We are not even a month on from the UK’s official withdrawal from the European Union and ‘phase two’ is already well underway. Earlier this month, the EU and the UK made their opening bids, as they started negotiating their future economic relationship. Indeed, this is yet to be defined: the deal ratified by Westminster and the European Parliament concerns only the general terms of the divorce. The two parties now have until the 31st of December to find an agreement before current regulations will cease to be in place.

As expected, both the UK and the EU have claimed to enter into the negotiation in good faith to reach a comprehensive and satisfactory agreement. However, they both marked clear limits to their willingness to compromise while outlining the main principles of their negotiating strategy.

Michel Barnier, the EU’s chief negotiator, has already presented the 33 page EU memorandum. The document states that the EU aims to reach a “zero tariffs, zero quotas deal” for trade in goods. However, these agreements will be conditional on the maintenance of a long-term level playing field and on the upholding of standards in “areas of state aid, competition, social and employment standards, environment, climate change, and relevant tax matters”. According to the EU, these high standards should be formalised in some sort of legal agreement or treaty.

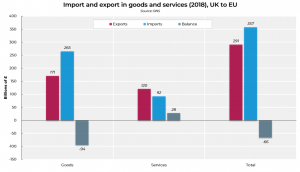

Far more open to interpretation is the area concerning the services and finance industries. In the case of these, the EU did not commit to anything concrete, rather listing a series of sectors that could be covered by a free trade agreement. It is notable that the UK currently runs a trade deficit for goods and a trade surplus for services.

Moreover, Barnier notably confirmed that companies should expect border checks and that there will not be passporting for the banking sector.

UK prime minister Boris Johnson has maintained that the UK is willing to sign a comprehensive free trade deal. He is, however, ready to reduce the scale of his ambitions should satisfactory terms not be reached. As such, he has tried to minimise the relevance of the negotiations, mentioning the countries with whom he intends to start trade talks (the Commonwealth, Australia, Japan and the USA).

Concerning the commitment to a “level playing field”, Johnson reassured the EU around the ‘upholding of standards’, addressing one by one the areas mentioned by the memorandum (except, notably, tax matters). In Johnson’s view, British regulations in these sectors are already more advanced than the ones of most EU countries. Therefore, the UK is reluctant to commit to matching the EU law in any of these areas, as a condition to sign a free trade agreement. This represents a major point of disagreement. In Johnson’s opinion, ‘upholding standards’ doesn’t imply maintaining the same exact regulation and recognising the authority of the ECJ, whereas the EU needs “robust commitments” that UK regulations will not diverge too much.

In addition to that, there are some highly politically charged topics, on which an agreement seems unlikely. First, fishing: the EU demands an agreement to “build on existing reciprocal access conditions [and] quota shares”. Barnier has said that such an agreement is a necessary condition for the EU to enter into a free trade deal with the UK. From his side, Johnson specifically ruled out guaranteeing long term fishing quotas to the EU. The second highly controversial topic is the status of Gibraltar. We believe that a compromise on those two issues is a necessary condition for the negotiations to be successful.

Ultimately, the starting positions of the two parties are some way apart. Fundamentally, there is no commitment from the EU on a free trade agreement in services and a clear disagreement on the two conditions that the EU has laid out if it is to accept a free-trade agreement (fisheries and level playing field). Even though it’s too soon to say that the two positions are irreconcilable, a divorce without any trade agreement is not only possible, it is arguably fairly probable. This situation doesn’t offer much clarity for businesses or financial market participants.

We can probably expect a lot of noise and some fairly difficult negotiations over the next few months, with the market relevance of the issue growing the more we approach the 31st of December deadline without a deal in hand. Where we will end up still remains unclear and that is a cause of concern for financial markets.

What doesn’t help is the fact that both parties have made clear that reaching a deal is not a necessary outcome for them: the threat of leaving the table empty-handed will very likely be posed several times by both parties over the next months and this has the potential to trigger some volatility in financial markets.

For investors, the key issue is the fundamental instability created by the protracted Brexit process. Until a deal is struck and signed off, any planning for the future with regard to UK investments will be subject to a great deal of speculation. Of course, talks between Boris Johnson and EU representatives are fundamental in the economic outcome for the UK, but the daily lives of investors are just as important in dictating how people allocate their funds.

Though the direct hit to individuals’ pockets has not necessarily been felt too deeply in the immediate aftermath of the withdrawal, the long-term effect on personal finance is a concern. Investment has dropped off since the referendum was called and, until some relative stability is reached, we could continue to see the rate of investment drop.

It’s important, in these scenarios, to invest in the long term as opposed to looking for short term gains. It is also a good idea to diversify personal investment portfolios to protect against any additional risk caused by Brexit uncertainty.

News in the UK has been dominated by Brexit since the referendum was called in 2015 and there is a feeling that many people will be relieved to see the issue resolved and consigned to the past. For investors, the sentiment will be similar – relative stability in UK markets after their future becomes more clear will represent far more palatable, fertile grounds for investment.