Lately, there’s a term that has come back into fashion among economists, analysts, and financial market operators: stagflation. The term “stagflation” refers to a period in which the economy experiences high inflation and low levels of real growth. The reason why this word has returned to the lips of many recently is related to the phase of the economic cycle that the European Union and the United Kingdom are going through and the scenario they could be projected into in the near future.

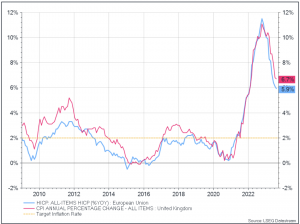

As is known, in recent months, inflation has forcefully reappeared in our lives. The shocks suffered by supply chains, production, and distribution due to the Covid-19 pandemic and later the Russia-Ukraine invasion have led the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to levels well above the historical range of the recent period and far from the 2% target of Central Banks (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Time series of year-on-year Consumer Price Index (CPI) for the European Union (blue line) and the United Kingdom (pink line).

The response from the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England (BoE) to the inflationary shock was swift, leading to the most rapid interest rate hike in recent history. The high level reached by interest rates has contributed in recent months to cooling the inflation trend. However, despite the efforts made by central bankers, inflation continues to remain at very high levels and well above the ideal value of 2%.

The inflation currently experienced in the European continent is fundamentally the result of two contributing factors:

- Monetary inflation: This is inflation resulting from the high monetary stimulus injected into the economy by central banks to cope with the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Supply-induced inflation: This is inflation primarily resulting from high production costs, which consequently impact end consumers, increased due to the energy shock following the Russia-Ukraine invasion.

Although both inflationary dynamics contribute to an overall increase in inflation, supply-induced inflation is much more difficult for central bankers to control and runs the risk of having negative effects on growth as well. To complicate the growth perspective further, there are measures implemented by central banks in this context. A high level of interest rates essentially means a high cost of money, which complicates access to credit for businesses and individuals, leading to an economic contraction.

Despite the events of recent months being clear, what is the current situation in the UK and the EU in terms of growth and inflation?

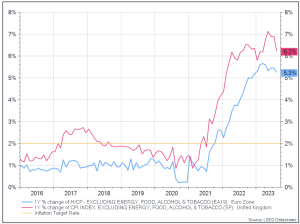

The tightening of monetary policy has certainly helped deflate, at least partially, the inflationary trend, as explained earlier. However, inflation is composed of various components that can react differently to interest rate levels. The metric that central banks tend to focus on more for a measure of inflation that is as close as possible to reality is the so-called core inflation. Core inflation is measured based on the increase in prices of the same basket used to calculate the main CPIs (Headline CPI – Figure 1), but excluding goods related to food and energy. The removal of these two components, whose prices are historically very volatile, contributes to making Core CPI a more reliable metric for estimating the “real” level of inflation.

As shown in Figure 2, Core inflation has only recently started to exhibit timid signs of slowing down, characterised by a much slower pace compared to Headline CPI. Price stability and the 2% inflation target are still far from being achieved. However, in the latest meeting, the ECB has given more or less cautious signals of having reached the peak of its monetary tightening cycle, stating that, if sustained long enough, the current level of interest rates will be sufficient to bring inflation in the EU under control.

Figure 2 – Time series of year-on-year Core Consumer Price Index (CPI) for the European Union (blue line) and the United Kingdom (pink line).

Regarding the United Kingdom, in the September 2023 meeting, the BoE decided to opt for a pause and not raise its benchmark rates further. However, the situation in the UK seems to be slightly less under control than in the EU (the difference between the two respective Core inflation rates is 0.9%), and therefore, at least one more prospective rate hike is considered likely by market operators.

From an inflationary perspective, the situation seems to be more under control than a few months ago, but the game is far from being won. Moreover, the significant increase in the price of oil barrels in recent weeks, and the fact that the winter season is approaching, brings the impact of energy costs back into the debate, which, in the case of a cold winter and high consumption, could play a significant role in preventing the slowdown of inflation in both the UK and the EU.

And what about growth?

As mentioned earlier, the current economic context and the various stresses on supply chains have contributed to downward revisions in growth estimates for the UK and the EU. For the EU, the Summer 2023 Economic Forecast predicts an annual nominal GDP growth rate for the Euro Area of 0.8% in 2023 and 1.3% in 2024. Both estimates have been revised downward compared to the previous Economic Forecast. Regarding inflation, expectations remain high. In 2024, it is estimated that the Euro Area headline inflation will be around 5.6% by the end of 2023, then significantly normalising in 2024, reaching the level of 2.9%.

