Imagine you bought a Ferrari, but you discovered that under the bonnet there was a Fiat engine. In the asset management industry, this is called Index Hugging.

This February the European Security and Markets Authority (ESMA), the Authority that contributes to safeguarding the stability of the European Union’s financial system, provided the preliminary details of its latest study focused on verifying and quantifying the practise of Closet Indexing in the European asset management industry.

Closet Indexing (also known as index hugging) refers to the practice of fund managers claiming to run an active portfolio while in reality they are just replicating a benchmark, whilst charging management fees in line with actively managed funds. This strategy requires less effort form the portfolio manager so in theory fees should be lower. In reality it results in a practice that leaves investors worse-off than if they had bought a cheaper index in the first place.

The case

The investigation carried out by ESMA was prompted after several shareholder’s rights groups complained that funds were charging high fees for active management, whilst mimicking an index. The first complaints came from Better Finance, the Brussels based investor protection group, which in 2014 called on ESMA to investigate. Since then, some regional regulators started to put effort into finding and pursuing index huggers.

The Norwegian market authority was the first in Europe to make a public accusation. In March 2015 they accused the largest Norwegian bank (DNB) of mis-selling a “closet tracking” fund. During a wider investigation into whether Norwegian equity funds are actively priced and marketed, the regulator examined the indicted fund over a five-year period and found that the fund performed very closely to the benchmark, but was marketed and priced as an actively managed fund.

In December 2014, the Swedish Shareholders’ Association accused Swedbank Robur, the asset management arm of Sweden’s largest bank, of mis-selling funds that charge high fees for active management but do little more than mimic an index. The claim was filed with Sweden’s National Board for Consumer Disputes, and there was a strong denial from the Bank. Later on, the claims were extended to two more of the biggest banks in Sweden, Nordea (also admonished by Norwegian regulator) and Handelsbanken. The case was dismissed in July by Sweden’s National Board for Consumer Disputes, there were suspicions of lobbying activity by the bank. Nevertheless, it helped to put a spotlight on this practise which is spreading across Europe. Following these cases, the Danish authority also started to investigate the matter.

Recent development

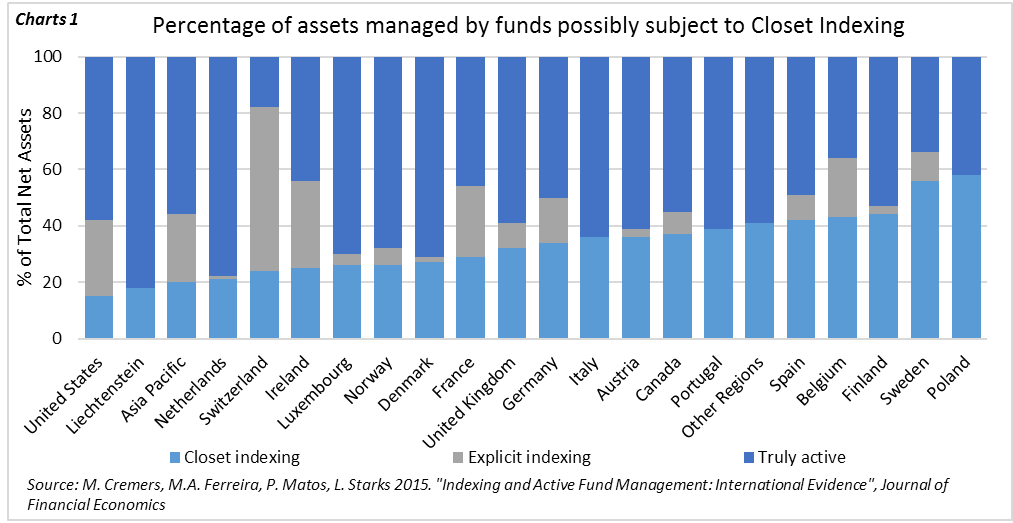

Recently, some academics started to show interest in closet indexing practises. Last year a pool of professors from universities across the globe wrote “Indexing and Active Fund Management: International Evidence”, in which they tried to quantify the amount of total net assets in developed markets that are actually passively managed but actively charged. They define an index manager as a closet indexer if the fund holds an active share (share of portfolio holdings that differs from the benchmark index holdings) lower than 60%. Chart 1 illustrates the results of their study.

In this study, academics found that in some countries, especially in Europe, more than half of domestic equity funds could be closet indexers. Whilst the US, the world’s largest asset management market, had the lowest proportion of closet trackers. It is easy to see a strong relationship between the percentage of index huggers and markets dominated by large banks with strong distribution capacity.

Results of ESMA investigation

ESMA selected a sample of funds publicly sold in Europe, with assets under management bigger than €50 million, management fees higher than 0.65% and an inception date before 2005. The resulting sample contained more than 2,600 funds, of which, only 1,251 had enough data to be analysed. It used active share tracking error (volatility difference in returns between the fund and its benchmark) and other statistical metrics to define index huggers. The preliminary results show that between 5% and 15% of actively managed equity funds in Europe could be closet trackers, underlying the necessity of additional supervisory work.

What is next

At the moment, despite a lot of pressure from different associations, ESMA refuses to publish the names of the suspected index huggers. It is now up to the national regulators to set a framework for further investigation, and we can be sure that it is only the beginning of a process that will help to make the asset management industry cheaper and more transparent.