In our second edition of Moneyfarm Green, we’d like to update you on the latest trends in sustainability – including in-depth analysis and how to identify the latest opportunities – what we can expect from the global water crisis and an update on our ESG portfolio performance.

Last year was challenging for ESG portfolios due to the energy crisis, Ukraine conflict and hawkish monetary policy. This year performance is proving to be more stable and year-to-date we are also seeing an over-performance in the ESG sector.

The main drivers are the opposite of last year. Firstly, growth tilted companies are over-performing, thanks to earnings season and to monetary policy that should have peaked, with long-term interest rates decreasing. Secondly, fossil fuel-related companies are not over-performing like last year, thanks to a reduction in energy prices, such as oil, down by 15% YTD. On the other hand, the factor tilt to smaller companies has been a negative contributor on returns, but that was not enough to offset the gains.

Short-term over-performance in a long-term investment strategy should matter up to a point. ESG performance YTD shows how periods of tension, like last year when oil companies outperformed the S&P 500 by 100%, if not supported by long term fundamentals, might normalise over time. We construct ESG portfolios with the aim of having a similar risk-return profile in the long-term to a classic investment portfolio.

Is sustainable investing still… sustainable?

You’d be forgiven for thinking that prevailing market conditions have dampened enthusiasm for ESG investment. But looks can often be deceiving and the longer-term outlook may be much brighter than current conditions suggest.

Although we must bear in mind the sector’s new challenges ahead for the year, including:

- Larger investment firms’ waning interest in the ESG sector since the turn of 2023;

- A rising anti-ESG movement stateside which is rapidly gaining momentum.

As we outlined in our Strategic Asset Allocation 2023, we believe sustainability is not a passing, short-term trend, but one which will become essential in the long-term as we face an impending climate crisis.

The ESG investment landscape, especially in the Eurozone, is undergoing some important regulatory, political and monetary changes.

Perhaps the best example of this would be the interim EU-wide agreement on European green bonds, which seeks to set out a transparent framework for green bond valuation. This development is especially timely as the ongoing fight between the regulator and ‘greenwashing’ firms comes to a head.

On one hand, there are arguments that the current legal framework should make it increasingly difficult for companies to greenwash; however, on the other, many now argue that it could promote the practice of ‘green-bleaching’ (that is the underselling of sustainable products so as not to incur any regulatory penalties) which could, in turn disincentivise investment in the future of ESG.

The truth probably lies somewhere in between: While it’s vital to fight the mis-selling of financial products at all costs, we must also prevent legislative complexity from discouraging the evolution of the ESG sector in the Eurozone.

As regards monetary policy, however, a new report from the ECB makes for interesting reading. In it they publish for the first time the trend of average greenhouse gas emissions of bonds held by the Bank. Since October 2022, the institute has pledged to overweight corporate bond purchases of issuers with “better climate performers”. The importance of monetary policy cannot be underestimated, not only for the real-word economy but also for financial assets more generally.

Monetary policy decisions going forward, therefore, could have huge positive impacts for the future of the ESG sector – a central plank of our Moneyfarm SRI portfolio range objectives.

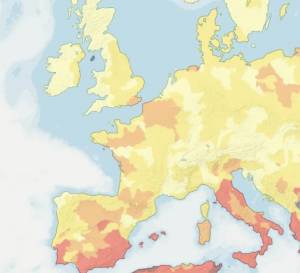

Our chart of the month: Water availability fast disappearing

Our latest graph gives a striking snapshot of growing global water shortages. Areas in yellow represent low-risk regions, orange medium and red those at the highest current risk of drought.

Currently, an estimated 40% of the world’s population are suffering the effects of water shortages, with the situation becoming progressively worse in many areas, as the chart shows. There is an increasing probability that one day, in the not too distant future, all the taps in the world could run dry. This phenomenon is known as ‘Day Zero’.

According to the World Resources Institute (WRI), there are 17 cities that are experiencing the greatest shortages of water. But this figure could rise to 45 – affecting a further 455m people – in the very near term should solutions not be found.

A growing shortage of water is one of the most underestimated crises that the world faces at this moment in time. The potential impacts on agriculture, global migration, the financial system and even the possibility of regional conflict cannot be underestimated.

Turning our attention to mainland Europe and the water shortage’s impacts there, by looking at the map below, we can see that Italy is at a much higher risk of water shortages than many major European economies, such as France and Germany. Even during the summer months of 2022, water rationing measures were introduced, and concerns about droughts in the coming months are already mounting. In fact, some regions have already set out plans to limit water consumption to only ‘essential’ activities between the start of June and the end of September 2023.

Moneyfarm portfolios in focus: our levels of ESG investment

When we talk about ESG investment, we’re talking about a wide-range of products, such as: socially responsible investment packages that exclude companies with negative impacts on society, investments that take financial risk into consideration as a sustainability factor, and others which generally have positive impacts on society and the environment.

The European-wide Sustainable Financial Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), in particular, helps us to better clarify the final category listed above. The regulation states:

“Sustainable investment is defined as an investment in an economic activity that:

- contributes to an environmental or social objective;

- the investment must not cause significant damage to any environmental or social objective (DNSH);

- the company benefiting from the investments must follow good governance practices.”

What we must ask ourselves is: how do we know if an investment “contributes to an environmental or social objective?”

One of the most common approaches is to analyse each company from two different perspectives:

What is generated: We consider whether a company’s revenues (and at what percentages) derive from products or services with a positive impact on society or the environment. Among the economic activities we consider sustainable are: mitigation of climate change and its impacts, the prevention of pollution, and responsible management of water, forestries and other natural resources.

If we look at what is generated from a social standpoint, however, we are likely to consider: access to healthcare provision and social care, housing, food and financing for SMEs.

How is it generated: Here we take into account the entire production process of the product or service offered and impacts or potential impacts on stakeholders. We measure all of these factors in relation to the international framework provided by the United Nations Global Compact and OECD. Good governance is also a central theme of our overall company analysis.

As the regulator reminds us: it’s not enough for us to buy electric cars if the trade-off is using exploitative child labour in developing countries to mine cobalt and other materials necessary for production.

In terms of thematic bonds (green, social or sustainability), it could be theoretically possible for all the investments to be sustainable as both private and public is needed for environmental projects in the longer term. However, an analysis of the Do No Significant Harm (DNSH) principle alongside good governance could decrease this percentage chance of long-term sustainability.

However, we must also consider that investments which are aimed exclusively at sustainable solutions can lead to an increase in the risk of concentration and consequently the volatility of the investment. The objective of Moneyfarm’s SRI portfolios, therefore, remains to invest in global markets with a ‘risk-return’ profile similar to a traditional multi-asset investment.

The following table shows the share of sustainable investments in our SRI portfolios relative to our classic portfolios. The results are calculated by processing MSCI data and information provided by ETF issuers.

The increases between each portfolio’s relative performance in the table are considerable and can be enhanced by investing in our sustainable thematic portfolio, according to your own risk tolerance.

We will continue to explore the best techniques to increase exposure, but without decreasing the portfolio’s risk too much.

*As with all investing, financial instruments involve inherent risks, including loss of capital, market fluctuations and liquidity risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is important to consider your risk tolerance and investment objectives before proceeding.