In the United Kingdom, the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) estimates GDP growth at 0.3% in 2023 compared to the previous year and 0.8% in 2024. Regarding inflation, the BoE expects to end the current year around the 5% level and gradually reach the 2% target only in 2025.

Stagflation, why?

As we have seen, the macroeconomic picture depicts persistently high inflation and positive but slowing growth compared to previous estimates. However, there are some clouds beginning to gather on the horizon, increasing the pessimism of some economists, especially concerning growth expectations.

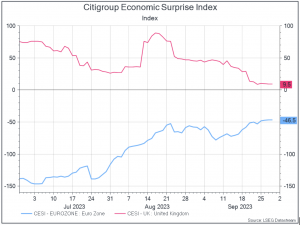

In particular, as shown in Figure 3, the sentiment regarding surprises related to the publication of economic data remains strongly negative for the Euro Area and is sharply declining for the United Kingdom. This indicator, widely popular among market operators, estimates how regularly published economic data surprises the values expected by analysts. If the indicator is positive, it means that, on average, economic data has pleasantly surprised expectations, and vice versa if the indicator is negative. Therefore, the Euro Zone, by consistently falling below expectations, continues to show signs of weakness, and the United Kingdom shows signs of deterioration.

![]()

Figure 3 – Performance in the last 3 months of the Economic Sentiment Indicator (CESI) for the Euro Area (blue line) and the United Kingdom (pink line).

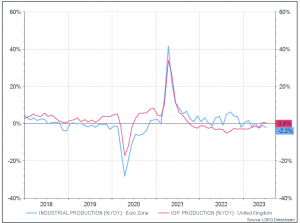

Another crucial metric concerns industrial production (Figure 4). The year-on-year growth rates are currently at -2.2% for the EU and 0.4% for the UK, confirming that the stresses experienced have not yet been fully absorbed.

Figure 4 – Historical series of Industrial Production for the Euro Area (blue line) and the United Kingdom (pink line).

These data partly explain why the word “stagflation” has come back into fashion for many. Inflation remains well above the cautionary levels, and the increasing uncertainty in the energy sector poses additional challenges that could slow down its normalisation. Regarding growth, both the EU and the UK have revised their estimates downward, and the production environment still presents several challenges that could further undermine the overall picture, resulting in the coexistence of high inflation and low or negative growth within the same scenario—hence, stagflation.

It is crucial to highlight that, although the EU and the UK are facing a context with many similarities, the differences between the two cases are significant (considering that the Euro Area is composed of 20 different economies), and the specificities involved could lead the two cases to develop differently.

On our part, we constantly monitor the evolution of the macroeconomic and geopolitical context to optimize the risk/return profile of our portfolios. Currently, the Asset Allocation team does not consider stagflation the most probable scenario. Our baseline scenario predicts that the economic slowdown will be contained and will, in turn, be “accompanied” by a gradual normalisation of inflation. Therefore, we believe that a conservative and well-diversified positioning can bring benefits to investors given the uncertainties currently present in the market.

Davide Petrella: Davide is a Portfolio Manager at Moneyfarm. He earned an MSc in Quantitative Finance from Politecnico of Milan Graduate School of Management and a MSc in Physics at University of Rome La Sapienza. Davide started his career in Anima Sgr in 2017 as Assistant Portfolio Manager in the multi-asset team and then he moved to Allianz Italy in the ALM & Strategic Asset Allocation team. From January 2022 to January 2023 he worked as Quantitative Analyst in the Fixed Income Boutique of Vontobel Asset Management in Zurich, working closely with Portfolio Managers in order to build quantitative front-office solutions for the boutique.

Davide Petrella: Davide is a Portfolio Manager at Moneyfarm. He earned an MSc in Quantitative Finance from Politecnico of Milan Graduate School of Management and a MSc in Physics at University of Rome La Sapienza. Davide started his career in Anima Sgr in 2017 as Assistant Portfolio Manager in the multi-asset team and then he moved to Allianz Italy in the ALM & Strategic Asset Allocation team. From January 2022 to January 2023 he worked as Quantitative Analyst in the Fixed Income Boutique of Vontobel Asset Management in Zurich, working closely with Portfolio Managers in order to build quantitative front-office solutions for the boutique.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.