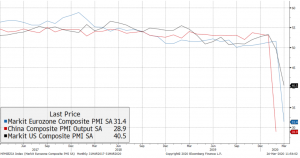

If further confirmation of economic crisis was needed, it came from European PMI data. This month, it fell to its lowest levels for over 20 years – that is, since records began. The IHS Markit Eurozone Composite PMI Flash stood at 31.4 in March, collapsing from 51.6 and recording the largest monthly drop in the survey’s history. In the United States, requests for unemployment benefits, a proxy for labour market trends, have exceeded 3 million. This is a record figure, which helps to put the effects of the current global crisis in perspective.

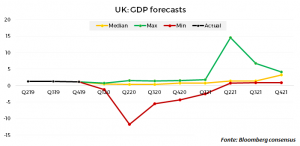

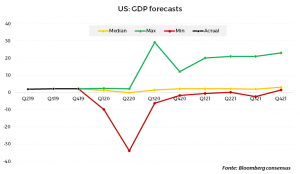

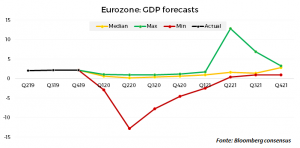

There seems to be little doubt: we are heading towards a recession. What analysts are now exploring is just how significant this recession might be. Forecasts vary wildly, which reflects the uncertainty of the moment and the difficulty in finding quality data as the situation changes quickly.

The grimmest estimates predict a shrink of -30%, unprecedented contractions even after 2008. On the other hand, this is not surprising, with the global economy virtually frozen and over a third of the world’s population in quarantine.

The good news is that, despite the bad omens, the markets are reacting. Last week saw some of the most positive performances in recent months.

This is not to suggest that the crisis is coming to an end. Rather, this uptick can be taken in two ways:

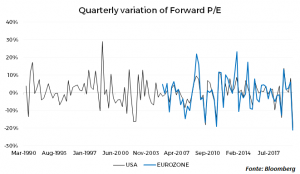

- Markets had already factored the possibility of a recession into their prices. If we look at the quarterly change in the expected price/earnings ratio, we see that the current depreciation has been unrivalled in its speed. Historically, changes like these tend to come with recessive economies. The markets were quick to price in a recession, which even the most responsive data struggled to keep up with. This tells us a lot about the current reactivity in the markets.

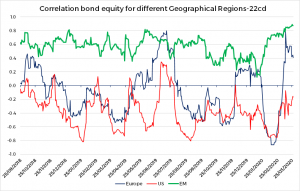

- In the last month, the behaviour of the markets has been unique. Speculative and defensive repositionings have taken place as a reaction to the volatility itself. For example, the past two weeks have seen a marked increase in the correlation between equities and bonds. This is probably a self-sustaining dynamic, stemming from leveraged investors liquidating their positions. We believe the impact of this will be short-lived – correlations have been normalising in the last few days – but this is another symptom of the peculiar circumstances in which we find ourselves. The good news is that markets have begun functioning more predictably over the last week.

There is limited comfort to be found in the data at present, but it does seem to support the prevailing thesis: that the second quarter will be defined by a deep recession, which will then be largely recovered in the second half of the year when economic activity resumes. This is a view that we, at Moneyfarm, share.

The current circumstances are wholly exceptional. To understand the economic impact, then, we must forget the standard assessment of a recession. Ordinarily, when a recession occurs, the crisis is transmitted from consumption and investment to corporate profitability, and then onto the labour market and wages, until the cycle reverses. Politicians – in this case – can intervene with anti-cyclical and expansionary policies to try and reverse the recessionary cycle.

A large portion of the global economy has effectively been frozen, with the health emergency only under control in a handful of countries. This means that, as long as this crisis lasts, injecting liquidity into the economy will not reverse the trend. If people are confined to their homes and cannot spend, even transferring money directly to their bank accounts will not – in the short term at least – serve to increase consumption.

Just like a company, it doesn’t help to offer credit and liquidity without also offering support and guarantees to business and consumers (like we have seen in the UK and Germany) to boost investments and hiring.

Another factor is that not all sectors will be impacted equally. The transport industry, for example, will be significantly hit as entire countries are put into lockdown. This is an industry that will remain in a state of crisis for far longer than other, less affected areas of the economy.

The digital economy can, largely, continue to operate without any issues. Not only that, but it also benefits from a situation in which billions of people are told to stay at home and work remotely.

Markets have been unable to effectively evaluate prices thanks to the wider uncertainty around the situation. As that uncertainty thins out, though, we seem to be moving towards a more granular price revaluation. This is good news, suggesting a gradual return to something resembling normal service. The VIX, for example, has returned to relative stability as intra-day changes are decreasing.

There is no historical precedent for this situation – the most similar we have seen were periods of war. The political response must cover four key areas:

- Firstly, they must intervene to ensure that supply chains do not collapse during the lockdown. Countries have moved at different speeds and have unequal resources available to survive a situation in which the economy is frozen. In the short term, the aim is to keep the system liquid and mitigate the damage caused by the quarantine.

- Secondly, they will need to support growth. We have already some of the world’s richest countries act, but international coordination is lacking. This is particularly stark in Europe, where you would expect greater cooperation. We do, however, expect Europe to find a united response to the crisis, given the magnitude of the question it poses.

- The third key area is that of managing the marked inequality of impact between sectors. For obvious reasons, we consider this the main source of downside risk today. It is still difficult to assess the extent of the imbalances, as well as exactly how different geographies and supply chains will be impacted.

- Finally, this will all need to be followed by liquidity management, control of possible inflationary pressures and restructuring of public debt, in what could be considered a new global financial balance to be built in the next decade.

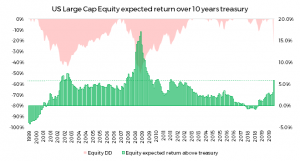

To end on a positive note, medium-term valuations and equity risk premiums are in a very healthy state for investors. This represents a golden opportunity to enter the market at or near the bottom of a dip, an opportunity that should be seized by investors in the immediate future.

The true economic recovery will come when the global health crisis is under control. Here, though, we must agree on exactly what we mean. Governments must decide not only how to contain and defeat the disease, but how systems and safeguards can be put in place to guarantee economic recovery once the crisis is resolved. In this sense, the progress that has been made in a matter of weeks, regarding the reorganisation of health systems and the use of technologies for testing, is encouraging.

The fact that the scientific community is currently lacking cohesion on various issues does not help in setting a realistic horizon. We are learning more about the virus every day, and though it is certainly too early to say that we can see the light, the mists of uncertainty are beginning to unravel.