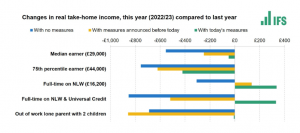

What are we talking about? The UK government has announced a package of measures to support households hit hardest by the sharp rise in the cost of living. The package is funded, at least in part, by a “windfall” tax on profits in the energy sector. The headline numbers are, according to the Treasury, around £15 billion of additional support, targeted at lower-income households. The immediate reaction was fairly positive – partly because the package is . According to the independent Institute for Fiscal Studies, it means that the median income earner will see their take-home pay stay roughly flat in real terms compared to last year. Lower income workers will see a higher real take-home income, relative to last year. Higher earners will see some benefit, but far less, as the chart below illustrates. The message from the government seems to be that these are one-off measures, but there could be more – presumably depending on how the economy develops.

The collective instinct of Conservative Chancellors has been to try to balance the books early, but the pressure on households has become too great, particularly given the prospect of another significant increase in the utility cap in October. Fiscally, the impact should be contained – first, because in theory this is a one-off, second, because some of it will get funded by the windfall tax and, third, maybe more controversially, because if you’re able to issue debt at 2% nominal (roughly where the UK 10-year yield is) and you’re inflating that debt away at 10%, then you’re probably ok – at least for now. That last point does depend on inflation coming down fairly soon, so it wasn’t especially reassuring to hear the governor of the Bank of England, in his latest testimony, claim that there wasn’t much he could do about inflation and that we should brace for a recession – or something close to it (he didn’t quite say it like that, but that was the message). And you might imagine that the stagflationary forecasts that are presumably flying around had some impact on the Chancellors thinking.

The windfall tax on profits is interesting to us. It’s the result of “excessive” profits caused by higher natural resource prices. The energy companies might reasonably say that no one came to help them when the oil price was at $30 per barrel (or zero!). The CBI (Confederation of British Industry) came out to say that a windfall tax would discourage investment, which theoretically makes sense – after all, if you didn’t think you could earn a return, you wouldn’t invest. From an ESG perspective, you might think that was a desirable outcome in the long-term, but we also know that energy demand isn’t going away and that capex in the industry generally has lagged. That’s a recipe for higher prices. Anyway, it’s all a bit academic because the Chancellor has made capital spending deductible from the profit calculation (up to a certain percentage) as an incentive to the industry. That presumably means the government will cover more of the total bill than it would otherwise have done.

Where does this get us? The government has increased its support for households in the wake of a very significant increase in the cost of living. It seems like the right thing to do, given the challenges facing households, particularly from rising food and utility bills. On the margin, it’s probably supportive for growth – and the outlook for UK growth looks pretty weak at the moment – and for sterling, which has weakened against the dollar in recent weeks. But this isn’t a return to the generosity of 2020 and Mr Sunak will be hoping, like the rest of us, that inflation will begin to slow without too much damage done to the economic outlook. It remains a difficult environment.

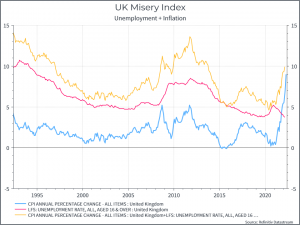

One final aside, in the course of writing this, we looked at the Misery Index, a cheery economic indicator created by an American Economist. It basically sums up inflation and the unemployment rate, as a fairly blunt indicator of the overall health of the consumer. The chart below tracks the index over the past thirty years.

Interestingly, despite the very sharp rise in inflation, the Index is still below where it was in 2011 and 2012 – when unemployment was much higher and inflation was lower. You could argue that it reflects the relative health of the labour market – with jobs still fairly plentiful. A more negative view would say, first, that unemployment is a lagging indicator, which is why the recent peak of the Misery Index was some two years after the Financial Crisis. Second, you might reasonably argue that having low unemployment with negative real wage growth isn’t particularly supportive – hence the Chancellors intervention today.