situation is manageable, as less than 50 out of around 3,000 are having issues (Figure 4). Certainly, it becomes essential, especially in the medium term, for Beijing to increase monitoring and control activities over these entities. The Lehman Brothers episode teaches us that risks are much higher when transparency is low, and the incentive system rewards risk-taking and audacity.

Figure 4: Number of LGFVs that have missed payments on commercial papers, source Bloomberg.

Conclusions

The Chinese real estate crisis doesn’t come as a surprise. It unequivocally exposes some limitations of the country’s economy: demographic issues, limited diversification, an overly developed real estate sector, and governance, especially at the local level, that doesn’t always work optimally. The crisis is partly the result of the government’s attempt to address these medium-term structural problems, paying the social, political, and economic costs today.

Chinese financial assets have also paid the price, historically struggling to reap the benefits of the country’s economic growth. These limitations are among the reasons why at Moneyfarm we have chosen to underexpose China in our allocations (up to around 5% in the riskier lines).

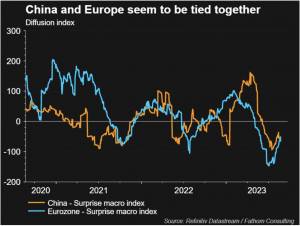

While the Chinese crisis has a very limited direct impact on our portfolios, it could have an effect on global growth and risky asset prices, especially in Europe. The latest European macro data suggest a slowdown and are surprising on the downside, certainly not helped by the economic situation of the Asian powerhouse (Figure 5). Even the Shanghai shipping rate indices have plummeted, although they still remain in line with pre-Covid levels.

Figure 5: Macroeconomic Surprise Indices for Europe and China, published by Citigroup.

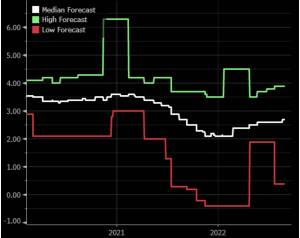

Overall, for the time being, the global economy seems resilient enough to endure, as evidenced by the ongoing upward revision of average global growth expectations collected by Bloomberg (Figure 6). However, the Chinese situation adds significant risks, and this remains one of the reasons why we continue to be marginally underexposed to risky assets in our portfolios.

Figure 6: Global GDP growth expectations for 2023 collected by Bloomberg.

However, we believe that the Dragon has the resources, at the very least, to avoid a severe crisis in the short term, even though, in pursuit of longer-term objectives, it seems prepared to bear an economic and political cost that could indeed weigh on assets and growth expectations, both for China and to some extent globally. For now, amidst partially vacant skyscrapers and unfinished ghost cities, the real estate giants are collapsing loudly, while the global economy watches, fearful but sturdy.

Giorgio Broggi: Giorgio joined Moneyfarm as a Quantitative Analyst in December 2021 and he is a member of the Investment Committee. Prior to joining the company, he worked at Barclays Wealth Management and S&P Market Intelligence, gaining expertise in Funds Research and ESG Investing. Before starting his professional life, he successfully completed a double-degree at Eada and EDHEC Business School, obtaining two Masters in Finance and specialising in factor investing and portfolio construction. He is a CFA charterholder.

Giorgio Broggi: Giorgio joined Moneyfarm as a Quantitative Analyst in December 2021 and he is a member of the Investment Committee. Prior to joining the company, he worked at Barclays Wealth Management and S&P Market Intelligence, gaining expertise in Funds Research and ESG Investing. Before starting his professional life, he successfully completed a double-degree at Eada and EDHEC Business School, obtaining two Masters in Finance and specialising in factor investing and portfolio construction. He is a CFA charterholder.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.